A couple with children the same age as ours, one whose company Danyelle and I both truly enjoy, one we invite over for dinner and drinks; adult friends who fit into our lives in a way that is neither forced nor left over from the time before we had kids – long have I waited to find these people, yet as I sit in the Kinningers’ kitchen, sated by hours of conversation and easy laughter, I catch Danyelle’s eye across the island countertop littered with empty cans and pizza boxes and quietly confess, “I’m a little sad.”

The sun is setting on a cool October Friday evening, and the dim glow of the chandelier surrounds us as darkness makes its slow, steady descent. It’s about the time when Danyelle and I would normally be hauling the kids home in the minivan after a family night out for dinner, but this afternoon, we took the golfcart to our friends’ house, and although Danyelle and I are about to leave, Cartter and Scotty aren’t coming with us. They’re spending the night.

All throughout this little get together, questions about a sleepover have periodically interrupted adult conversations. After each noncommittal answer – “We’ll see,” “Let us talk about it,” “That doesn’t mean yes,” – a little boy scurried off excitedly to his two co-conspirators to give an update on their progress: “I think your mom said yes!” With a long weekend ahead, and the boys so eager and hopeful, all four parents seemed to view their eventual capitulation as inevitable. The boys beheld our pending permission as hungry savages might a suckling pig turning over a crackling fire, and nobody wanted to deny them. I remember when Cartter and Scotty were toddlers discussing with another dad the sometimes-frustrating chore of feeding them. “It’s so satisfying when they eat, isn’t it?” my friend said. It was. It still is. And seeing them blossom socially brings a similar satisfaction.

Lately, the boys’ social appetite has increased exponentially. Outings with their mother and me, whether to the beach or their grandfather’s house or the county park – excursions that used to bring them great joy – nowadays often serve only to highlight the absence of their friends. “We could stay and hang out a while longer,” I said to Cartter on a recent Sunday morning at the park. We’d picnicked by the water and strolled to the playground where the boys spent about fifteen minutes climbing the equipment. A year ago, Danyelle and I could have passed another hour seated on a bench talking and watching them play. On this occasion, though, the possibility of a Sunday afternoon gang getting together in the neighborhood loomed far too large in Cartter’s mind. “But our friends,” he said.

Our day at the park had been about as palatable as a bag of Doritos that’s been open a little too long, its pleasing flavor and lingering bite just enough to delay one’s conclusion that the chips have gone stale. We arrived not knowing that a music festival headlined by an Allman Brothers tribute band was taking place that afternoon. Families set up blankets and chairs in the lawn, and as the four of us struck out on the trail that loops through the marsh, we found the boardwalks and pathways through the island jungles completely abandoned. Two years ago, we spent a crisp winter morning in the playground beneath the observation tower that looks out toward the Wando River. Afterwards, we took the kids to the movies. They were thrilled. I’m more than a little fond of that memory, but walking around the deserted trail while the boys’ thoughts drifted to their friends felt like passing through the shadow of its ghost. The air hung still and thick; mosquitoes swarmed; the sun shone with stubborn warmth; and new measuring sticks planted in the earth displayed the ever-rising tides’ highwater marks while a steady drumbeat pounded through the not-too-distant sound system. Even though I tend toward nostalgia, after finishing our walk and watching the boys climb dutifully and straight-faced over the playground equipment, I had to agree with Cartter. It was time to move on.

