Driving away from my children’s school on a Friday afternoon in early October, I’m distracted enough to make it the full length of the city’s seawall without fully understanding the discussion going on between my six-year-old in the backseat and my wife sitting next to me. The light rain falling on the minivan’s windshield is dissipating, and to the west of the Ashley River the kids’ school has faded from sight. We’re heading toward lighter skies and away from a darker, indecisive shade of gray. As I round the southernmost tip of the peninsula, the rain stops, and my mood is buoyed by the fullness of the weekend that lies ahead. I’m almost lulled into a state of indifference by the nonchalance with which Scotty’s voice rises from the backseat. “I asked my teacher if I could go to the lost and found today,” he says, “and she said she would take me, but then she forgot.” Of course. He’s left his lunchbox at school again, and, of course, his teacher is no help. Disappointing, but still, family Friday awaits. A lazy afternoon at a picnic table next to a favorite grand oak, the kids content on the quiet playground beneath its canopy, a beer and a pie at a hole in the wall pizzeria: so many reasons not to be angry about my young son’s characteristic absentmindedness. It’s not until I pull into a parallel parking spot near the hidden entrance to our favorite after school playground that I finally grasp the absurdity of what’s transpired. The car still running, I look to my wife in the passenger seat and squint as if trying to see through a fog: “Are you telling me he lost two lunchboxes in two days?”

This habit of misplacing things is one both my boys share, but Scotty is particularly gifted in the art of losing stuff. He loses books, shoes, water bottles, sports equipment – rest assured, anything placed in his possession will be lost and lost quickly. I do not consider myself a materialistic person, but this ability to totally disregard the value of one’s things is foreign to me. As a child, shoes allowed me to run on courts, fields, and gym floors; goggles let me see underwater; and schoolbooks were my ticket into adults’ good graces. Respecting one’s belongings was a lesson sometimes preached by my parents, but it wasn’t one I needed to hear all that often. The few things I owned were treasures and not to be handled loosely if I wanted to continue to enjoy their benefit. After all, there was no Amazon Prime in the 1990’s, no “buy now with one click” buttons or free two-day shipping. Losing things hurt more back then. Now, things are replaced almost as thoughtlessly as they’re lost.

Not that online retail is any excuse. I don’t mean to socialize the responsibility for my kids’ behavior. Danyelle and I are the ones who decide to continue buying more and more water bottles and lunchboxes, thereby demonstrating their cheap abundance even as we insist on their preciousness to the kids. Surely, we have only ourselves to blame, but what’s a loving parent to do? As much as we want our kids to learn to respect their personal property, we still want them to have shoes on their feet, and no amount of fire and brimstone sermonizing seems to undo their carelessness. These are the facts, and as my wife confirms the extent of Scotty’s recent negligence, I’m resigned to them. Turning my gaze away from Danyelle and toward the leaves rustling above the park entrance, there’s a calm gravity to my voice. “Well,” I say. “Yelling at him didn’t work. Looks like we’re going to have to come up with a real punishment.”

I might not be able to relate to Scotty’s uncanny ability to lose any and everything entrusted to him, but the terror emanating from the seat behind me – unknown punishment looming, parental love seemingly suspended – is something with which I’m familiar. When I was a few years older than Scotty is now, my parents required that I practice all my songs on the piano before I went out to play. One day, they discovered I’d been skipping a tune, a delicate little Mozart sonatina whose lilting beauty was impossible to rush. For months, unable to speed through its surprising little twists and turns, I’d declined to play it at all. When my parents found me out and asked me to perform the piece for them while they sat in the living room, I hoped against hope that my fingers would somehow find the right notes. Instead, they stumbled awkwardly through the first half and came to a halt in the middle, defeated. “You’ve lost our trust,” my father said, “And it’s gonna take some time to earn it back.” Oh, how the tears did flow.

Had my parents screamed at me, I would have known better how to weather the storm. One simply battens down the hatches and waits on the squall to pass, but this measured disdain appeared so effortless as to be sustainable ad infinitum. Its unknowable duration was more than I could bear. Likewise, Scotty quietly endured a tirade about lost lunchboxes three weeks ago but is reduced to whimpering sobs by my calm determination as I steer the van back across the connector, into the rain falling on the Ashley, and toward the boys’ school.

