It was a little like Christmas never came this year, so quick was its approach and so unyielding the regular course of day-to-day life. In years gone by, when the kids were younger and our schedule more relaxed, the tree in our living room drew me into its multicolored glow and stirred the nostalgic remembrance of youth. This year I hardly noticed the tree at all. I was chopping vegetables in the kitchen when I looked up and suddenly noticed it was gone. Danyelle had taken it down and tossed it to the curb while I was out running errands. “You got rid of the tree,” I said, standing behind the kitchen table staring at the newly empty space in the living room. As I was feeling that I’d finally been ready to settle into the holiday spirit and admire our ornamented evergreen for a couple evenings, a flicker of indignation arose, a feeling that was quickly extinguished by the knowledge that I wouldn’t have to help put away the decorations.

I wasn’t alone in thinking Christmas’s arrival and departure were hasty this year. Cartter and Scotty noticed it too. They’ve apparently reached the age at nine and seven respectively when the season is more about the buildup and the time away from school than it is about the actual day of celebration. Naturally, their desire to slow time only accelerates it. During December Scotty asked repeatedly why Christmas was coming so fast, and Cartter said on Christmas Eve that it was “crazy” that Christmas was the following day. Meanwhile, their five-year-old cousin said to me that same night, “Do you know about Christmas? Tomorrow, we’ll wake up, and it will be Christmas! Do you know?” For her, a true believer in Santa Claus, Christmas couldn’t come soon enough, and no doubt, she had passed an eternity waiting for it.

Last year, we had two alleged believers in our house, and this year we’re down to one; however, I suspect Scotty’s belief is less than resolute. He might be growing tired of his role as the family innocent. When he found out I cheated for him in a game of “fishbowl,” pausing the timer while he struggled to explain a word to Danyelle (who was his partner), he sulked and mumbled despondently that he’s “the baby of the family.” His effectiveness in the game was hampered by an ear infection that temporarily crippled his hearing during the first half of the break. When spoken to, he’d most often reply by furrowing his brow and saying too loudly, “What?” Probably aware of being the source of some irritation, he developed a foreigner’s middle-distance stare in moments of trying to intuit what people were saying to him. Between physical illness and despair at his powerlessness, Scotty was left feeling sad: “Why do I feel like I’m going to cry?” he wanted to know the night of Christmas.

Cartter grappled with similar questions. During his time away from school, his propensity for asking “why” was such that I wondered if he were developing a tic. I could hardly speak to him without hearing my words repeated back to me in the form of a question. Finally, I told him, “You’ve got to stop and think for a second before you just blurt out a question.” Sometimes, though, Cartter thinks too much. He developed a profound fear of AI after listening to his Uncle Dominic rant about it replacing humans. Of particular concern to Cartter was the prospect of musicians becoming obsolete, a possibility which caused him to burst into tears at the dinner table. A couple days later, after seeing a 60 Minutes segment about a Boston Dynamics automaton, he called me into his bedroom in a full panic, unable to sleep. He wanted to know why people would build these AI robots. He didn’t want to live in a world full of robots, he said. They would just be these . . . things, and a person wouldn’t be able to make friends with them. When I thought of AI in this childish light, I too found it a little extra frightening.

Throughout Cartter’s and Scotty’s break, I was reminded how difficult it is to be a kid, too old to really believe in Santa, but still too much a baby to comprehend the adult world or one’s place in it. Unaware that the White Elephant game on Christmas Eve was a kind of joke, Cartter became indignant when he opened a scented Jesus candle adorned with the Spanish version of the Lord’s Prayer, more so when he opened a poster of the pink-clad, boy-band-looking “Saja Boys” from the cartoon “K Pop Demon Hunters.” He contained his embarrassment when I quietly explained to him the gifts weren’t serious and that nobody was singling him out. Later, when we reached the final chapter of The House at Pooh Corner, Scotty asked for the title, and I told him it was “Christopher Robin and Pooh Come to an Enchanted Place, and We Leave Them There.” His response was, “But I don’t want to.” Nobody wants to feel left out, like a baby too stupid and innocent to understand the world, but growing up and leaving the enchanted place is a long and sometimes frightening process filled with sadness and loss.