The neighborhood playground nestled in a corner of the wooded communal grounds, the historic Charles Towne Landing – site of the original colonial settlement in what is now South Carolina, the old rice plantations along the Ashley River: just a few of the places Danyelle and I enjoyed family outings with the boys. We packed lunches and pushed them in swings and strollers. They rode scooters to keep up while the two of us walked. To be out in the world, with their parents nearby, it was fulfillment enough for Cartter and Scotty, which was enough for Danyelle and me. We ambled through beautiful gardens and sprawling antebellum marshfront properties, often exhausted, making the most of the ever-present need to entertain the kids. We had a purpose, a reason to be all these places we frequented. Our own enjoyment was secondary to passing the time without the kids fighting. It was a labor of love, and it was uncomplicated. That, I will miss, but we also suffered petting zoos and public restroom debacles, the noisy playground under the Ravenel Bridge, the children’s museum. I’m happy to leave those behind, and more importantly, so are the kids. To them, visiting old haunts with their parents is a thin gruel compared to the bountiful feast that is time spent with friends.

Knowledge of the boys’ happiness trumps my fleeting nostalgia as I stand in the doorway to our friends’ garage about to make my second and final departure before the sleepover begins in earnest. “Do you think either of them will get scared and need to go home?” Sam, the mother of the house, asks me. At first, I don’t notice the seriousness in her wide eyes and brush the question off, taking a step out the door lest I run out my welcome. “It’s happened before,” she continues. “One parent gave us a heads up, and it helped. We were ready when we had to bring her son home in the middle of the night.” Her tone betrays nary a hint of annoyance or disgust. Rather, it’s compassionate, encouraging. A nurse anesthetist at the local children’s hospital, the mother of three very sharp, very personable young children, reserved, intelligent, and with an air of responsibility about her, Sam is a person I intuitively look up to. Faced with her gentle concern, one foot out the door, I don’t want to disappoint her. I pause, weighing in my mind the odds of the kids suffering some sort of breakdown during their first sleepover away from home.

A half hour before, when Danyelle and I left after dinner, we’d been giddy, high off the good time we’d had with our friends, in slight disbelief that the kids weren’t coming home with us. The golfcart ride back to the house had been chilly, and we laughed and shivered as we zoomed down quiet neighborhood roads. By the time I made it back to our friends’ house with provisions for the boys, darkness had fully set in. I administered Scotty’s inhaler, ushered him and his brother into the hallway bathroom to brush their teeth, and presented them a couple of favored stuffed animals, all while weaving in and out of Sam’s path, trying to lessen her burden without appearing untrusting. I know how sensitive our boys can be, particularly Cartter. He has enough trouble falling asleep in his own bed every night. He’s afraid of the dark. He tends to be indirect when asking for things. With this knowledge in mind, I gave the boys a little speech before leaving their friend’s bedroom, instructing them to ask Mr. and Mrs. Kinninger if they needed anything, ensuring them that Mommy and Daddy were just a phone call away and not to worry. It was a little clumsy, and I can see how it could have made another parent anxious; however, as I stood on the threshold of leaving my boys in her care, Sam seemed less anxious than sympathetic. “We had to go get Lily (her older daughter) from James Island at midnight once,” she said with a slight laugh. For a moment I relaxed. Smiling back at her and her husband standing in the kitchen as I paused my escape, my gratitude was twofold. One, I was sure the boys couldn’t have picked a better home for their first sleepover, and two, I realized it would take a catastrophe of epic proportions for them to wuss out. No way they were going to blow this opportunity.

The sleepover is undoubtedly the Holy Grail of kid bonding. To sleep over is to defeat that awful creeping fear of missing out, to stretch the absence of boredom over multiple days, to fully indulge the need for companionship. It’s the kid equivalent of “making it official.” If you sleep over, you’re best friends. My first sleep over of real consequence that I remember was with a third-grade classmate named Lyles. It was my introduction to Man Hunt (a combination of hide-and-seek and tag), Mortal Kombat (on Super Nintendo), and cursing. As a fourth grader, I slept over at a boy named Neal’s house, where I discovered Hot Pockets, Toaster Strudels, and Monte Python. Fifth and sixth grade were down years, during which I wandered through a desert of awkward loneliness. Then, in seventh I met Matt, who still has a shot to be a lifelong friend. I’ve met very few in that class since.