The rant three Fridays prior was one for the ages. “What do you mean you can’t ask your teachers for permission to go get your lunchbox?” I railed driving up the Ravenel Bridge’s steep incline. “What the hell is wrong with your teachers? Do I need to talk to them? Do we need to pull you out of this damn school?” I’d gathered that the boys were afraid of breaking protocol, that in their pea-sized minds the systems of lining up and being marched about campus in a precisely scheduled fashion trumped common sense and decency. One day during the preceding week, Cartter had spotted his brother’s misplaced lunchbox and failed to pick it up. The next day, Scotty misplaced his lunchbox again, and thistime Cartter got it for him . . . but he left behind his own in its place. Among the things I wanted to know were: How is the frequency of this recurrence possible? How can you not realize you’re missing your lunchbox before you leave campus? And, finally, why do you not retrieve it before we drive you away? It was the answer to this last question that had me particularly irked. Somehow, the boys seemed to believe that physically going to recover their misplaced property and thereby correcting their mistake was against the rules. I intended my fiery speech to be a controlled burn through the forest of their thoughts, one that would clear out any brush piles of doubt regarding the primacy of my authority. In hindsight, Scotty must have viewed it more like an unexpectedly large burst of flame, the likes of which one might dodge after dousing a small mound of lit coals with lighter fluid. Eyes wide and questioning, little mouth slightly parted, he assured me from his booster seat that he understood. Then he realized his brow didn’t even get singed.

Still, I think raising my voice had some positive impact. As long as yelling is a choice, it can serve a purpose. After this latest confession, Scotty is no doubt expecting another wave of loud, masculine noise, and its absence heightens his sense of horror at what’s unfolding. His mother landed quickly upon a punishment: no playing with his friends this weekend, which sounds about as awful to me as it must sound to him, but what’s worse – we’re getting closer to his school, and I’m planning to go in. Still worse, I’m taking him in with me. Exiting the connector, the rain has stopped again, and Scotty starts trying to beg his way out of the approaching ordeal only to be continually rebuffed by my stubborn restraint. “But I’m crying!” he protests.

“That’s fine.” My eyes are on the stoplight nearest the entrance to campus.

“But it’s going to be embarrassing!”

“Well, you better suck it up then.” I’m at the stop sign, about to drive down the road that curves around the soccer field and ends at the elementary school office.

“But I can’t!”

“That’s fine too.” I’m parked in a visitor spot outside the office, and Cartter is worried I’m breaking the rules.

“Come on Scotty.”

Approaching the maglock gate that guards the school’s entrance, my sweet little first-grader is reabsorbing his tears, and I can’t help but think of my mother. A generation ago when I attended this same school, there were no locked gates, no security personnel wearing black shirts, no 200-page parent handbooks to be signed. Columbine was still an anomaly, and the distance between parents and school was easy and natural, not something that had to be enforced. Mom took full advantage of this easy access one morning my senior year in high school. Frustrated by my persistent marijuana use and heated after an ugly exchange during the car ride over, she burst through the school’s main door and marched to the room of my favorite English teacher while I waited, embarrassed and angry, in the car. When she returned, I proceeded, on her orders, to my teacher’s room before the first bell.

Alone in his classroom, we each sat down at adjacent desks, and he pulled out his chair to turn and face me. “Your mother asked me to talk to you about your problem,” he said.

“What problem?”

“Your cannabis problem.” The overhead lights gleamed off the bald dome of his head, and the usual authority in his slightly deep, slightly southern drawl was somewhat off key. Not, I gathered, how he’d hoped to start his morning. I honestly hadn’t expected this, for my mother to out me to my teacher and risk me getting into trouble. What was this man supposed to do for me? Undoubtedly, he was an experienced drug user himself, a lover of modernist poetry who wore skinny ties and joked about “clean living.” I’m sure Mom knew. Had she simply wanted to yell at him too? Was her plan to condemn us both to a shameful conversation in which we were both guilty? Whatever her intent, the situation was unacceptable.

“Did she tell you she had an affair with my swim coach and left my dad?” I said. At that, the man put his hands up and leaned away, looking at once overwhelmed and relieved. The conversation was over.