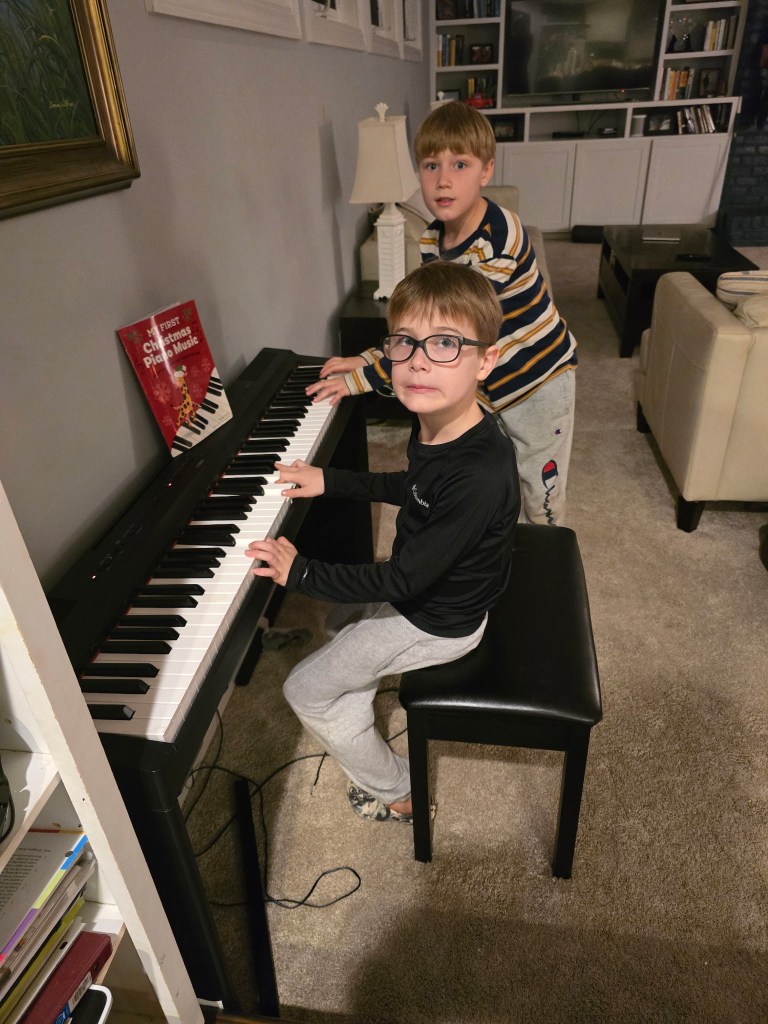

I always think back to being a ninth grader on the final night of Christmas break, sitting on the edge of my bed, staring at my backpack and my swim bag in the middle of the floor. I was so brokenhearted at the impending return to normal that I wept. This year after the kids went to bed on their last night before the return to school, I sat down at the keyboard and played softly one last rendition of Vince Guaraldi’s “O Tannenbaum.” The song is one of my favorites, regardless of the season. I play it at least as well if not better than any other in my repertoire, and I used to listen to it and the rest of the Peanuts Christmas album all throughout the calendar year when I was in my twenties. Scotty seems to have a similar affinity for the Peanuts music.

He was gifted a CD player this year (by both my mother and George, who continued a tradition of inadvertently giving the boys the same thing) along with a small collection of CDs from Mom. His favorite is Charlie Brown’s Holiday Hits. Over the break he listened to it in the kitchen while he drew at the table; he played it while he cleaned his room and while he lay on his stomach reading comics; sometimes, he’d queue up his favorite numbers and just sit still in his little desk chair. He invited me to listen with him too, which I found more than a little flattering. Striking the opening chords of “O Tannenbaum” the night before he and Cartter returned to school, an aching sadness seemed to seep through my fingers and into my treeless living room. It really is cruel how quickly the good times come and go, and it’s somehow hard to believe that we can’t go back and live them again.

Pulling Teeth

At the outset of Christmas break, Cartter was worried about morning swim practices, presumably because he didn’t think I would get him there on time, never mind that I’m the coach, and practice wasn’t going to start without me, or, by proxy, him. The night he called me into his bedroom to express his angst, I told him what was great about morning practice was that we could have family dinner every night, unlike when I get home at 7:30. That’s what I was most excited about, I said. At that Cartter sighed and forgot his concerns about punctuality. “And we can be together,” he said. He said it quietly, almost to himself, and I had to ask to make sure I heard him right. “We can be together,” he said again.