Bennett is the boys’ unrivaled best bud. Years ago they met in the neighborhood playground, and since then they’ve gradually become closer. Once Bennett spent the night at our house over the summer, the deal was sealed. The three boys were fully committed. Bennett is a second grader, positioned perfectly between Cartter and Scotty, who are in third and first respectively, and he seems to see in us a kind of mirror image of his own family. The middle child between two sisters, with his blond hair and his slightly serious, pensive look, he somewhat resembles Cartter. When out in public, he’s often mistaken for a third brother, a mix-up that brings a happy little closed-lip smile to his face. His mother explained it to Danyelle and me thusly: “I think he wants you guys to adopt him.” Cartter and Scotty wouldn’t complain. Whoever said three’s a crowd clearly didn’t know the likes of these three. Bennett is Cartter’s best friend, and he is Scotty’s best friend, and Cartter and Scotty are Bennett’s best friend.

Danyelle and I find the arrangement agreeable. In my work as a coach, I’ve met a lot of young kids, and as eight-year-old boys go, Bennett is pretty tolerable. He’ll test you, but he isn’t loud or especially disobedient. He has a mischievous streak that’s plain to see when a wicked smile flashes across his face, but he is on the whole what you might call “a good dude.” He has a very energetic older sister, Lily, who both loves him and keeps him in line (there is a story about a so called “Easter Beat Down” that I wish had been captured on video), which in my estimation has been important to the formation of his character. Opinionated about what’s right, and decisive about responding to injustice, he adds a fiercely loyal, scrappy element to the boys’ crew. He’s a built-in arbiter in the event of a brotherly squabble and a vocal deterrent to any potential outside abuser. When the kid across the street tries to pick on Scotty in Bennett’s presence, he finds himself promptly knocked on his ass. Danyelle and I are more than okay with Bennett. What’s more, we love his family, and the boys’ friendship has brought us closer to Bennett’s parents. As we find ourselves finally emerging from the insularity of parenthood’s early years, an insularity exacerbated by a pandemic in our case, we’re happy to meet people we like and make friends. However sad I might be that the perfect closeness and clarity of purpose of early childhood are starting to fade in the rearview, I’m at least equally excited at the prospect of what’s taking their place: freedom and burgeoning friendships, both for the kids and Danyelle and me.

