Pace sets are as much an exercise in belief as they are an exact science. During my final two short course seasons as a swimmer, I tried to convince myself that the 2:06 200 breaststroke pace I practiced would manifest in a competition, but when meet day arrived, I never went under 2:10. A 13-year-old girl whom I now coach recently put into words the thought I so often tried to bury back in those days when I was in practice splitting the 32.5s I needed to make my goal time: “I think that’s not realistic,” she said. She’d just finished a pace set for the 1,000, cruising to a 1:10 on the last 100; she’d looked like she was swimming warm-up, but to her mind, holding that speed for eleven-and-a-half minutes was impossible.

“Well, I believe that’s true,” I told her, “but it’s also wrong.”

She’s a hard case – talented and even more full of self-doubt than the average age group swimmer, the same kid who told me she couldn’t control her thoughts because her brain “has a mind of its own.” There’s no reasoning with her; the only way I see to teach her what she’s capable of is to pummel her with aerobic intensity, but she has a nagging shoulder issue that always seems to crop up right when we’re on the verge of a breakthrough in her training. As I write this, she’s getting on the bus with the team and heading upstate to Greenville, where she’ll be swimming the 1,000 tonight. I’m sure she’s very nervous. I’m also sure that she won’t hold 1:10s. When she starts to get uncomfortable in the early portions of the race, she’ll back off. She doesn’t believe she can do it.

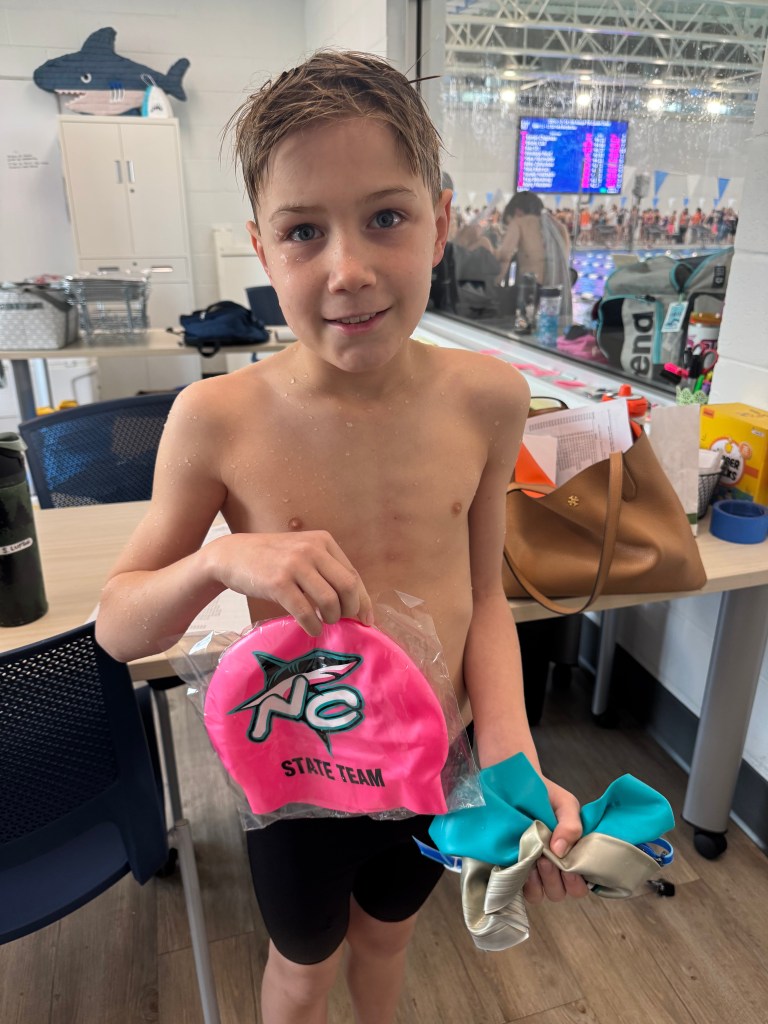

My nine-year-old son has a similar way of talking himself down. “It’s not like I’m gonna be able to swim in college,” he said on the eve of his first big competition. He was nervous and trying to rationalize his anxiety away by telling himself he’s really not that good, therefore a poor performance wouldn’t be that consequential.

I talk to myself the same way about my potential longevity as a coach sometimes. “I’m not going to do this forever,” I’ll say, or “Five years is too far out to project.” I see the bad bosses, the problem parents, the rival programs competing for talent, and I’m like my son, my 13-year-old swimmer, and my former self: I consider the possibility of my perseverance and think, “That’s not realistic.” In the past I’ve proven myself right. I lasted four years in my first stint as a year-round coach before bolting, then three years in my second. I’m entering my third year in this latest go-round, and the usual sources of frustration are as abundant as ever, hence my sometimes-negative outlook. The biggest difference this time is my kids. Their involvement in swimming is a governor on my own, and it’s a check on the desire to cave to my darker emotions and walk away.

