COLONOSCOPY. The word itself stirs up butterflies in my stomach and makes my palms sweat. A younger me disbelieved the day would ever come when I would willingly give myself diarrhea and let a stranger snake a camera up my ass, but as of this moment, it seems that’s where my life has been headed all along.

I’m addressing my GI symptoms like Danyelle and I have addressed making home repairs: in a nonsensical, inefficient order: First replace the siding and repaint; then do it all over again when the next contractor comes along and finds rot. See one doctor for upper GI symptoms, and schedule an endoscopy; see another on the other side of town for lower GI symptoms and schedule a colonoscopy. The redundancy and what it says about my intelligence is frustrating in each domain –my home and my health. The difference is that whereas a competent general contractor could probably help us avoid mishandling home improvement projects, I’m not so sure such experts exist in the medical field. In my experience doctors are a lot more like the window company that leaves you with an unfinished wall in your living room than they are like an expert homebuilder. They’re narrowly focused. The ones who like to play expert are particularly irritating and potentially dangerous. Even good doctors and homebuilders, though, start out with lots of questions, and their investigatory nature (combined with their ability to bill) drives them to do things no ordinary human would ever want to do, like plumb the hidden depths of crawl spaces and anuses, hence my fear and distrust of them.

This eagerness to explore the unknown in the name of amassing riches makes doctors kind of like pirates. The thought of accepting a drug and surrendering my lifeless body to one of these creatures so that they can search for abnormalities horrifies me. Just how deformed is my asshole as assholes go? Will the prep and procedure be painful? Am I going to be able to handle myself and not act like a fool? These are some of the questions buzzing around just below my consciousness that arouse anxiety, and then of course, underneath those superficial concerns lurk more sinister beasts like, Will they find some kind of nightmare affliction that necessitates even more invasive surgery? What could that do to my life? And then, still deeper, What if it kills me?

Nights are the worst. In the dark with nothing to distract me from my thoughts, it’s like I’m a kid again, lying awake nervous about a swim meet, trying to deny that some future self will be in the exact situation that fills my present self with dread. Most people say a colonoscopy is nothing to worry about, that the anesthesia makes it completely tolerable, kind of a non-experience, but in my mind, of all the disgusting things about the prospect of reversing the flow of anal traffic, anesthesia is high on the list. So high, in fact, that I plan to forego anesthesia altogether.

The endoscopy and my fear of death drove me to this decision. I thought I handled myself well at the outpatient procedure clinic that day. I swallowed my anxiety and exchanged pleasantries with all the staff members, eventually watching as the anesthesiologist pumped a dose of clear liquid from a very large syringe into my IV port and then commenting, “Whoa, that stuff works fast,” as it rushed to my brain and thumped it to sleep. A few hours later, I sat at my house shivering, looking at a thermometer that read 93.8 F and then, thinking the device was broken, a second thermometer that read 93.8 F. I spent the rest of the day wrapped in blankets, wearing wool socks and a beanie, struggling to void my bladder and feeling my heart flutter inside my chest. My temperature stayed below 97 all day. I drank hot tea and soup while I distracted myself with the TV, scared I was going to end up in the ER. You know how people have a certain liquor that they steer clear of? Mine’s propofol now.

When I call up the GI clinic and let them know about my decision, I can tell the nurse on the other end of the phone isn’t too wild about it. I met her about a week prior, a big lady with tattoos up and down her arm. She had an easy time talking about bowel habits and symptoms and seemed to genuinely like me when I was sitting in the little exam room being relaxed and open with her. After a little phone tag and my proposal to break with normal procedure, though, I can tell she’s put out. I can be awake, but she wouldn’t advise it. Why not? “Because you’ll be uncomfortable.”

Avoiding discomfort doesn’t seem like a good reason to take a drug that gives me hypothermia and heart palpitations, so before hanging up, I thank the nurse sincerely. She’s given me slightly more confidence to skip the anesthesia and thereby cross death by propofol off the list of things to worry about.

