I remember participating in two graduation ceremonies in my life – high school and college, and I disliked both. Walking across the stage in high school, I felt awkward and unsure of how quickly to move and of what to do with my hands. Four years later I was an insignificant speck amid a sea of Clemson graduates in Littlejohn Coliseum, and my divorced parents were both in town to watch. After grad school, I skipped the ceremony.

People seem to be observing a lot more graduations these days. There are signs in my neighbors’ yards proudly proclaiming kids’ “graduations” from fifth or eighth grade. I had to sign a card for my nephew for graduating fourth. Our schools’ performance may be deteriorating in some respects, but their sense of self-importance certainly isn’t. Formerly unheralded milestones are now major achievements that merit large ceremonious gatherings, diplomas, and public announcements displayed like campaign ads. When I come across such pomp and circumstance regarding apparently minor accomplishments, my initial reaction is to think that we’ve lowered the bar, that someone needs to tell these kids, their parents, and the schools, “Get over it. You ain’t done anything yet.” Then I went to kindergarten graduation.

I was ashamed to admit to people the reason I was going to miss the season’s first summer league swim meet after three years of being the head coach and de facto meet coordinator. I even flirted with pushing the meet on Scotty, but when Danyelle suggested it to him, he panicked. “He’s really excited,” she said, so I told people that I was going to “a graduation,” or “my kid’s school play.” In conversations that drug on, though, the whole truth rose to the surface – I was leaving the team to its own devices, because my son was getting a diploma for the academic equivalent of getting out of bed. “You can’t believe what a big deal those things are,” one mom said.

