As I pointed at each little pair of dots in the picture next to the table of contents, my 6-year-old Scotty peered over my shoulder, and I asked him, “Can you tell what those are?” A dog lay next to a campfire, looking out into the surrounding wilderness.

“Stars,” said Scotty. It’s what I’d thought at first too.

“Are you sure?” I prompted him. “Look again.”

He stared more intently, and said, “Or are they eyes?”

“And beyond that fire,” the caption read, “Buck could see many gleaming coals, two by two, always two by two.”

I like to take a little bit of time between each read aloud book that the kids and I do, to let each one digest, to make sure we’re ready to commit to something new. It’s been a few weeks since we finished The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, and when Scotty started perusing the titles lying on the table next to me, I figured it might be time to get started on our next literary endeavor. After quickly scanning and discarding each of the books in my stack, Scotty landed on one I’d selected for him and his brother, a paperback with a howling wolf on its cover. He skimmed the pages looking for pictures, gleaning what he could about the text from them, and the first thing he asked was, “Who’s the guy?”

I loved the way he asked it. It wasn’t just that he couldn’t read the author’s name, which graced the cover in cursive letters; from his tone I inferred a deeper question: “Who are we going to be listening to if we read this book?”

“Jack London,” I told him. Then, remembering the first time I tried to read the story to his older brother Cartter, when he ran from the room and hid, crying beneath his covers before we finished the first two chapters, I added, “It’s sad. The dog gets beaten.”

It was the end of the first day of the year, and we’d spent it on Sullivan’s Island as is our tradition. 2025 will forever be the first year that Cartter and Scotty braved the frigid waters along with all the revelers who turn out for the annual “Polar Bear Plunge.” We’ve just about got the yearly excursion down to a science: Start the morning with some oats, scarf a couple eggs before heading to Bebop’s house around noon, drink a stiff bloody mary once there, then make another and polish it during the mile walk down the beach to where the throng gathers; after all this, a person is well prepared to fully enjoy the spectacle, the chance encounters, and the fifty-four degree bath in the Atlantic. Of course, Cartter and Scotty don’t have the benefit of alcohol.

So well prepared were Danyelle and I that we actually went for seconds at this year’s plunge. On the edge of the hoard, where the crowd was less dense, I asked Danyelle if we were going to wait for all the ceremoniousness that was happening fifty or so yards up the beach. We decided against it and waded out ahead of the masses, puncturing the tension, and enduring the initial shock alone. Returning to the shore a minute later and finding the rest of the partiers poised to make the dash, Scotty and Cartter among them, we plunged a second time.

I was hardly out of the water when the stampede began. Searching for the boys, I turned around and saw Scotty sprinting out toward the ocean, a lone brave yearling galloping well beneath the shoulders of the surrounding herd, unconcerned with whether his parents joined him. He had a different sort of determination and deftness to his step compared to his brother, who, nearby, moved without so much reckless abandon. Pausing in waist deep water, Scotty bounced and hyperventilated like any sane person would, but his face remained calm, bearing the look of resolve one might notice on a quarterback who, despite the deficit showing on the scoreboard, knows he’s going to lead his team to victory. I waded past him and beckoned him deeper, reaching my arms toward him and inching away like when his mother and I taught him to swim, but he did not heed me. The boy had a mission to complete, and it was his alone. He checked his mother standing off to his right, said, “I’m going under,” and with a quick nod to confirm her approval, dove.

As he did so, he turned away from me and toward the beach, lifting his face so that when he hit the water, his body immediately rose to the surface where it lay momentarily suspended and motionless. Everything got wet except the crown of his head. A strong swimmer for his age, the child still hasn’t mastered how to steer with his hands, to tuck his chin, to use his upper torso and control his body through his midsection. In that frozen moment while he floated there in his blue trunks and teal swim shirt, he reminded me of when I embarrassed myself during one of my first summers on the Wild Dunes Dolphins swim team. The coach had assembled us on the deck and instructed us to dive in and streamline under water as far as we could, and after one of the older swimmers demonstrated, he selected me to go next. Not understanding, I dove in and skimmed the surface, floating there for what I thought a passable amount of time. When I lifted my head, barely five yards from the wall, all of my older teammates were laughing at me. No doubt the hilarity had a lot to do with my smallness and my innocence.