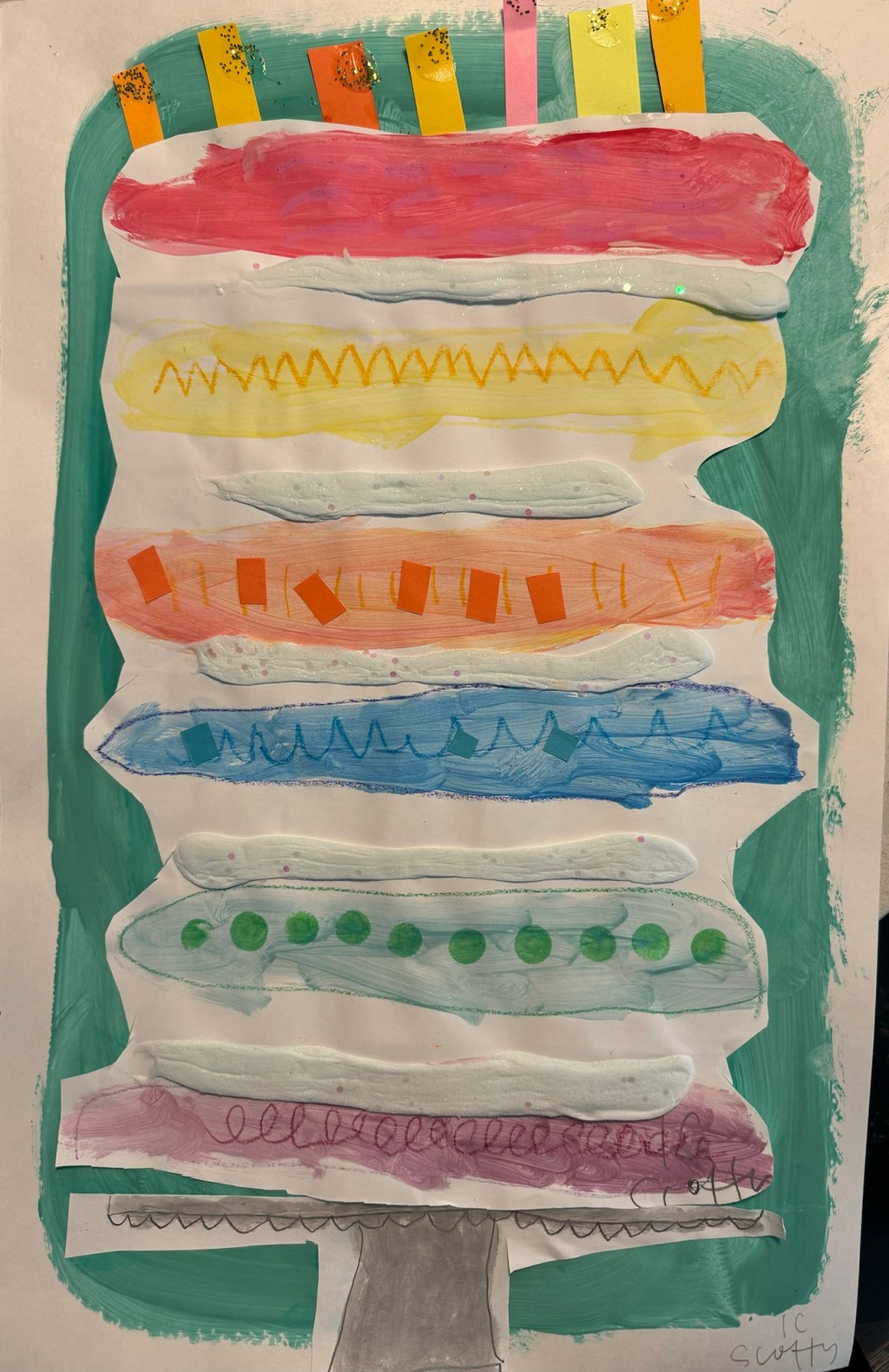

Freedom from the kids is so unusual to me now that after dropping off their things at the Kinningers’, it sneaks up on me so that I don’t even recognize it at first. Danyelle is sitting at the dining room table, working on paper machete mosquitoes to be used as Halloween decorations (this would be how we spent our evening without the kids . . . doing arts and crafts for the kids), and the thought crosses my mind that we’re getting a trial run at being empty nesters, giving me the tiniest rush of exhilaration. Apart from the knowledge that Cartter and Scotty aren’t home, though, I can’t quite put my finger on what’s different. Danyelle points it out in the end. “It’s so nice to sit here with the lights on,” she says. Then I realize that the dining room is normally off limits at this hour, because the lights would shine into the boys’ rooms and keep them up. “And their fans aren’t running,” Danyelle says. Yes, that would explain the silence. Normally, the boys sleep to the drone of box fans so that even after we put them to bed, still, there is noise. Then, it occurrs to me, “Have we ever spent the night in this house without them? Has that ever happened?” After a moment’s thought, we conclude that no, in the eight-and-a-half years since Cartter was born, we have not spent a single night alone together in our home. The time since then has essentially been one massively long sleepover, which I guess makes it official. Cartter and Scotty are our best friends.

