In the six years I spent as a summer league head coach, I never did an awards banquet. My teams had a pizza party at the end of the season, and I would stand up and congratulate all the kids and say thank you to the volunteers. It’s not that I don’t like recognizing individual kids in front of the group; I try to do that as much as possible throughout the season, both for their efforts in practice and at meets. A kid masters a new skill, I announce it; someone has a great race, I let everyone know. By season’s end, everyone has been recognized a lot and has plenty to feel good about. In my experience, that’s what works. Passing out silly certificates for things like “Coach’s Award” doesn’t. It detracts from the winners’ real accomplishments, and for the kids who get snubbed, it robs the good feelings they earned during the season. That’s what happened at my kids’ summer team banquet this year. The coach gathered up all the children from the pool and had them sit in rapt attention as she called the chosen ones up one at a time to receive a certificate and have their picture taken. About half were called. My two boys were not.

“I mean I can see how my kids could get overlooked. On swim team. At Creekside,” I said to my neighbor friend George. We were finishing a beer in the parking lot outside the pool gate. George and I had been talking about myriad topics from the Braves to the recent Jeffrey Epstein “no client list” news, to George’s twelve-year-old’s haircut. “Looks like you could use a haircut,” I said to the boy. His hair hangs in his eyes, and it drives his father nuts.

“Well, I don’t want a haircut like that,” he said motioning to his father.

I looked at George’s perfectly average hairstyle, parted to one side. “I don’t know,” I said. “Looks alright to me.”

“That’s, like, a forty-year-old man haircut.”

“Right, you wouldn’t wanna look too manly.”

George offered a genuine thanks when his boy walked away. Then, he imitated him waking up from a nightmare about our conversation. Having a beer with George was the main reason I wanted to come to the banquet. When I made the crack about seeing how my boys could be easily overlooked, he pondered it a moment, and said, “No, I don’t see that at all.”