Of course, all my other concerns remain, but buoyed by this unusual moment of clarity, I make another decision that lifts my spirits even further: I’m going to make an experiment out of this. Why should the doctors have all the fun? I’m going to observe myself and others in the days leading up to and including the colonoscopy, and I’m going to write down what I see. Instead of getting a colonoscopy, it will be like I’m watching myself get a colonoscopy, and if I remember that’s what I’m doing, then I’ll be more able to handle myself in a dignified manner. I’ll have a dignified colonoscopy! One that includes a firm but friendly refusal of drugs and a stoic demeanor while getting plumbed. I love this idea. I feel like a weight’s been lifted, and I’m ready to get to work. First order of business: call my dad.

Besides being more preoccupied with his bowel habits than anyone I’ve ever known, Dad’s proctological bona fides include a colonoscopy sans anesthesia. Plus, he’s really good at phone conversations. It’s the most natural place I could begin my experiment.

Turns out Dad didn’t exactly go without anesthesia. He was on some kind of drip, and when he started groaning in pain, the doctor gave him a little extra, and the next thing Dad knew, he was waking up, and the whole thing was over. This all happened in a GP’s office, i.e., there was no anesthesiologist and no GI specialist, but there was a general practitioner with drugs and a scope that he guided up Dad’s ass. Dad’s second colonoscopy came after a botched Cologuard attempt and included all the usual trappings, like an anesthesiologist who administers drugs. Dad’s advice is to avoid colonoscopies. He says the second one he had left him sore for a week, like he’d done a thousand sit-ups after years of not working out. He paints a picture of a guy who performs 15 colonoscopies a day, casually ripping his way through people’s insides. It would all be more unsettling if Dad weren’t slightly prone to dramatics.

There are two stories that perhaps best typify the Dad Drama. One is a sinus infection that ultimately resolved when Dad was working in a humid warehouse, sneezed, and pulled out a three-foot booger that threatened to take one side of his face through his nostril. The other is a 17-day constipation episode in Paris that ended with his first ever espresso and a small cannon ball being passed into a kind of pseudo toilet that was basically a hole in the floor with some foot pedals in front of it. I like how the stories’ hero endures a period of suffering that culminates in brief but intense agony followed by instantaneous relief. My own suffering never seems to meet such an end. Instead, I wind up having a discussion with a doctor about “managing” and “lifestyle.” Chronic sinusitis, swimmer’s shoulder, scoliosis pain; these things seem to be with me for the long haul. There will be no magic booger whose extrication changes everything.

The phone conversation with Dad isn’t exactly encouraging. Both his colonoscopies included anesthesia, and neither had a hero’s ending. Instead, there was disorientation after one and prolonged pain after the other. Still, I’m not discouraged. Sure, these new stories lack the usual heroic triumph while retaining all the dramatic suffering, but ultimately, Dad’s never had a colonoscopy without anesthesia, so he doesn’t really know what it’s like. Maybe this is my chance to one-up him, to finally have my own heroic Dad tale that ends with sweet relief. Or with pain and embarrassment. Who knows?

There’s something freeing about having a plan for how to behave even though I don’t know what’s going to happen. The ancients called this approach to the world amor fati or love of fate, and the realization of it is like nature’s sedative for that nagging worried part of my psyche. I don’t know what sort of pain I’ll go through or what the outcome will be, but I do know how I intend to act, i.e., with acceptance, and the only way to make good on that intention is to start practicing right now.

After a rare perfect night’s sleep, I wake up resolved to pay close attention to my thoughts and behavior. I have two more days before I start the prep and thereby kick off the entire colonoscopy ordeal. I’ll keep my notebook handy, and I’ll avoid distraction. Reading is ok, because it requires me to operate my mental machinery from the driver’s seat of my mind, allowing me to note where my thoughts go when my focus slips, not like TV and radio. TV and radio take me out of the driver’s seat, numbing my awareness with flashing lights and loud noises and allowing subconscious concerns to fly around unnoticed and unchecked. Along with social media, TV and radio are basically the anesthesia of modern everyday life.

