I’m trying to teach Cartter respect. He whines too much. He argues. Sometimes, when a new adult speaks to him, he squints and contorts his eyebrows and upper lip so that he looks like a blond, incredulous David Schwimmer. It’s the kind of look that says, “Do you see what you’re doing to my face? I can’t believe you’re making me do this stupid face.”

I find myself sounding like my dad – “Look people in the eye when they talk to you;” “Say yes, sir and yes, ma’am;” “Answer them when they ask you a question.” When I was a kid, I never thought I’d be repeating these commands. The concern behind them seemed so superficial, and I thought I’d remain above it into my adulthood. Now, I realize, “Oh my God. How many people did I do the Schwimmer face to?” and I have an intense desire for my son to avoid people’s disgust. For both of us.

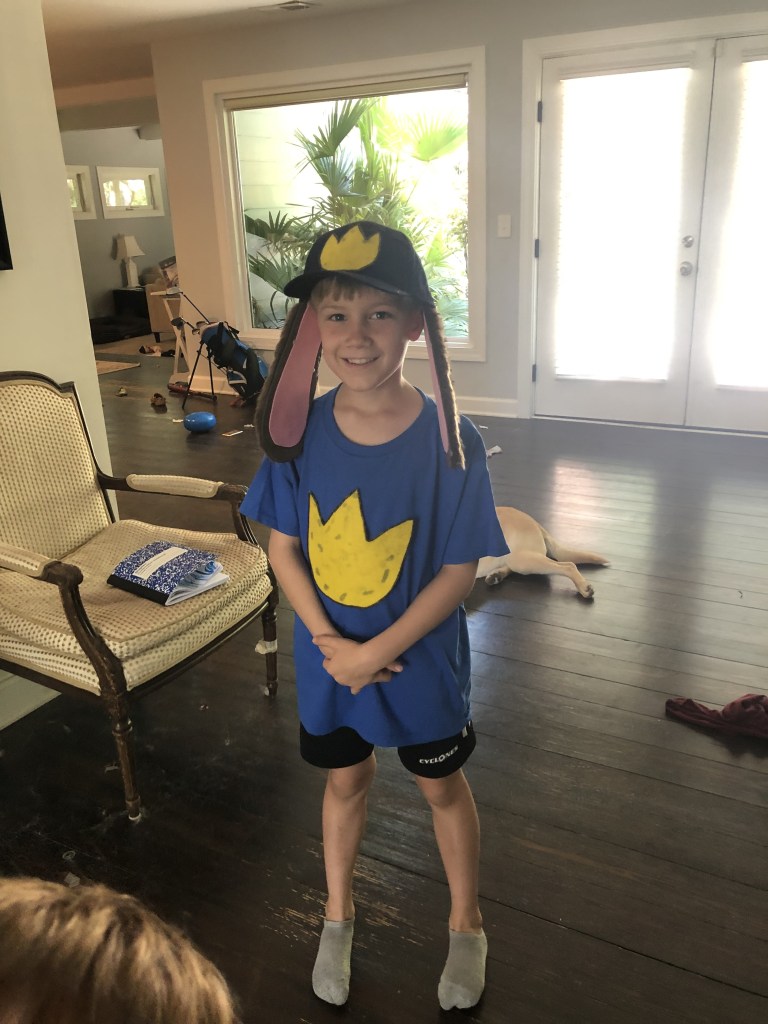

I’m ashamed and disappointed that I’ve failed Cartter in this way, that with me as his father, he’s reached the age of seven and a half not knowing that acting like David Schwimmer from the T.V. series Friends makes you a douche. A more committed dad would have been teaching Cartter proper manners as soon as he was off the tit, back when he was insisting that he be allowed to hold the vacuum cleaner nozzle while he ate in his highchair. Not me, though. I was just glad when the forty-five-minute struggle ended, most of the bread balls and mashed up vegetable matter were gone, and I could finally release him and clean up his mess. Now, because of my laziness, Cartter entertains himself at the dinner table by affecting his voice in all manner of ways while he recites the name Larry over and over again. His favorite is slow motion K hole Larry with chicken in mouth. It brings him to near pee pants level hysteria, and it brings my open palm slamming down on the table in anger and frustration.

Maybe browbeating is the answer, constant harping, shows of force. I just don’t want to do it, though. As embarrassing and awful as the Schwimmer face is, hammering it into something more acceptable doesn’t seem worth it – “Chew with your mouth closed;” “Don’t talk with your mouth full;” “Don’t belch at the table.” I can convince Cartter to cover up his chewed-up-broccoli grin long enough for him to hang his head and manage an “Okay,” but his laughter is barely subdued, and I can see him thinking the exact thought I had at his age: “Why do you care?” Hammering more forcefully does nothing to help him answer that question.

Certainly, my vanity is part of the reason I care. If your kid has ever made Schwimmer face at someone, and you’ve found yourself mirroring the recipient’s reflexive eyeroll, you know what I’m talking about. My sanity is a consideration too. Cartter’s disrespect is maddening at times. I can take only so many K hole Larries before my brain breaks and sends my forearm crashing down on the dining room table with enough force to bring the integrity of my ulna into question. Apart from my own selfishness, though, I just don’t want my son to be misunderstood. I want him to be free to share the brilliant child behind the Schwimmer mask, not just because it will make me look good, but because it will make his life better.

