I’ve had about enough by the time my third-grade son’s reading teacher pushes the little stack of papers toward me again. “If you’ll just help him with these questions . . .” she says for the third time. She wants Cartter to speak up more in class, to present himself more confidently. To her, his father drilling him with questions during his time away from school seems a reasonable means to that end. I’ve been looking forward to this encounter for weeks, eager to meet the woman who strikes such fear in my eight-year-old son’s heart that he can’t sleep at night, but now, nearing the end of our little sit-down, I’m not sure whether to cast aside diplomacy and unleash the whole truth.

To my slight annoyance, Miss Teacher began our meeting by keeping me waiting out in the hall for fifteen minutes, thereby ensuring my lateness for the two conferences I have following the one with her. Once we were both seated across a child’s desk from each other, she asked me in a Scottish brogue (yes, the reading teacher is Scottish), “Is there anythin’ ye’d like to tell me before we begin?” She leaned away stiffly and turned her head to one side while I explained simply that I know Cartter is afraid of the pressure he feels at school and chalked his fear up to the fact that he is a naturally shy boy. The details of being called into his room night after night and listening to him tell me in the dark, “Daddy, I’m scared,” the little hand clutching my arm and the quiet confession muffled into a pillow that the source of his fear is, “Reading class,” all that unpleasantness I left out in the name of cordiality, but it was implied.

I thought my handling of Miss Teacher’s tardy and somewhat brusque introduction was about as smooth as I could’ve made it, and with that business out of the way, it was now my turn to sit and listen. Miss Teacher reported that Cartter’s current reading level is off the third-grade chart and that when he is asked to give answers in writing, they’re more than satisfactory. Considering Cartter’s obvious academic aptitude, his consistent completion of all assigned work, and the absence of behavioral issues, it seemed to me that Miss Teacher should have no complaints. She felt differently, however, and prattled on, seemingly disappointed and befuddled at Cartter’s reluctance to open up to her, periodically pushing the list of questions toward me.

As she did so, I noticed her thin blond curls, her round red face, her fat ankles stuffed into little pink boots. I’m no fashion connoisseur, but for women who bear a natural likeness to Miss Piggy, footwear that resembles hooves strikes me as a poor choice. Such a choice would seem to indicate a lack of self-awareness, as would continuing to push one’s pedagogical expertise in response to apparent failure, opting instead to foist responsibility onto a parent while insisting that an exceedingly bright yet timid eight-year-old improve his performance in oral assessments. More than her lack of fashion sense or her displeasing appearance, it’s this lack of self-awareness that I find particularly unattractive, which brings me back to my dilemma.

As I glance down at the small, single-spaced print on the pages being thrust at me and hear again the demand that I tackle this assignment with my son, I can’t be sure whether I’m motivated by a desire to help my child or the urge to hold a mirror up to this teacher’s flaws. A lusty appetite for confrontation rises from the pit of my stomach into my chest when I’m prompted for the third time to drill Cartter at home, and it clouds my mental calculus. I can’t decide whether the right thing to do would be to look this unwitting Miss Piggy in the eye and tell her in no uncertain terms that, “I won’t be doing that. I’m not gonna treat my kid like a test subject.”

If the point is to irritate me and knock me off balance, this teacher has succeeded, but she has not succeeded in convincing me that Cartter needs any extra academic pressure. As I concentrate on keeping a poker face and managing my response, I can’t for the life of me imagine why she isn’t satisfied with my son. Not until later in the day will I realize that her preoccupation with Cartter’s reticence in her class has nothing to do with his learning, and everything to do with the image she has of herself as a kind of child whisperer. It will dawn on me that she sees herself as a breeder of academic champions, of confident pupils who go on to be (as she puts it) “very successful.”

She’s like the swim coaches I know who place inordinate importance on the performance of very young athletes. They chase ten-and-unders up and down the pool deck yelling and gesticulating wildly during races at meets, shouting praise when their swimmer touches the wall first or goes a best time. Teaching fundamentals that serve an athlete’s long-term development isn’t enough to satisfy these coaches. They want credit for the results, and they want it now. Blatant favoritism, undue pressure on immature swimmers, the prevailing evidence that early performance doesn’t indicate future success – none of that matters to the jump-around coach. They want validation.

I can’t quite think through it while I’m sitting across from her, but when Miss Teacher looks at Cartter, she sees big time validation potential, and the problem is that he’s not giving her what she wants. He’ll gladly sit around devouring texts, and he’ll do whatever assignment is required, but he isn’t one of those kids who’s going to lay it all on the line just to please a coach or a teacher. The youngest kid in his grade, he’s cautious about extending himself, and he shies away from other people’s excitement, preferring his independence to their expectations.