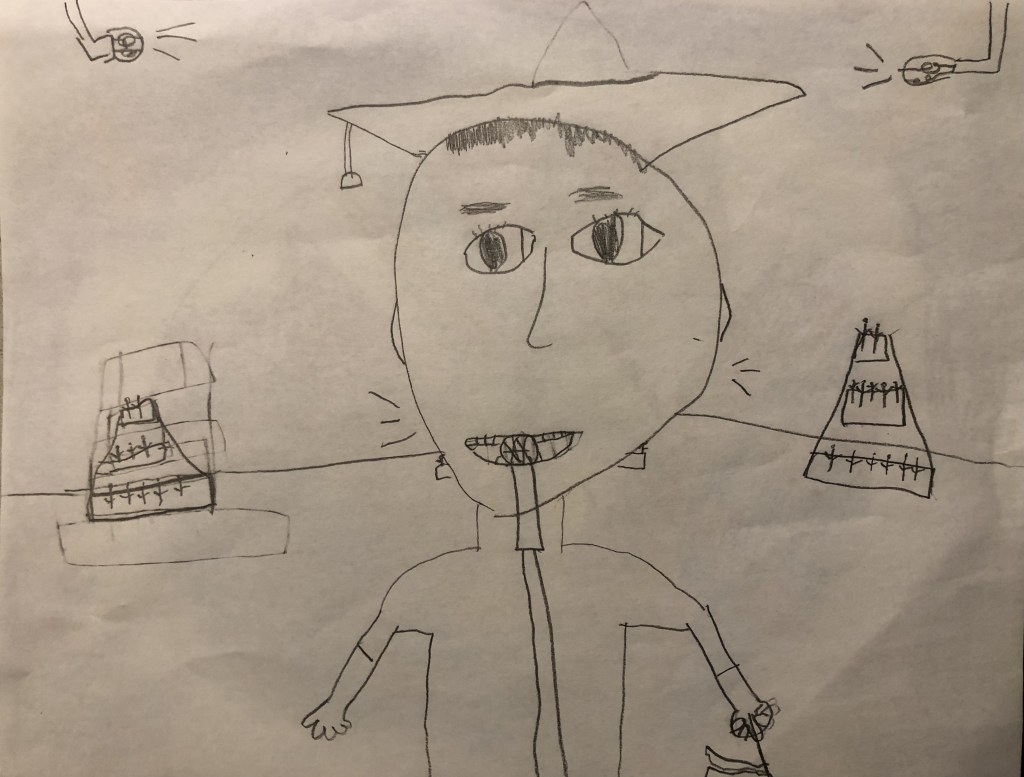

She was right – I couldn’t, but it started dawning on me when Danyelle told me to take a closer look at the picture Scotty drew the night before the event. At first glance it looked like a crude self-portrait, a boy’s face front and center taking up much of the page, smiling, big eyes and eyelashes, clearly Scotty. After a mental zoom out, though, I realized he was wearing a mortarboard and standing in front of a microphone. There were bleachers behind him for the other graduates, lights shining above him, and little lines coming from his mouth to indicate that he was speaking. Clearly, the swim meet was not on Scotty’s mind. The picture was a perfect window into his apparent use of what sports psychologists refer to as “visualization,” a tool I was never so adept at using. With his prematurely advanced meditation skills, Scotty had produced a strong signal regarding the occasion’s importance, but still, I had my doubts.

I couldn’t let go of the thought that I was bailing on people who needed me, and that kindergarten graduation was a weak excuse. At our pizza dinner just before the ceremony, I chided Scotty that I was letting down a lot of people to be there with him after he wanted no part of the thoughtful note that I’d written in his card. The tears were quick to flow, and after regrouping, I tried to start up a conversation about getting to see all his classmates together one more time. At that point he looked me in the eye and let me know plainly that he “really didn’t want to talk right now.” I wish I were as emotionally competent. At six, Scotty already understands how to tell people to fuck off in exactly the right way at exactly the right moment. It’s a skill that’s eluded me my entire life, and being on the receiving end of it illuminated just how useful it would be. With one calm, assertive sentence, Scotty successfully turned a shrink ray on my ego, and kindergarten graduation suddenly seemed much bigger.

Shortly after our arrival at Scotty’s school, though, I discovered to my shock and dismay that I still hadn’t fully grasped kindergarten graduation’s momentousness. At kindergarten graduation 20 minutes early is late. “These seats are saved,” people said as we snaked through the rows of fold out chairs. One guy was saving ten seats. I was beginning to feel like Forrest Gump boarding the school bus for the first time before we finally found three seats in the back row. Ten minutes before showtime, the little auditorium was bursting at the seams, and I wondered how I could have forgotten what a brouhaha this event was. Was it possible that this production’s popularity had exploded in the two years since Cartter was in it? Was that year’s edition less well attended because people were still covid-scared then? Maybe because Cartter was less openly enthusiastic about the show, I disregarded the hubbub, made a mental bubble around myself, and just looked forward to getting out, or maybe, even after witnessing Scotty’s drawing and being schooled by him at dinner, I still couldn’t shake the idea that kindergarten graduation is ridiculous.

“Cherish these memories,” the principal said at the show’s outset. The little children sang all their tunes off key, danced out of step, and delivered their lines with varying degrees of intelligibility. The adults in the audience laughed adoringly and videotaped with their phones. All as you would expect. Cartter craned his neck, desperate to keep his eyes on his little brother. Listening to him repeatedly comment at the start of each song, I couldn’t help but tease a little.

“What’s next?” I asked him.

“I don’t know,” he said leaning in close. “But I remember the songs.”

Two years ago, Scotty stood on a chair and watched his brother in the same show. I didn’t film any of it, but as Cartter stood next to me and relived his kindergarten glory days, I realized, “I want to remember some of these songs too,” so unlike two years ago, I pulled out my phone and started recording. Scotty stood in front of the mic wearing a Hawaiian shirt he picked out and smiled a slight, attention-loving smile while he delivered his line, “I can spell blue, B-L-U-E. I can say it in French. Bleu.” He waved his blue ribbon at the right time while the kids sang “I Can Sing a Rainbow,” and I didn’t care anymore about whether I was being ridiculous. I was like all the other doting parents and grandparents, reveling in the precious fleeting moment that is kindergarten graduation.