When we’re at his brother’s kindergarten graduation and the old man sitting next to me wants to talk, Cartter’s eyes flash as he thinks out loud and responds with confidence. Sure, he makes mistakes. He says, “yeah,” when he should say “yes, sir,” and he misunderstands one of the old man’s questions, but he’s freewheeling, and the intelligence shining from within him is undeniable. He’s like the kids who made me fall in love with coaching in my twenties, the ones that make you laugh and go, “Wow.” Then, after the show, when a friend’s dad is a little too enthusiastic with a line of questioning, the clouds gather in his eyes, and he looks away as his shoulders move toward his ears and Schwimmer threatens. It hurts to watch, and it would probably help if I could say to him, “Cartter, remember your manners.”

Of course, manners, like most everything else are only useful in moderation. I’ve coached kids who compulsively filled any brief pause in my speech with the words “yes, sir.” For these children those were the magic words that voided the obligation to listen and ended conversations with their daddies, thereby freeing them up to go on doing whatever they wanted. Cartter feeding me bullshit “yes sirs” would be even worse than him peeing his pants over K hole Larry at the dinner table, more grotesque, like a Schwimmer face full of Botox. “We can be informal,” I tell him.

“What does that mean?”

“It means you don’t have to call me sir, but you still have to show respect.” And there you have it, my number one means of teaching my kid about respect: telling him to show respect.

It’s the type of thing I used to tell assistant swim coaches not to do. If a young group isn’t performing a skill correctly, continuing to tell them to do it correctly probably isn’t the answer. Take a step back; look at what they’re doing; consider the gap between where they are and where you want them to be; then, address it. Don’t heap blame on them; direct it at yourself. Never ask a kid, “What are you doing?” in anger; they probably don’t know. Finally, smile a lot. That really seems to help. Basically, if you want the kids to respect you, learn how to respect them.

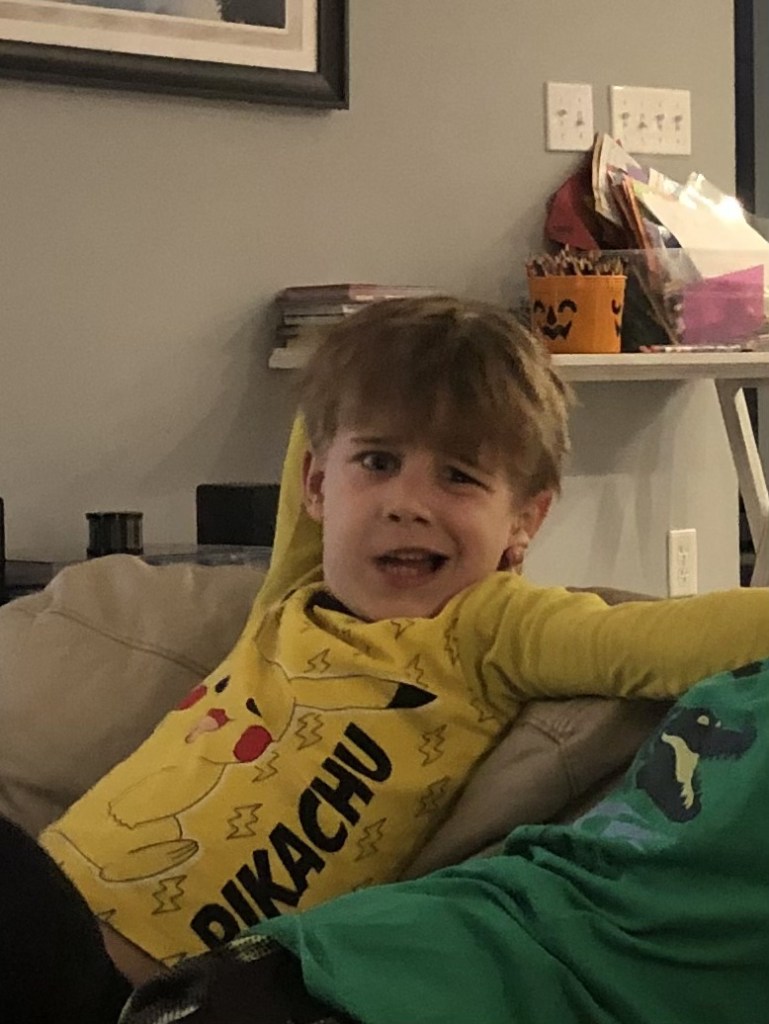

As I write these words, Cartter is outside watering the flowers he and his brother planted. There’s a pitiful little patch of green sprouting up where they buried the seeds, and he’s using a squirt bottle to be delicate. When I ask him about it, he’ll tell me about why he picked the spot, how he and his brother tilled the earth, and how some of his classmates’ flowers died. He’ll be calm, and he’ll lock eyes with me, his expression one that asks, “Are you still interested?” I am. It’s the best tool I have at my disposal in this quest to teach my son respect – genuine interest in the boy.

My interest lets me give him the lead. It helps me guide with a light touch. It brings me joy and gives him confidence. “Point out what they’re doing well,” I used to tell assistant coaches. “Be excited about it.” Nobody wants to have to listen to someone tell them they’re fucking up over and over again. If you want to see a kid’s true self, if you want them to respect you, the first thing you have to do is wipe the Schwimmer off your face.