When I was a boy, my Poppin would wake me up at dawn to go fishing on the Upper Lake. With the attic fan droning in the upstairs bedroom of the Laundry, the house so named for its use four generations prior, I’d lift my head from my pillow and see Poppin’s hulking figure silhouetted in the doorway. “John,” he’d say, “Let’s go.”

Out on the water, I did most of the talking as the canoe glided silently across the lake, our paddles making little momentary eddies that swirled through the black surface and its reflection of the world above. Poppin was subtle about trying to quiet me. “Don’t hit the side of the boat, or the fish will hear us,” he’d say. He would work the holes along the bank shrouded in Rhododendron while I worked the middle, my retrieve growing listless the longer I went without a strike, until finally, my Little Cleo’s treble hook would drag the bottom, and I’d pretend that the lakeweed weighing down the end of my rod was a fish. Poppin was not easily fooled. “You have to reel faster,” he’d say.

Sometimes, we’d head back in with a stringer full of Rainbows and Brookies. Just as often, we’d quit from hunger, skunked. Either way, those walks down the little concrete path away from the boathouse and through the woods to the Laundry were some of the happiest moments of my life.

Part of me never leaves “Sapphire,” the property my family named for the nearby town (if you could call it that) in Transylvania County. Reminders of the different, better life I’ve lived there fill the walls and shelves of my home in South Carolina’s lowcountry. The biggest one is a blown-up photo of the Upper Lake that Poppin took from the dam. In it, I’m standing above the water on the little deck that surrounds the boathouse. I must be about nine in my blue windbreaker, holding a punch-and-throw reel that, judging from the way I’m looking at it, is giving me some trouble. My dad is seated next to me, wearing a bucket hat, looking out at the lake between sips from a can of Coors Light. The photo has a certain oddity that adds to its beauty and mystique. Its top and bottom are nearly indistinguishable, so perfect is the lake’s reflection of my father and me, the boathouse, the surrounding forest of Hemlocks, Pines, and Tulip Poplars, and the sky. A few subtle cues are all that betray the water’s trick: a tiny ripple where my lure just entered, the position of the boathouse on the left instead of the righthand bank, and the diminishment of the mountain we call Sassafras that towers in the background. Staring at the photo upside down is something like waking up on your first day home, thinking you’re still in Sapphire. Turn it right side up, and for a brief moment, the smell of the water returns, and melancholy sets in.

“No, it has to be this way,” I told my wife when we hung it.

“How do you know?”

“Because Poppin must have taken it from the dam, see?”

My great great grandfather started construction of the concrete dam in 1931. John Thomas Lupton I was the original investor in Coca-Cola bottling, and with part of the fortune he made from the Coca-Cola Bottling Company and its franchisees, he bought 1,700 acres of paradise in the temperate rainforest of the Western North Carolina Appalachians. A “Dream Lake” that held only trout – that was his vision for the Upper Lake. Cruelly, he never saw it come to fruition. When he was stricken with appendicitis at Sapphire in the summer of 1933, he was, like so many have been since him, reluctant to return home, and after declining to see a local doctor, his appendix burst. JTL I’s dam was finished in 1934. So far, it has outlasted his children and his children’s children, and three further generations have fished and swum in its reservoir, his Dream Lake.

As an older boy and a younger man, I walked along the top of the dam like it was a balance beam. The steady roar of the waterfall crashing below the spillway filled my ears, a thirty-foot drop to a rocky death on my left, the lake’s calm, black surface just inches below me on the right. Two drastically uneven hemispheres separated by 18 inches of concrete. The effect was slightly dizzying. “If you’re gonna fall,” my dad used to say, “just make sure you fall into the lake.” It seemed a risky proposition to me. I thought it a better idea not to fall. A branch grew over a section of the dam about midway out, and every time I ducked it, the possibility that gravity might trump my father’s advice quickened my heartbeat. Once past the limb, I’d climb up the two steep, narrow steps to the dam’s high point and suck in deep breaths as I worked up my courage. Then, I’d dive headfirst into the lake’s dark, icy embrace, hammering dolphin kicks underwater and sprinting freestyle out to the middle before pulling up with a yell, invigorated.

