As the final pair painstakingly made its way around the last holes late Sunday at the Masters, the empty fairways were a sad sight. Not long before, they glistened with dew in the morning sunlight; players strode down their centers after blistering drives; and patrons stood scattered around their edges admiring the spectacle. Then, there were no wrong turns; the golf was everywhere; and life was a wandering picnic of pimiento cheese and egg salad sandwiches. In the fading light on Sunday, though, with only a handful of players remaining, and the once scattered crowds congealed into a throng around the eighteenth green straining to get a look at the final decisive action, the earlier holes were left in picturesque emptiness. Making my way up eighteen fairway into the horde, part of me wanted to head over to number ten and walk down the left side pretending I was twenty-three years old again, a vodka lemonade from the clubhouse in hand, heading back out on the course midday Friday before any of the players were cut. Those were carefree times. Of course, I didn’t heed the impulse. Nobody wants to stand alone in an abandoned part of the course and feel left behind when the last putt drops.

Nowadays, a trip to Augusta at Masters time means leaving my two young sons at home in Charleston in the care of my mother. I could write all about the golf Danyelle and I saw while we were gone, about the daily bets, the strange digs that were this year’s lodgings, but it’s much more urgent to me that I document the two boys that we left behind.

As I write these words on our first full day back in town, it is my younger son Scotty’s seventh birthday. Scotty shares my nostalgic inclinations, and he has mixed emotions about the occasion. He told me three weeks ago when he was still six, “I wanna stay this age.” No doubt Scotty would prefer a Thursday badge and a lemonade to a choice spot around the green on Sunday. Like I am, he is loath to see the world in a hurry to reach a conclusion, an outlook that is particularly evident in light of its contrast with his big brother’s.

Cartter is a Sunday badger all the way, outcome-driven, always looking ahead to the promise land. Unlike Scotty, he can’t wait to get through the helpless, childish phase of his life; he longs for the greater autonomy he imagines comes with maturity. “I’d give school a three” he explains to Scotty in the backseat of the van, dismayed at little brother’s more ambivalent rating of five out of ten (“I kind of like school, and I kind of don’t,” says Scotty).

Part of Cartter’s beef with school is that it’s increasingly competitive. Class rank is becoming more and more apparent, and even though he may not entirely like all the competition he sees going on around him, Cartter is eager to get ahead. He’s a driven little creature. Emerging victorious in the friends and family March Madness bracket challenge is so important to him that his team losing is occasion for outbursts of rage and possibly tears. He’s a star pupil at swim practice and is intrigued by the idea of travelling for a year-round meet. “Not maybe,” he says when I suggest trying it out next year, “Definitely.” He enjoys rearranging the pieces at the end of a chess match so as to continue, almost like he’s doing drills. Life is a race run by the rules for Cartter. When I explain to him at the end of a basketball game that one team is fouling on purpose to stop the clock, his response is, “So they’re cheating.”

Scotty is quite the opposite when it comes to this competitive nature. He cares not a whit about March Madness picks, but enjoys the chance to chant at the TV when so moved by the group’s rooting interest. When confronted with the idea of a travel swim meet, he’s downright appalled: “I don’t wanna spend my weekend that way,” he says. And when it comes to chess, his chief interest seems to be the pieces themselves, which he moves around without heeding the rules of the game and which he tends to handle a little too loosely for my taste. While he got top marks in fifty-three out of fifty-four categories scored on his most recent report card, his P.E. teacher deemed him merely satisfactory in the area of “knowledge of movement concepts, game tactics and strategies.”