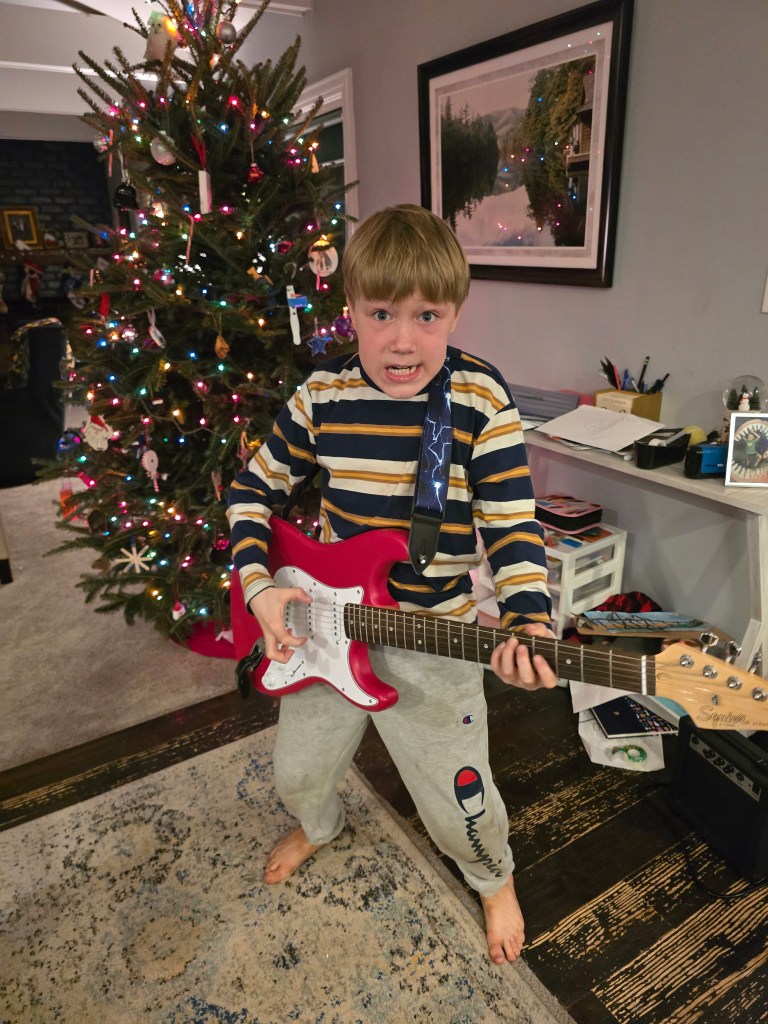

A good portion of the time I spent with the boys during their time off of school was musical in nature. The boys are fully bought in to the notion that they are musicians and that they will grow to be professionals. Cartter asked for a new guitar amp for Christmas, as his old one looked and sounded like it might have been purchased from Kmart, and Scotty asked for a trumpet. I think he got the idea from playing the horn effect on the keyboard in the song “Mr. Big Stuff” at the big concert in December. Anyway, both boys got their wish. Cartter’s new amp looks to me to be very nice. It’s about triple the size of his old one and came with all sorts of built-in effects and wireless capability. Meanwhile, Scotty’s trumpet, while it looks beautiful, is actually a cheap piece of crap, ringing in at around ten percent of the cost of a real brass instrument; nevertheless, Scotty has spent hours upon hours blowing into it. With the help of a beginner’s book and the internet, he’s taught himself how to hold the trumpet, how to stand while holding the trumpet, how to clean and oil the trumpet, and, most importantly, how to produce several different notes with it. He claims he’s going to learn a wide array of different instruments, and for whatever reason, he’s very curious if this will make me angry. “What if I wanna play four instruments?” he asked me. “Would that make you mad?”

Far from being mad, I’m actually very proud of the boys’ resourcefulness and dedication. Even if their methods have sent them into the unholy realm of the internet, the benefit seems worth the risk. I only recently learned that the boys have been using YouTube to give themselves music lessons on their iPad. Danyelle bought the iPad for them some months back so that they could download their school’s app and use it to learn the assigned material, but Cartter and Scotty have discovered that there is boundless treasure that can be easily got at by clicking on the blue circle with the little white lines on it . . . Scotty thinks it’s called . . . “Safari?” Once that application is opened, all one has to do to learn whatever one wants is to, as Cartter would say, “Search it up.”