There was a time in my coaching career when I would have been on the bus headed to Greenville, full of false hope that I could change that 13-year-old’s way of thinking rather than accepting that she has to learn the hard way. Now, I know I can’t force her to do her best and that she’ll be fine without me. Better to stay home with my kids. There’s another meet in town next weekend that they’ll swim in and that I’ll have to attend, and if I’m not going to burn out on coaching again, I can’t be overly involved in every one of my athletes’ races. I want to stick around for Cartter and Scotty as long as I can. Seeing them flourish around the pool makes bad bosses and parents worth suffering.

I have a younger group right now that’s starting to come together. Over the last three months, they’ve learned a bevy of drills, and they’re starting to be able to run through them while staying on an interval. There are few things more gratifying as an age group coach than seeing three to four lanes full of kids moving up and down the pool as a unit, especially when one of those kids is your nine-year-old son. He’s a lynchpin for the group, not the fastest or the most talented, but the type of swimmer who makes practice better for everyone. I had to excuse myself to the other kids for leaning on him so much to demonstrate new drills. “Me and Cartter planned this one together,” I told them. “He said he thought everyone was probably going to be confused and mess up.” Usually, that would have been the case, but after he showed everyone how to perform the skill, a complicated freestyle switching drill, the group had no problem with it. Of course, once I moved him over into a lane with the older boys, a soon-to-be eleven-year-old wouldn’t stop talking to him while they were on the wall, and Cartter started flubbing the drill himself.

Everyone wants to be Cartter’s friend at the pool. He shows his toothy bashful smile all the time and is comfortable with himself in a way I know he isn’t at school. Having him around is like being able to swim a race with one eye on the pace clock all the time. I see him and his brother improving and making friends; I see their growing pride in their sport and their team; and when I imagine staying on deck the next five years and putting up with all the nonsense, I think, “Maybe it isn’t so unrealistic.”

Not Friends

The boys are suffering their first breakup, or rather Cartter is; Scotty, as Danyelle puts it, “doesn’t give a fuck.” The other party to the separation isn’t a romantic interest but a friend, one who was Cartter and Scotty’s first ever sleepover host, a child who has spent an inordinate amount of time at our house over the last two years. The boy’s father called the cops on our neighbor across the street, and his kid’s no longer a welcome guest, a condition to which Cartter and Scotty have each responded differently.

The debacle started when Danyelle and I were sitting in the den with our friend Dan, who was in town visiting for the weekend. It was a Sunday afternoon, the fall sunlight was slanting in through the shutters, and the three of us were lounging, a tad hungover from the night before, while the boys played outside. I’d just put on my blue light blockers with the black frames and rose-colored lenses and was reaching for my laptop to show Dan something I’d been working on when I heard a high-pitched, percussive sound from outside. It was like the sound of a woodpecker slamming its beak repeatedly into a tree trunk, except it was a human voice. “Do you hear that?” I said, and then, dread involuntarily creeping into my voice, “Is that Jeanette?” It was. Our neighbor across the street had been peering out her window, and upon witnessing the boys’ friend throw a football at her son, she stormed out her front door and into our next-door neighbor’s yard, where she unleashed a tirade of fury upon the child. Among some of the best lines were, “You better watch out! I’m from New York!” “I will come for you and your family!” and, directed at my boys, “Say he’s a bad friend! Say it!”

Normally, this outburst would have more than exceeded the daily quota for crazy, but the situation sadly escalated from there. The neighborhood gossip queens just so happened to ride by on their bicycles at that moment, and they called up the boy’s father, who, rather than come over himself, called the police, an act that was aptly summed up by an acquaintance of mine as “a bitch move.” He proceeded to stomp up and down the street talking to everyone except Jeanette and to whine incessantly to the police, presumably unsatisfied that his son’s offender had not been taken away in handcuffs. Since then, he’s refused to let the matter go, asking Danyelle and me to provide a written statement, and, when we declined, blocking us on his phone. He passed by Danyelle walking the neighborhood and pretended not to know her. Again, his son’s no longer a welcome house guest.

Cartter, despite his best effort, has failed at concealing his hurt feelings. The weekend after the police were called, I could sense the exact moments when the habitual impulse to ask, “Can we see what Bennett’s doing?” crossed his mind. Our gaze would meet; I’d ask him if he was okay; and his eyes would fill with tears. He cried at the kitchen table; he cried on a dog walk with Scotty and me; and he cried in the back seat of the van riding to the grocery store. He’s asked in various ways why the adults involved have caused this horrible rift to happen, and I’ve told him that Jeanette is “not a real adult” and that Bennett’s father is apparently a troubled individual. It’s obvious that Cartter can hardly believe the consequences. We saw Bennett at the neighborhood tennis club on Sunday evening; he was tearing through the beach volleyball court throwing sand at his little sister while his mother stood idly by, presumably numb to the boy’s mischief. Cartter expected to run up to his friend and play, and when we told him no and kept on walking, it brought on a fresh round of hurt and questions.