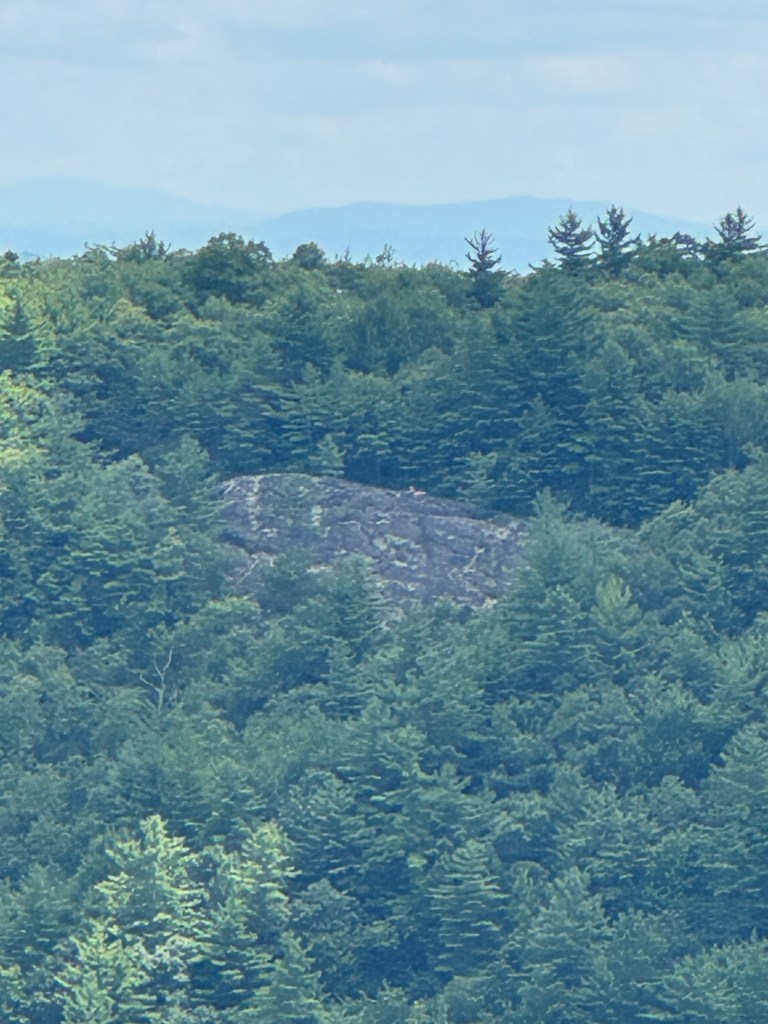

Many times, these plunges followed a brutal hike up Sassafras, atop which there’s an overlook with a panoramic view. From the top of Sassafras, a person can let go savage whoops that echo around the valley and off the side of nearby Nix Mountain. The Upper Lake looks like a little black jewel in the forest floor from there. As a young man at the end of a hike, I’d almost always swim out into the mountain’s reflection, look up towards the spot I’d just been, and silently pray. Then, I’d blow my air out and let myself sink, feeling the water grow colder before quickly losing my nerve and kicking myself back up to the surface.

I haven’t set foot on the dam in some years, nor do I often take out a canoe. I still hike Sassafras, and I still swim in its reflection, but now, some of my earlier reverence for those activities is reserved for the moment I ease away from the dock to take my boys fishing in the little rectangular, flat-bottom boat with a trolling motor. There’s not enough room for the three of us on board, so they have to take turns, one riding with me while the other fishes off the boathouse and waits. Yells echo across the water when the boat gets to the skinny end of the lake away from the dam.

“When’s it gonna be my turn!”

“Just wait!”

“My pole’s stuck!”

“Well, go home then! Or else wait! What do you wanna do!”

And then finally, more quietly, “I’ll wait.”

When I swap one child for another at the boathouse, the boys cast towards each other and tangle their lines before I can motor away. Such is the difficulty of separating them.

“They both look like you, but in a different way,” my friend Matt said when I texted him photos of Cartter and Scotty six years ago. “Like if you took both of them and combined them, it would add up to the total JTL.” Cartter was nearly two, and Scotty was three months old then. Now Cartter is nearly eight, and Scotty is six. Matt’s assessment still holds true, and in more ways than just the boys’ appearance. Their nature is so complementary, their cohesiveness so strong, that being alone on the boat with just one of them, while not as unnerving, gives some of the same surprising sense of lopsidedness as does walking along the top of the dam. Another of the water’s tricks.

Scotty is a philosopher. He watches his lure troll with apparent indifference and casually asks why we haven’t caught any fish. Easygoing and fearless, he’s just as comfortable and perhaps more in his element charging through the thorny brush on a faintly visible trail as he is holding a rod and reel in the front of the boat. As we float atop the glassy water near dusk, a pair of Kingfishers darts and swerves its way across the lake, the two birds weaving in and out of each other’s path before settling on the high branch of a massive pine and issuing rattling calls in our direction.

“I love it here,” I tell my younger son, who simply sits there, expressionless, staring at the water. “When I die, I want them to put some of me here, and some of me along the trail, and some of me up on top of Sassafras.” This sparks his interest.

“You mean you want to get cut up into pieces?” he asks. “I thought when you died, they just put you in the ground, like your whole self, and then they put a tombstone,” he says furrowing his brow, talking with his hands. “How are they gonna put a tombstone in the water?”

He says nothing as I explain cremation, his face returning to its former expressionlessness, his gaze aimed towards the trees now. I can see he understands. Scotty’s world can change on a dime. Ideas and information wash over him and quickly filter through his outer stoicism all the way down to his emotional core. The world is his oyster, and he in turn is its.