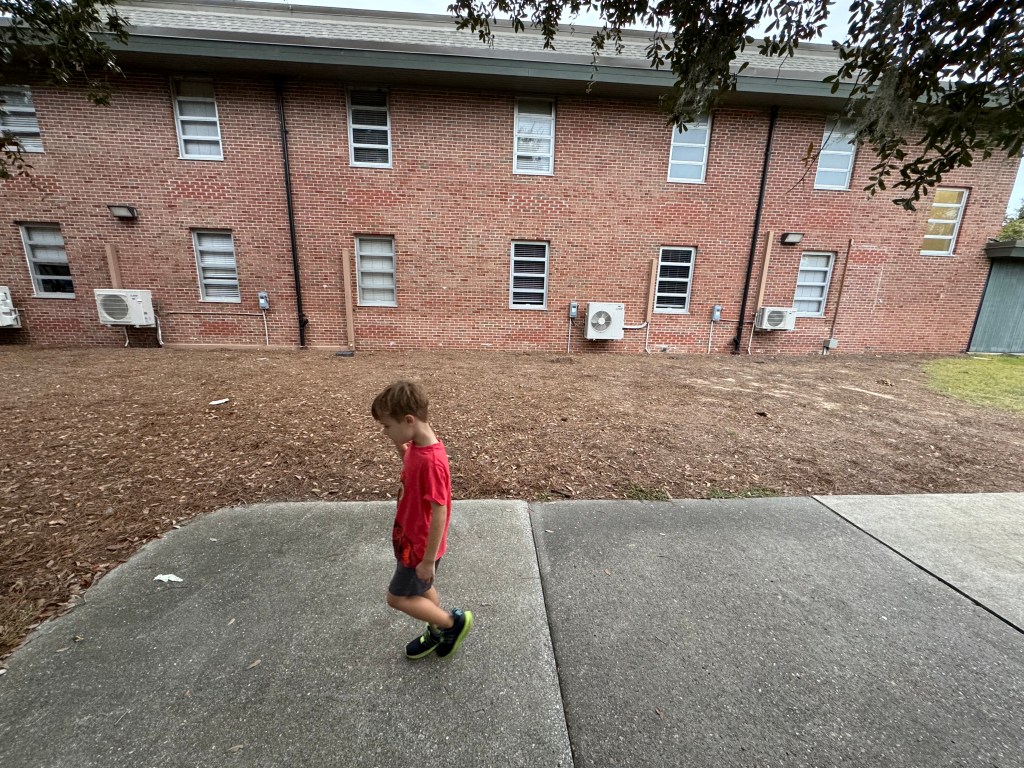

After a friendly extended day counselor sees me and lets us in, and after we retrieve the first of Scotty’s lunchboxes from the front office lost and found, part of me wants to get stopped by some administrator, preferably the elementary school principal. I think I’d like for him to tell me that I can’t be on campus and then to have a Mom-style confrontation with him. “You know,” I might say, “if you guys weren’t so incompetent at feeding the kids lunch, this wouldn’t be a problem,” but as Scotty and I round the cafeteria building and head for the playground, no one approaches me. Kids run in the field; they leap at counselors who fend them off; the few teachers left on campus watch with the faintest of interest; and I stroll up the cement path with Scotty, who is clearly coming round to the notion that this isn’t going to end so badly after all.

“Is this the way you walk after lunch?” I ask him. His eyes are dry now, and he’s talking, filling me in on the little details of his daily marching orders. I peek at him walking next to me and notice he’s craning his neck in an effort to get a look at my face, his blue eyes staring from beneath neat brown eyebrows that are just a touch darker than you’d expect. “He looks just like you,” people say. “But with his mother’s eyes.” A striking little fellow in his disheveled school uniform, everything about him seems to say, “I belong,” and as the two of us make our way conspicuously to the bench where he’s left yet another lunchbox, no one gives us so much as a second look.

“Show me where you line up after recess,” I tell him once he has the second lunchbox in hand, and he leads us to the opposite end of the playground. Now, I see the problem. He comes to the playground from one end, depositing his lunchbox there when he does, and he leaves from the other end, hastened by teachers’ commands to line up. “This is where you’re going to leave your lunchbox at the start of recess from now on,” I tell him pointing to a bench that he passes by every day on his way back to the classroom. “Show me where you go from here.” He does, and we make for the exit.

Our circuitous path back to the car takes us past the first-grade hallway and to a different gate than the one through which we entered. Whether or not the desired effect will be had, I’m satisfied with how things have gone. Not only did we recover the lunchboxes, but what started with tears and frustration has ended up being a sort of pleasant little date. I’m almost sad that it’s about to end. Feeling the need to put a bow on things before rejoining Danyelle and Cartter in the minivan, I stop and turn to Scotty before pushing the gate open. “We aren’t going to punish you or lock you in your room all weekend or anything like that,” I tell him. “But you’ve got to stick to the plan and stop leaving your lunchbox at school.” Scotty agrees and rushes ahead of me to the minivan.

Rounding the tip of the peninsula a second time, I head for the same parking spot we left a half hour before. Scotty and Cartter spend nearly two hours climbing the little jungle gym at the edge of the grand oak’s canopy. They spin each other on the merry-go-rounds, and Scotty laughs so that you can see the gap where his two front teeth are growing in. We dine at a tiny booth in an east side pizzeria. We scoop ice cream on top of Eggo waffles back at the house. We continue reading a marvelous novel about a band of wild rabbits’ struggles for survival. A Mozart sonatina of an afternoon it turns out to be, not to be rushed or skipped over, and, hopefully, to be remembered. Along with Scotty’s lunchbox.