“You know,” he once told me while I was coaching him up on the driveway hoop, “I’m never gonna be the best at basketball.” A profound observation by a then seven-year-old, I thought, one that stopped me in my tracks and forced me to question what I was doing with him. Was it about him? Or me? Watching Cartter steer clear of the bigger, more aggressive boys in his basketball practices, I’m reminded of the swim parents who have approached me over the years and complained about a child who’s coming to practice regularly, doing what they’re supposed to do, and failing to race to their potential in the meets. “If little Suzi could just find that competitive spark!” they say. I always think something to the effect of, “The kid’s eight. What difference does it make? Just don’t worry about it.” It’s what I’d like to tell Miss Teacher when she keeps pressing me, pushing all that standardized fine print at me, but, of course, I put a cork in it.

Rageful impulses successfully repressed, I stand to leave the room, papers in hand, and try to be friendly. This is my kid’s teacher I’m dealing with after all. No sense pissing her off. Better to make a connection. I figure that since she’s a Scot and a reading teacher, some of the British literature I’ve recently encountered might be up her alley. “I just finished reading Watership Down with the kids,” I say. “You know that one?” She’s seen the film. “What about James Herriott? He wasn’t Scottish, but all his stuff is about a town called Danbury, near the border.” She’s never heard of him. “What about The Secret Garden?” I ask. “That author is Scottish. The whole thing takes place in the moors, and it’s full of Scottish dialogue. I read it to Cartter a couple years ago, and he loved it.” Again, she’s never heard of it. I decide to abandon the whole British angle and go to something everyone surely knows. “Tom Sawyer is next on our reading list with the kids,” I offer. To my dismay, I learn that this woman who likes to pass herself off as an expert teacher of children’s literature has never read The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. I’m reminded of when I was brought near to tears by a teacher friend who told me she was forbidden to teach novels in her language arts class at a public middle school in Hartsville, SC.

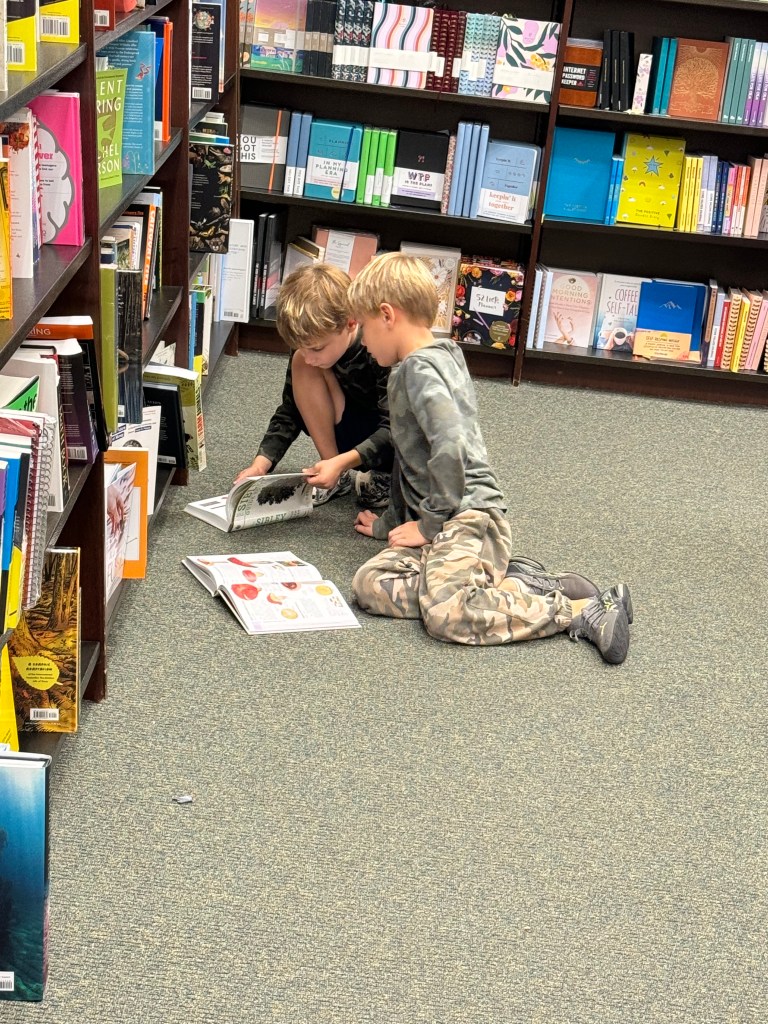

I think I may have accidentally humiliated Miss Teacher, and as I’m about to walk out the door and into the hallway where she once kept me waiting, she makes a final attempt at saving face: “Ah always say that s’long as they leave muh class with a loave of readin’, ah’ve done muh job.” I picture Cartter the night before, Halloween night. After he and his brother and their three friends came back to the house and sat at the dining room table for a half hour divvying up and sampling their loot, he wandered over to the kitchen. The Halloween celebration continued around him, but he sat by himself for a while, curled up on a stool beneath the overhead lights, absorbed in a book.

“Well, Cartter already loves to read,” I say. What I don’t say as we exchange purse-lipped smiles and make our final farewells is, “All you have to do is not fuck it up.”