Together, the boys and I have searched up all sorts of things. Scotty gaped in wonder when I showed Cartter and him a video of a jazz group hearing for the first time Nirvana’s “Heart Shaped Box” and then quickly arranging a virtuosic performance of it. “How do they know it so fast?” he asked. We watched a performance of “Oye Como Va” and Cartter wanted to know if the keyboard player was better than I am. “Dude,” I said, “that guy is playing keyboard for Santana. Yes, he’s better than me.” When we watched a live performance of “Light My Fire,” Cartter was keen to know why Jim Morrison was walking all over the stage and into the crowd acting like a crazy person.

“What’s he doing?” asked Cartter

“He’s just being crazy,” I said.

“Why?” asked Cartter.

“He’s nutty,” I answered. At this point Jim Morrison had descended from the stage and was holding the microphone near his crotch, gesticulating toward some of the young women in the front of the audience.

“Why?” Cartter asked again.

I was out of answers, and it crossed my mind to go ahead and be forthright and tell my nine-year-old, “He’s on LSD,” but I restrained myself.

Besides searching things up on YouTube, the boys and I also spent a good chunk of time playing music together. During one jam session in the den, we even rotated instruments, Cartter and I using guitar and piano, and Scotty piano and trumpet. I taught them a two-chord Latin vamp that is basically Oye Como Va, and another simple chord progression that Taj Mahal uses in the tune “Ain’t Gwine Whistle Dixie Anymo’.” With a little direction, they are amazingly patient with each other. Scotty will pound out chords forever while his brother plays blues minor scale variations on top, and Cartter spaces his lines well and listens for his brother’s tempo.

Wonderful as all this musicality was, my favorite bit of time together was when we finally all went out to dinner. With all the holiday parties and early mornings during the week, and after the trip to New York and then the December swim meet, a month had passed since we went out and sat down at a restaurant. Danyelle and I chose Tony’s Pizza for the occasion, and afterwards we went to the theater and saw the new Sponge Bob movie, which to my surprise was quite entertaining. I liked the way the movie riffed on The Odyssey and how Sponge Bob wanted to be a “big guy,” a fitting theme, I thought, for our Christmas break.

When we got home, Cartter’s loose tooth took center stage. I’d brought Cartter near tears in the morning when I complained of the hassle and expense of having to take him to the dentist every time he refuses to wiggle out a baby tooth. In nine years the only baby tooth of Cartter’s that hasn’t required professional extraction was the one he swallowed with a bite of apple. But that was before we watched Sponge Bob together. After Danyelle went to work on Cartter’s mouth with the forceps she bought off Amazon, big guy Scotty stepped in and deployed what he more or less described as his patented move. Into Cartter’s mouth went his little fingers, twisting the loose tooth sideways and provoking a wide-eyed expression of fear on Cartter’s face. Moments later, Scotty went back in, grabbed the tooth at its base, and, plucking it, pronounced matter-of-factly, “Got it.” I doubt this is what Cartter had in mind when he sighed pleasurably at the prospect of us all “being together.” For him and his brother, growing up in our family is proving to be literally like pulling teeth.

Christmas Pajamas

As is tradition, I was the last to wake up on Christmas morning. Before I came out to the living room where the boys were, as always, tired of waiting on me, I donned the Pikachu pajama top I’ve worn in years past, thinking to alleviate some of the frustration I might encounter with a little humor.

Three years ago, Cartter wrote for his first grade Christmas play that his “favorite holiday tradition” was wearing matching pajamas on Christmas morning with the rest of his family. When I finally emerged onto the Christmas scene this year, I met the boys’ complaints with the joke that they had to go and put on their pajamas before we could open presents. To my surprise, Danyelle informed me, “They can’t.”

“Why not?” I said.

“They’re too big. Their pajamas don’t fit anymore.” Not only do the silly Christmas pajamas no longer fit. The boys, who now sleep in boxer briefs, don’t own any pajamas at all.

A Father’s Love

We were riding back from the beach on New Year’s when Scotty asked me from the back seat, “Daddy? Will you always love us?”

I was surprised at the question, and after searching around for the correct words, I came up with this: “My love for you and Cartter is indestructible.”

Cartter added helpfully, “And for Mommy,” which made me and Danyelle both chuckle, but Scotty said dubiously, “Are you sure?” and “Sometimes it seems like your love is . . . destructible.”

“What do you mean?” I said pulling up to the red light at Bowman Road. “When?”