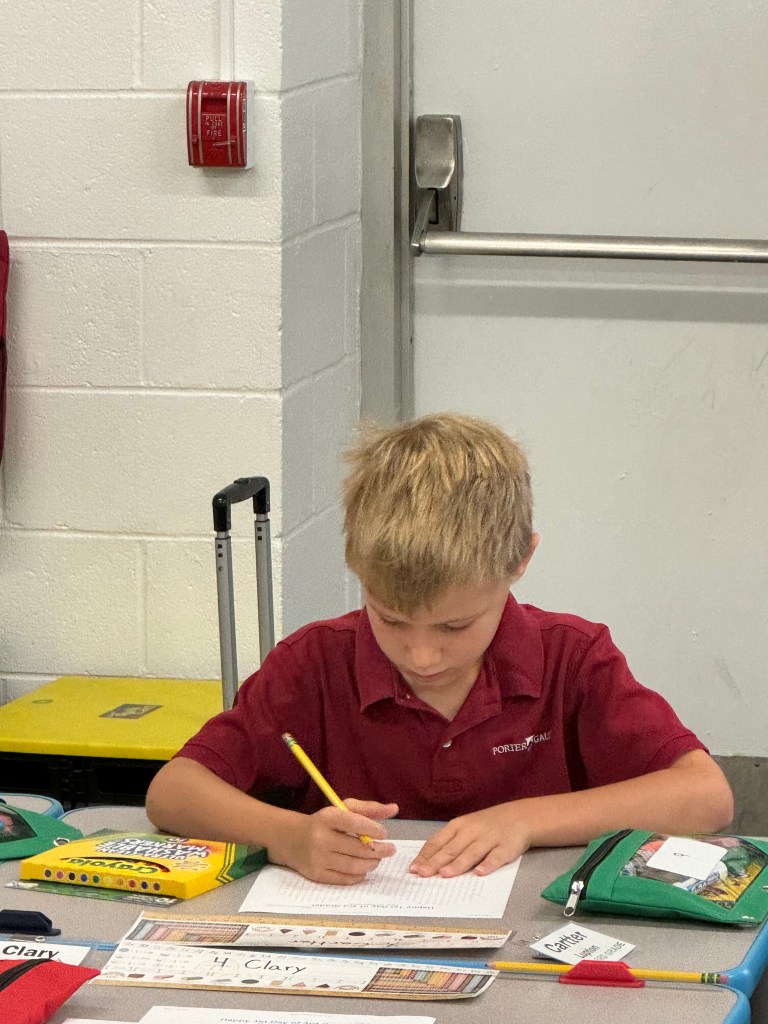

Cartter, on the other hand, is an analyst, who prefers the familiar. Overgrown trails worry him, and he enjoys the repetitive action of casting and reeling, aiming, concentrating. It has a meditative, calming effect on him. He is not content and expressionless like his brother on the boat. Instead, he peers at me as he tries out ideas, turning them over meticulously. Even when we sit perfectly still and quiet at the far end of the lake, it’s with intensity that we listen to the bullfrogs and crickets serenade us.

When Cartter expresses concern about the Hemlocks he sees dying, I tell him, “One day soon they’ll all be gone,” and then I explain that there’s an invasive Asian beetle, the Wooly Adelgid, that has infested the forest and is killing the giant conifers that dominate it.

This information does not wash over Cartter as my burial wishes did his brother. Rather, it pierces him, and gives rise to a long series of questions: “Is there another beetle that can protect the trees?” “How did the Asian beetle get here?” “Did people bring it on purpose?” “What part of the tree does it eat?” “Why does eating that part kill the tree?” Finally, the closest he can come to accepting the Hemlocks’ fate is with a plaintive hypothetical. Turning back to his rod and reel and taking aim, he says, “Too bad they don’t kill poison ivy for us,” and resumes casting his lure, watching for a fish to break and present a target ringed in concentric ripples. The world is Cartter’s dartboard, and he in turn is its bullseye.

A week in the summer, a weekend in the fall, that’s how much time I’ve spent in Sapphire for most of my forty years. There were more frequent duck-ins when I was a Clemson undergraduate, a summer spent interning for the nearby Crossroads Chronicle, and a memorable two weeks visiting my dad and commuting to morning class leading up to my final semester. I’ll round a bend on the trail, and the smell of the forest will bring those times back for an instant before a breeze carries them away again. Time is heavier on the Upper Lake, though, memories not so easily swept away. Normally, when a trip ends and I have to head home, I’ll take one last walk up to the boathouse. I’ll stick my head inside for a peek and then walk around to the deck on the far side and look up towards Sassafras, like JTL I, reluctant to leave. There’s a stillness that hangs around me like a picture in those moments, a sweetness to the air that part of me can’t let go of. Thinking of that spot on the lake, I can sense it all so clearly in my mind that it’s as if I’ve spent half my life there. Yet another of the water’s tricks.