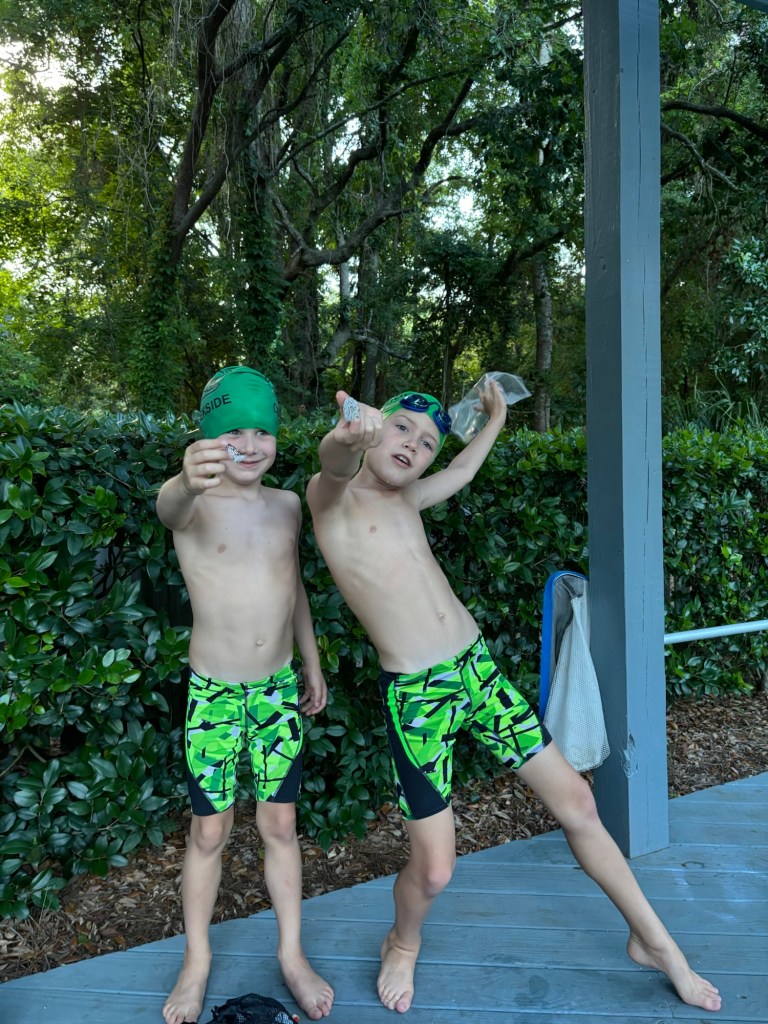

Part of the reason my boys are so difficult to miss at Creekside is that I coached the team for three years: I still manage the timing system at the home meets, and I know nearly all the families. They know me too. But even absent my role with the team and the attention that it no doubt confers upon my sons, Cartter and Scotty were undeniably standouts in the 7-8 boys division this year. Their practice attendance wasn’t perfect, but they had to have been at least in the upper third; they competed in every meet including the championship meet; and they were point scoring machines. Cartter was the high-point winner for the team at the championship meet and was probably the team’s leading point getter for the entire season. He set three individual team records and was part of two team-record-setting relays. These are the types of things I might have mentioned along the way as a coach. In terms of positive feedback, they’re what one might call layups. Meanwhile, his little brother Scotty, who turned seven in April completed a legal twenty-five butterfly for the first time ever this summer. He even swam butterfly at the championship meet. That neither child got any shout-outs for these accomplishment strikes me as either lazy, stupid, or mean-spirited. I’m hoping it’s one of the first two, but regardless, it’s irresponsible. I’d say that would be a fair characterization of our summer team coach’s approach in general: irresponsible.

One thing coach did do was print a bunch of ribbon labels. Cartter and Scotty each came away with a fistful of ribbons, which they argued over back at the house when the banquet was done. I was playing the piano in the living room, and they were sorting ribbons on the bench in front of the picture window, one of them telling the other he hadn’t won any first places or some such silliness. I stopped playing and told them that I didn’t think Michael Phelps argued with anyone about the gold medals he won. Rather, he goes around telling people what he did to win them, and people are so interested that they pay him to do it. I said he probably even lets people hold his medals and try them on and have their picture taken. That shut them up.

They’d had no idea there would be awards or ribbons at the banquet beforehand. They hadn’t even wanted to go at all, preferring to stay home and learn how to play hearts at the kitchen table with their mother and me. I was the one who insisted. After two weeks of spending all my free time poring over swim resources, taking notes, and parsing all my ideas into annual, monthly, and weekly training cycles for the start of the upcoming year-round season, I needed to socialize. On our way to the pool, we passed a neighbor walking his dog, and I stopped to congratulate him on his oldest leaving the house for college. We were in the golf cart, and the boys didn’t notice when our neighbor motioned to them, indicating that when they get older, the separation will be as hard for them as it will be for us. “Well, we’re soaking it all in,” I told him. “We just played some hearts, and now we’re going to the swim team party.”

“That’s a good day,” he said.

An array of medals adorned a table near the pool entrance when we walked through the gate, but even with the promise of a shiny prize glinting in their eyes, the boys’ priorities remained elsewhere as the party got underway. Shortly before the awards show broke out, they made a small, curious scene. After they jumped in for a swim, they laid out a towel in front of the raised wooden deck where people congregate, at the end of the narrow walkway from the front gate. Then, they got down on their knees facing each other, closed their eyes, bowed their heads, and clasped their hands in silent prayer. Danyelle and I tried not to look at them too much while we kept on talking to George and his wife. Of course, we failed. It was impossible not to stare, to wonder what the hell they were doing, and to be embarrassed by whatever it was. After a minute, they were lying face down with their heads on a folded-up towel as if they had suddenly converted to Islam. We later learned they were praying for the pizza to show up. Apparently, hunger drove them to religion.

When they finally got their pizza, somehow eluded recognition from their coach, and collected their fistfuls of ribbons, they were eager to get back home. I told them they could go on ahead of Danyelle and me, and they scurried off the deck and out the gate while we finished talking with our friends. We found them maybe forty-five minutes later in our living room. It was getting dark outside, but they had not turned on any of the lights. “What took you so long?” they wanted to know. “It took you forever!” I’m sure they were starting to get nervous. They still sleep with stuffed animals. They pile some up at the foot of their beds and some near their heads. Then they take care to cover them all up with the blanket so that everyone will be safe in the night. Cartter especially is afraid of the dark.

Part of me is glad they got snubbed by their summer league coach. They’re better than summer league awards. I’ll be coaching their year-round groups in the fall, and they’ll be recognized for their effort just like their teammates. I have their training plan mapped out already. They’re going to learn a lot, and there won’t be any phony awards for them to not win.