Scotty has had a much easier time of seeing the upside to the whole falling out. After all, he has lots of other friends, and Bennett certainly wasn’t the nicest one. Whereas Cartter says that he continues to replay in his mind Jeanette’s screaming episode and the immediate aftermath during which the three boys holed up in Cartter’s room, Scotty says simply, “I’m over it.” The weekend following the blow-up, while Cartter was at a sleepover with a school friend, Scotty was left alone with Danyelle and me, a rarity that occasioned both reflection and celebration.

Our night of being a trio coincided with my old coaching colleague and drinking buddy Will Bayles being in town for a visit, and once Cartter was deposited at the friend’s house, Scotty and Danyelle came to pick me up from the bar. I climbed into the backseat of the Rav to be next to my youngest son, and he even let me hold his hand while we drove over the bridge. “This almost never happens,” I mused. “I think I get to spend more time alone with Scotty than I get to spend with the just two of you,” and then I thought out loud, “One day when Cartter goes away, it will be like this for a while.”

I asked Scotty what he thought, and he said, “That would be bad . . . because Cartter would be gone.”

Despite this grim assessment, Scotty had a wonderful evening that included a trip to Kickin Chicken, a dance party featuring Horace Silver and Stanley Turrentine, and a hard-fought game of charades. I was enthusiastic about all of it, and Scotty asked his mother the next morning, “Why was Daddy so much fun last night?” I suspect he’s catching on that I’m a better date when I have plenty of beer.

But Mostly Vegetarians

Another Thanksgiving play at Porter-Gaud, and another Lupton boy was broccoli. Scotty purportedly tried to secure a larger role in the play, but when things didn’t break his way, he was pleased to play the part of cruciferous vegetable like his brother before him, and to deliver his line, “Yes, but mostly vegetarians” with a slight smirk and a wag of his finger. The lights reflected off his glasses, and the poofy green hat swallowed up a good portion of his face. He, of course, performed with a workmanlike attention to detail and without any sign of the self-consciousness that plagued Cartter on stage during the song and dance numbers.

There were some poignant moments when I thought to myself, “I can’t believe it’s actually been two full years since I saw this show,” and my eyes welled up at the knowledge that there are no do-overs after Scotty – every phase my sweet seven-year-old passes through is a phase that is gone forever; mostly, though, I longed for the production to hurry up and end.

Scotty’s line was right at the beginning, and after he delivered it, a giant with a staggeringly broad head and neck sat in front of me, leaning this way and that to point his expensive camera at his cheesing offspring on stage. The man successfully blotted out about half the stage.

I could still catch occasional glimpses of Scotty standing in the back row of a set of bleachers. He was next to a tall boy whose “truck driver” costume entailed a ball cap with a long-haired wig. The hair swished back and forth as the truck driver sang loudly and gesticulated wildly, displaying great excess of enthusiasm for a “hip hop” Thanksgiving song with the words “Gobble-Gobble. Gobble-Gobble-Gobble-Yo!” Even if this oversized child hadn’t been jostling Scotty and nearly knocking him off the top of the bleachers, I imagine I still would have found myself wishing I could karate kick him in the chest with impunity, or perhaps deliver a paintball to his face – something that would leave him breathless and gasping in panic. Scotty told me afterwards he is not friends with the boy, whose name is Jackson. Relieved, I let it slip that Jackson seemed like “a real fucking asshole.”

Maybe my favorite part of the show happened before the curtain even lifted for the opening number. A screen displayed cards on which the students had written and drawn what they were thankful for. Two years ago, Cartter expressed his thanks for the Earth, because “without it we would all die. Also there would be no life.” Sitting between his mother and me, playing hooky from school to watch his brother’s play for the second day in a row (the second graders performed for the whole lower school the day prior), Cartter correctly predicted that some kids in Scotty’s grade would also be thankful for the Earth. Apparently, the Earth was one of the suggested objects of thanks, along with “family,” “friends,” and “pets.”

Safe to say Scotty’s choice did not come from the list of suggestions. He was the only child to give thanks for “cows and chickens, because without them we would not have chicken, eggs, anything that contains milk, and no cow meat.” To accompany this statement of reverence for livestock, Scotty drew a scene from a barn. A cow-like animal stood in front of a table stacked with milk bottles. Less prominently but perhaps more impressively, a chicken squatted in the corner above a pile of eggs, a dialogue balloon near its beak with the words, “Just one more!” I imagined this chicken was persevering through considerable strain, and I had a much better sense of Scotty’s true appreciation for eggs, chicken fingers, and cheeseburgers.