“Like . . . when you get mad,” said Scotty, “and you yell at us,” an accusation to which I might have blurted out “What in the fuck are you talking about!!!!” but which I instead endured with only minor protestation.

Maybe Scotty was doubting the steadfastness of my love after observing my father call us all “idiosos” at the beach house earlier in the day. Along with my sister, the four of us took the mile walk down the beach to the throng of “polar bear plungers,” whom we joined in stripping to our bathing suits and racing into the frigid waters, leaving Dad with his wife, his champagne, and his much less interesting house guests. Clearly jealous (and drunk), Dad peppered us with insults upon our return. Could it be that Scotty saw my father’s behavior as evidence of what’s to come?

Or maybe in his apparent attempt to knock me off balance with his line of questioning, Scotty was modeling his behavior after my response to my father’s taunts. Danyelle and the boys and I sat eating in the den while Dad entertained in the dining room, and at one point a guest came in trying to locate a trophy about which Dad was bragging. He explained to me that it was a “hiking trophy” that Dad won when he was fifteen and asked if I knew where it was. “It’s right there on the bookshelf!” came Dad’s booming voice from across the kitchen. I pointed to the gold cup tucked in one of the shelves and commented to the guest that it was strange that Dad would have been given such an award at fifteen and that he would still have it. Then, I got the idea to look around for some of my old awards.

To my great not surprise, I found that my room had been ridded of all my former glories. Trophies, medals, ribbons, and pictures had all been removed in one of George and Dad’s desperate hurries to purge the house of anything that recalls the before times, when Mom and Dad lived there together with their children. I did manage to locate a slew of ancient board games gathering dust, as well as Christmas ornaments not used in decades. It was much less important to be free of these items. Ditto the three-tiered wrestling trophy from 1968, which I found in the guest room closet. Immediately, I knew what to do with this piece of treasure.

When I first placed the trophy on the dining room table in front of where Dad sat holding court, his face was one of annoyance, maybe because I was handling a precious keepsake, maybe because he was embarrassed by his own pride, definitely because I was making fun of him. Trying to deflect, he brought up how another guest’s two brothers were state wrestling champions in Colorado.

“It’s not too late for me to have a brother,” I said, which quieted the room. Dad and George’s two female friends tried wrap their heads around what I was insinuating. They looked at me as they tried to piece it together, surely believing that I was referring to the possibility of Dad impregnating someone, perhaps thinking that that someone would have to be someone other than his postmenopausal wife. My sister was the only one who got it.

“Right,” she said, standing back from the counter where she’d been munching on the cheese spread. “Because I could become a man.”

“Exactly,” I said nonchalantly, pausing to let it sink in around the room. “And then I could become a woman.”

Betsey and I both laughed, and Dad’s ultimate response was, “See you in 2027.”

Miscellaneous

It’s worth noting that both kids went fully in the water at the plunge. They ran in three times with me, and each of us dove in between four and six times. Quite likely, fatigue and hunger put Scotty in a foul mood later in the day, and that’s why he was harassing me about my love being “destructible.” He suffered hunger pangs around dinner time but refused to eat anything, instead opting to sequester himself between the stools at the kitchen table. He inspired from me an impromptu song on the keyboard whose refrain was “Used to be a man on the beach . . . Turned back into a baby.”

“Am I a baby?” he asked at one point. Once his mother made him waffles, eggs, and sausage for dinner, he was fully restored and stomped around the house declaring that he was Snoop Dogg.

That night I enjoyed playing for the boys a video of Mr. Rogers singing a song in which he relates to kids’ incessant desire to ask questions. “Why why why why why why why,” he sings, “Why why why I wonder why?” Cartter and Scotty sat rapt, occasionally glancing at me unable to suppress a little smile of acknowledgement that yes, he was singing about and directly to them.

I’ve discovered a chore that the kids can help out with: emptying the dishwasher. I put Scotty on silverware duty, and he asked, “Do we really have to do this?” I wondered about his dirty mits on gripping the fork tines and the spoons, but the answer was a resounding yes.

Danyelle’s friend Mary Frances stopped by for a visit during her time in town from Florida. She has a ten-month-old, and after it napped on her for forty-five minutes, it awoke in a foul mood. Watching MF scramble to get her things together while being pummeled with the baby’s cries was like being able to see the inner workings of her endocrine system. “Triggering, isn’t it?” I said. Again, a resounding yes.