Danyelle and I do have lives, however small, outside our kids, and we can function, however awkwardly, in social scenes that have little or nothing to do with them. Generally speaking, though, the time we spend with friends is sporadic at best, and having too many friends is not something of which either of us could seriously be accused. I’ll spare my wife the psychoanalysis, but personally, I’ve been distrustful ever since childhood of how people might view me. I can think of many potential reasons for this tendency: A naturally shy, introverted disposition; the move away from all my extended family just at the outset of my grade school years; a heavily regimented and high-pressure upbringing; the brutal, scarring end to my parents’ marriage during my high school years; the family wealth that has allowed me to avoid ever holding down a “real job” whose title satisfies the question, “What do you do?” Excuses? Maybe, but whatever the explanation for my reluctance to open up to people, the result is that I’ve remained stubbornly detached from social life all the way through childhood, early adulthood and into middle age, relying instead on just a few close friends and immediate family for fulfilling interaction while relegating all others in my orbit to the status of mere acquaintances.

I don’t regret my not-so-robust strategy of social networking. It’s been largely unintentional, maybe even unavoidable to an extent, and it’s hard to fault my somewhat oblivious younger self for that. Moreover, I wouldn’t trade any of the close friends that I have made to this point in my life, nor the loneliness I’ve felt in their absence. To forego either would be to diminish both. Still, pleased as I may be with my experience thus far, the leaner times were often painful to endure, and I’d like to avoid them going forward. Moreover, I’d like my boys to avoid them as well and to enjoy instead a more regular diet if you will. Together with Danyelle, I’ve tried to position Cartter and Scotty for a more natural social life than I’ve led, first and foremost by choosing to live in a suburban subdivision that enables their freedom and exposes them to lots of other kids.

Growing up on the front beach on Sullivan’s Island, falling asleep and waking up to the sound of the waves breaking against the shore, was no doubt a privilege, and it was one I never took for granted. From the moment we arrived just weeks before my sixth birthday, the house on Marshall Blvd. seemed like a dream. The view of the ocean, the smell of the salt air, each sunrise at the start of a new day was almost too good to be true. There were not, however, a lot of island kids my own age. I played basketball with David who lived on the other side of the empty lot next to us, but he was two years younger than I was. Then there was Peter, who lived a few blocks away and rode his bike to school with me every day in second grade, but beyond those two, it was slim pickings. By contrast, the morning after the boys’ big sleepover, after Danyelle has picked them up and whisked them and Bennett to an event billed as “Lego Masters,” I answer a ring of our doorbell and am greeted by three boys who want to know if Cartter and Scotty are available to play kickball. This is nothing out of the ordinary. Just the other day, Danyelle ended up feeding five little boys dinner on a school night. A few days before that, there were at one point ten boys in our den, all of whom with the exception of Bennett, live on our little section of Scotland Drive, and nine of whom are between six and eight years old. They assembled Legos on the floor and talked until Cartter appeared in the kitchen and announced to Danyelle and me, “We’re going over to Tommy’s,” to which we both simultaneously replied, “Oh, you are?” Once they’d all cleared out, Danyelle and I looked at each other and burst out laughing. “They’re bar hopping,” I said.

The boy gang of lower Scotland, of which Bennett is an honorary member, enjoys quite an enviable lifestyle. When the crew gathers, it passes the time building forts, “making Legos,” digging holes, playing kickball and soccer, riding bikes, and generally roaming the neighborhood. These gatherings are the reason that Cartter would prefer to stay home on Sunday instead of going out with Danyelle and me, and they’re the reason that Danyelle and I are tentative about overscheduling afterschool activities. A piano lesson or another swim practice has to be weighed against the loss of free play that is so obviously valuable to Cartter and Scotty. I ran up against possies like these as a kid. The game of Man Hunt that I played with Lyles during that third-grade sleepover was a neighborhood-wide event, and through staying over at Matt’s house, I was introduced to a little gang of downtown kids. I watched them play Golden Eye on Super Nintendo, rode around in the car and smoked weed with them, and grew closer to some of them over the years, but on the whole, I tended to feel a bit of a tourist in their midst. Really, I preferred to spend time with just Matt and to exist in the group as a kind of guest, neither unwelcome nor obligated. Again, I don’t regret my earlier approach to social existence, but I would be happy, indeed I am happy, for my kids to function more easily in a larger group.