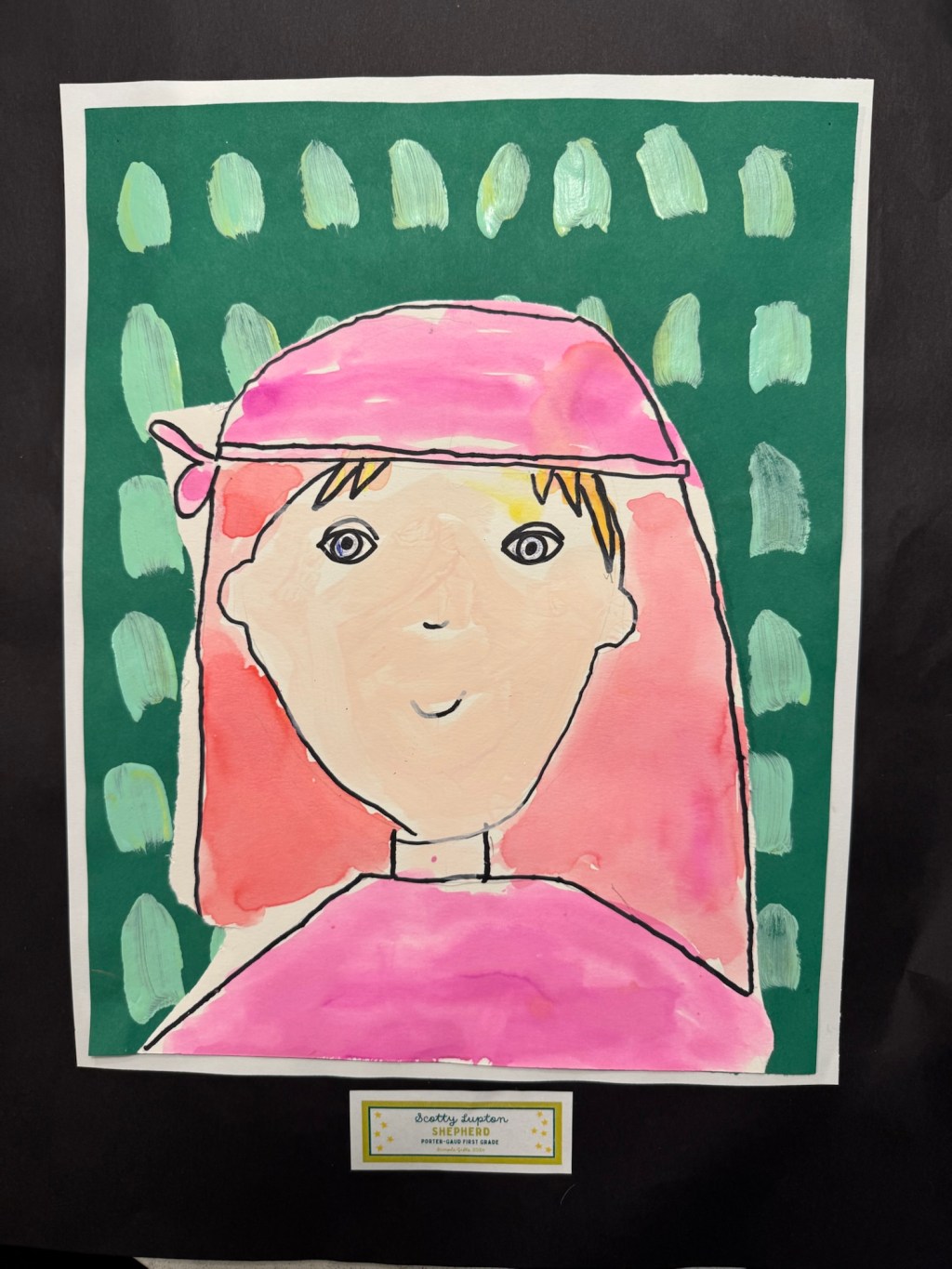

As a parent I enjoy a clearer picture of my child’s soul than my former teammates did of mine; Scotty’s calm resolve, his fearlessness, his assuredness in the way he goes about his life, the sight of these things has often brought a smirk to my lips as I’ve marveled at the small package in which they reside. He was the tiniest bather I saw of the thousands on the beach on New Year’s Day. Likewise, as a baby he was the tiniest crawler I ever saw, rising up on all fours at a shockingly young age. He became so proficient at crawling that he delayed walking in favor of a bear crawl, scurrying around on hands and feet like a feral human animal with its diapered butt aimed up in the air. At five he became the tiniest serious trail hiker I’ve ever encountered, easily passing through thorny brush and scaling peaks I didn’t reach until I was a teen. Sitting next to me in the living room the evening after his first “polar plunge,” asking me about Jack London, he was the picture of a tiny bibliophile.

“Why do we have emotions?” he asked after my remark about the hardship and sadness that permeates Jack London’s classic novel.

I thought a moment and offered that perhaps it’s because, “They help us.”

“What about anger and sadness, though?” he asked. “They don’t help us with anything.”

“Well,” I said, “we can think about why we’re angry or sad, and that can help.”

“What would we be like if we didn’t have emotions?”

“Robots.”

“Would we talk funny?”

“Maybe.”

By the time our conversation reached this point, it was too close to bedtime to tackle The Call of the Wild. Scotty moved to a table across the room, where there stood a little box set filled with slim volumes from a series called, I Survived. These, he pulled with his index finger one by one. When I explained that he could read the titles on the spines, he countered that he “wanted to see the covers,” and ultimately selected one bearing the image of a fearsome shark breaking the surface with jaws opened wide, much to the terror of two nearby boys running from the water. Thus equipped, he retired to his bedroom, a tiny reader secure in his choice of material, and I, his father, smirked at the ease and grace with which he took his leave.