The boys have turned into avid football fans over the last few months. Dad expressed his dissatisfaction about them not being involved in team sports while we were at his house on New Year’s (because of course their participation in swim is cause for some concern), but the fact is they spend hours each week in the neighbors’ yards playing tackle football (which is no doubt much more of a health risk). Cartter about had a panic attack when he thought he was going to miss the semifinal game between Ohio State and Miami, and both boys are very keen to know who I want to win in both the semifinal matchups. Cartter is starting to know the players on the different teams both by name and number.

Both the boys said around Christmas time that their favorite part of the break was the night they rode around in the golf cart with me looking at all the lights in the neighborhood. Cartter was eager to learn about the tastefulness of the various decoration schemes, asking me about many of the houses if I liked them or if I thought they were “too much.”

Sammy’s limp is getting significantly worse. It’s to the point that she barely puts any weight on her leg, calling to mind the vet’s words at her last visit: “Well, it’s good that she’s putting weight on it; that means we don’t have to cut it off.”

I came home one day to find her alone in the house, very excited, hopping around on her bum wheel with her tongue lolling, trying to tell me something. Feeling eager to please, I loaded her up in the golf cart. She’s growing fonder all the time of riding in the cart and will even sit down with her haunches on the floor now instead of nervously standing with her back paws dangerously close to the edge. On this occasion, she was much too worked up to sit down, though. We eventually parked at the tennis courts after I decided against swimming her at the boat landing (As much as she loves to swim, her arthritis has gotten to the point that after a few trips out into the creek, she cries on the swim back to shore with her ball in her mouth). When we disembarked and headed out toward the playground, she was elated, and I realized what she had been trying to tell me with her excited bouncing at the house: Danyelle and the kids were in the park.

Seeing her joy at being reunited with the family, I remembered when she was four-months-old, and Danyelle and I left her at the kennel for a night so that we could go to the Clemson-Oklahoma game in the Orange Bowl. It was the first night we ever left her, and one of the few nights in her life that she’s spent away from us. She was a frequent visitor to the veterinary clinic attached to the kennel, and the young female vet and her techs doted on her and called her “Sammy Wammy.” The day after the Orange Bowl, Danyelle and I sat in the waiting area while one of the young techs went to retrieve her for us. I heard her bursting out of her cage and her claws clicking and sliding across the hard, smooth floor before she came into view. She stood stiffly on the other side of an open doorway, bristling with energy from her nose to the tip of her tail. She looked first straight ahead, then to her left, and then finally to her right, where Danyelle and I were sitting. Then, she barreled toward us and leaped for us, paws up, her whole body wagging.

I cherish those exuberant greetings. They’re fewer and farther between these days. Sammy spends a lot more time napping below my feet now. She’s currently doing just that underneath my desk while I write these words. She likes to cozy up under my stool in the kitchen while I eat and to rest her chin on its little cross support between the stool’s legs. She also squishes herself underneath the piano while I play Vince Guaraldi tunes, often lying on top of my feet while she does so. She chose this spot when Scotty started blowing on his trumpet on Christmas morning, an event which set her whole body to trembling with fear.

My mom said once that it’s not about how much time she has left but the quality of that time, and I agree with her more than ever. I wonder if the reason her limp is so bad lately is because Cartter has been home. Whereas Danyelle and I largely ignore Sammy when she starts grabbing toys out of her bin and running around the dining room table with them in her mouth, Cartter is much more inclined to indulge her, sending her into bounding, sliding hysterics as she chases thrown toys and runs from her entertainer. I know it’s not helping Sammy’s arthritis, that it’s probably worsening her pain, but I don’t tell Cartter to stop. There’s only so much joy left for the two of them together.

Finally, Poppin died the day after Christmas. I’m sure the reality that he’s gone will set in over the course of the coming years. I talked to Grandmom a few days after it happened. She said she missed him. I told her about how life seems so much busier now that the kids are getting older, how even though sometimes I look forward to being less busy, I’m sure I’ll look back on these times the way I look back and miss the boys’ toddler years now. She told me about when Poppin was at college and when he enlisted in the Marines. She told me about how poor he’d started out and how he didn’t care too much about money. I heard her getting sad, and I told her about the kids’ swimming and their music and their neighborhood exploits. Ultimately, it felt like the best I had to offer – stories about the boys and all the funny things they do.