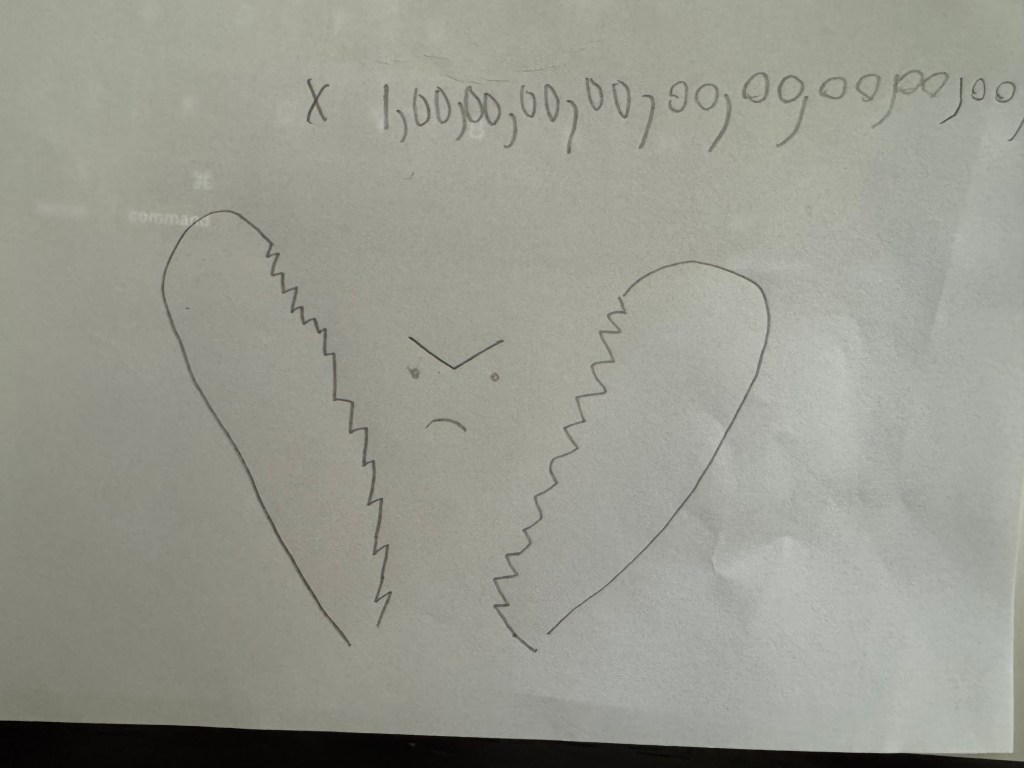

Appreciating a more relaxed pace absent the constant urge to get ahead might seem a blessing, but it’s not without its problems. For one, a person can’t resist the passage of time. I can never be twenty-three with a vodka lemonade on the left side of Camelia again, and neither can Scotty go back to being six, much to his grumpy depression. “This is the worst birthday yet,” he said in a fit of moping back and forth through the house, brow furrowed, arms hanging stiffly at his sides. He claims he’d rather be six than seven and that being five would be “even better.” Going back to the time when he was suspended in his mother’s womb would be better still, but retreating all the way to non-existence would be “not so good.” Time’s stubborn procession has seen Scotty spend part of his birthday brooding in silence and delivering pictures of broken hearts with surly faces drawn between the jagged edges.

Besides being ushered along unwillingly in time’s ceaseless march, the tendency to want to hang back can often leave a person feeling left behind. Standing alone in a deserted part of the course when McIlroy drains a birdie putt on eighteen in a playoff is a sad place to be. So too is idling in pseudo-babydom while your beloved older brother races toward adolescence. Danyelle and I were both disturbed at Scotty’s reaction to Cartter’s first ever sleepover without him recently. He seemed to want to enact his brother’s presence by engaging me on the driveway basketball hoop, an effort which ended with him seated on the ground pouting and unresponsive for about ten minutes. He later made a confusing attempt at a game of hide-and-seek and disappeared into the pantry at bedtime. Being left behind by his brother for a night was apparently enough to temporarily break Scotty’s brain.

Of course, rushing to stay ahead does nothing to prevent a person ultimately feeling left behind either. It might even make the sting worse. After Danyelle and I were gone four days for the Masters, Cartter was the one to complain about being left. “You were gone for so long,” he said. “Don’t do that again.” And at the conclusion of a trip that I’d long looked forward to, I was disturbed by the thought of the empty fairways that lie ahead. “You guys are never allowed to leave,” I told the boys on a walk. Cartter mentioned college, and I said, “I don’t know. You can go to college, but you have to live with us forever.”

Miscellaneous

Among the many injustices of Scotty’s aging, he got a prescription for glasses on his birthday. The boys missed school on our first full day home so that they could get their eyes checked. Scotty’s none too happy about the diagnosis. “I don’t wanna be a nerdy kid,” he said when he learned of the possibility a few weeks back.

Favorite conversation from this year’s trip to Augusta goes to a discussion with the Sheehans on the top of sixteen about recurring dreams. Included were desperate discoveries of underwater breathing capabilities, disappearing clothing, and the terror of walking to eighteen tee leading the tournament and knowing that one is about to be exposed for the fraud that he is.

Of all the empty fairway moments to come when the kids finally do move away, I suspect some of the most brutal will be the ones in their abandoned bedrooms. Cartter calling us back into his room after bedtime has become so routine that it ceases to be annoying, and lately he even gives genuine hugs, holding on tightly for a moment after his mother and I start to release. Scotty likes to settle into his night with a little back rub; it is amazingly easy and gratifying to press the tension out of his back with my hands and see him melt into his mattress. In years past, he would bounce on the bed while he slurred the words “night night, I love you, see you in the morning, see you for breakfast, xiexie (Chinese for “thank you”)” into three or four rapid syllables. We still exchange the nightly parting blurb, but now, instead of bouncing, he calmly stops me for a question before I leave. “Daddy,” he asks, “What are we going to do this Friday?” A week or so ago he asked me, “Can you guess what my favorite state is?” I got it on the fourth try: Nebraska. A couple weeks before that he asked, “What does swimming help you with?” I said swimming, and he followed up with, “Why do people wanna be sumo wrestlers?”

On the eve of Scotty’s birthday, Cartter pulled out the acoustic guitar that my father gave me when I was eleven. I never learned to play it. It lives in the guest bedroom closet. Cartter claims to know how to play a C chord and an A minor chord, but I don’t know if he’s telling the truth, because the guitar has never been tuned, and I’m too lazy to look up the fingering online. Cartter laid the instrument down on the floor in Scotty’s room, strumming and singing a song, most of whose words were, “Scotty” and “I love you.” He wrote his composition down, chord symbols and all, titling it “Scott Scott” and including instructions for his brother to “practice it.” I try to imagine Scotty in his room, singing over a nonsense harmony about how he loves himself.