The boys report that they prefer their neighborhood friends to their school friends, expressing frustration at the fact that at school, all their activities are directed by adults. I like to think that their free roaming social existence at this early stage in life will translate into a well-adjusted adulthood. It seems obvious that social freedom as a child and coping skills as an adult would be correlated. My close friend Stratton is probably the most sociable person I’ve ever known, and he claims to have had a similar neighborhood experience as a child. Certainly, things seems to have worked out how I imagine in his case. When Stratton and I first started hanging out a lot in my early twenties, he stood in the kitchen of my one-bedroom apartment and told me, “Some people take a long time to make friends, but I make friends like that,” and he snapped his fingers to indicate the instantaneousness of his friend-making. The boys are showing signs of a similar ease. “I made friends with Teddy today,” Scotty announced in the car after school one day. When asked how that went, he explained, “I looked at him, and I said, ‘Do you wanna be friends?’ and he said, ‘yeah.’” I’m doing my best to co-opt this openhandedness about friendship.

Walking home from dinner on a Saturday night, knocking on a neighbor’s door wouldn’t have been a real consideration at any prior point in my life. Now, no sooner do we round the corner of the Kinningers’ street than they’re ushering us inside and offering us drinks by the pool. It’s a week after the big sleepover, an occasion that ended up going so smoothly, the boys have already duplicated it, this time at our house. They spent the better part of the last 24 hours riding bikes and ferreting around in the park wearing matching camo outfits. They even donned “night vision goggles” and carried a lantern for an evening foray out into the HOA grounds behind the house. That was last night. Tonight, after peeling the trio apart, we marched Cartter and Scotty two miles to the local pub for dinner. The Kinningers’ is about halfway, and on our way back we meant to collect the stuffed animals Scotty left behind a week prior, but everyone seems so happy to see us when we show up on the front stoop that we offer barely any resistance at all when the boys strip down to their underwear and leap into the pool in the back yard. Sam appears with a glass of wine. Her husband Chris is pulling me aside into the living room where his Deion Sanders-led Colorado team is on TV. It’s all reminiscent of that day when Stratton stood in my kitchen and snapped his fingers, scaled up to the level of entire families.

“You wonder how long it will last,” Chris says wistfully once the evening’s through. We’re standing in the front yard at this point, watching the boys roll around nearby gasping for air between bursts of delirious laughter. It’s dark outside, and he’s loaning us his golfcart for the last mile of our journey home. Of course, he’s right: I’ve had just that thought. Childhood friendships tend to peter out. This particular friendship the boys have struck works out quite nicely for Danyelle and me, but as much as I might like to prolong it, if I were a betting man, I wouldn’t venture that this little trio survives middle school or even the remainder of elementary school. The three main pillars of its foundation appear to be a mutual affinity for Legos, camo wear, and fort-building, not exactly the type of stuff that binds people together forever. In the end, Cartter and Scotty’s closeness with Bennett will likely go the way of our family outings to the playground where they once met, relegated to the realm of memory and shrouded in nostalgia. Watching my two sons enjoy what amounts to the first great feast of their young social lives, it’s tempting to wonder what will follow it, maybe even to fear its absence. As someone who has always doubted my own friendships’ staying power, afraid that I would mess everything up, be discovered as uncool, and end up dumped, part of me wants to have a contingency plan in place for them. Somehow, I’m reminded of my grandmother rebuking me for my angst about getting the boys on a regular feeding schedule when they were both still in diapers. “Don’t you know about babies?” she scoffed. “They eat when they’re hungry.” In other words, the parent has to let them lead. Loosening the reins and seeing the boys flourish socially has been more rewarding than I could have hoped. I’m sad that in terms of company I’m not their first choice anymore, but I’m proud at seeing them thrive. What’s more, I’m happy to benefit from it.