I decide that saying no to anesthesia and practicing amor fati means not listening to the radio when I’m driving around town. I had an English teacher in high school who said blasting your car stereo all the time was a sign of foolishness. “I can be alone with my thoughts,” he said. “I’m not a mental weakling.” He also said he could make his morning commute to school while doing the crossword and driving with his knees. He was the best teacher I ever had, and I think of him in the moments when I catch myself instinctively reaching for the stereo’s power button just as boredom starts to give way to anxiety, my internal autopilot craving the distraction of NPR or Fox Sports Radio, of smug idealists and meathead former frat boys talking loudly, of a guy in Goose Creek who wants to see ya in a Kia, of noise. “I’m not a mental weakling,” I tell the impulse. “I’m paying attention.”

I drive in silence to the barber shop where I force myself to converse with the brash young woman cutting my hair. I drive in silence to the dentist’s office where I avoid talking with the irritating hygienist who recommends flossing three times a day and wants to bond over growing up on Sullivan’s Island. The thought of saying, “Oh, I grew up there too!” is like the tendency to sit silently in the barber’s chair or to automatically turn on the radio. I don’t give in to it, because right now my life is a dress rehearsal for the coming moment when I refuse anesthesia face to face and avoid complaining while a grown man sticks an 8-foot hose up my butt. If I can’t manage these more mildly awkward situations in a way that I truly choose, how will I handle the real thing? Being uncomfortable is inevitable. Losing control of myself doesn’t have to be.

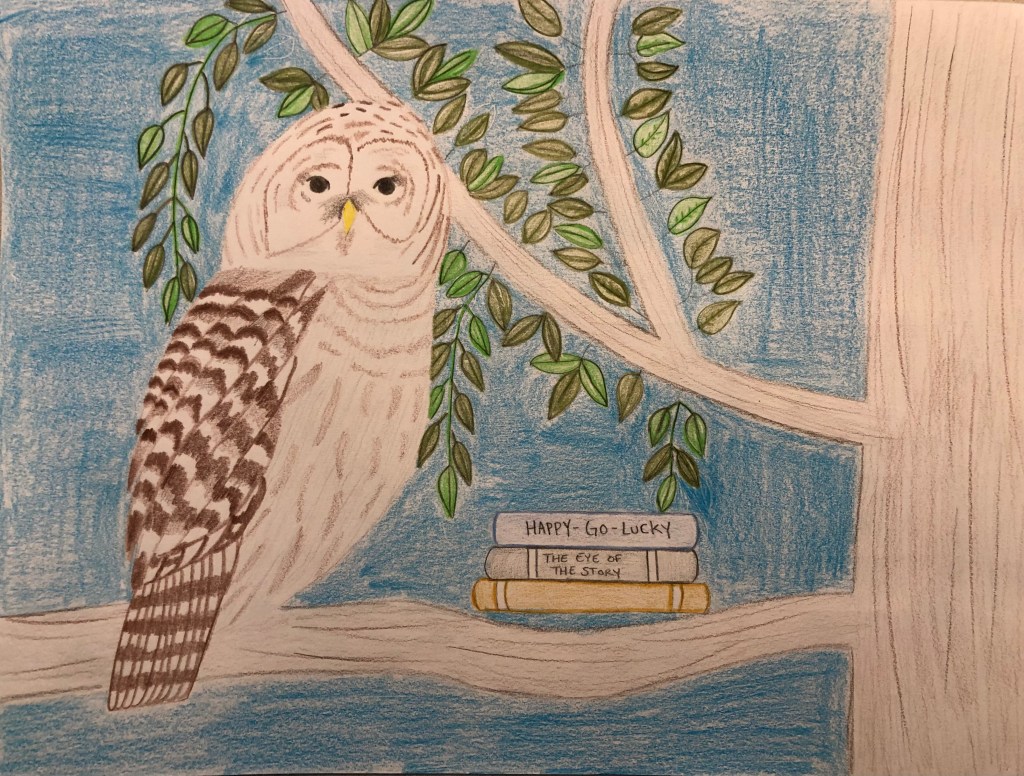

Maybe it doesn’t sound fun, turning life into play practice for a live on-air colonoscopy production, but fun is overrated. Forcing myself to accept my fate, to pay attention, and to act accordingly has a pleasurable side that far eclipses “fun.” I notice the blossoms forming on our citrus trees. I look up and see a Barred Owl on a limb hanging over our street. I realize that the library section I’m standing in is the memoirs section. I expected none of this. In the case of the library, I even intended otherwise, yet a seemingly very unlikely series of detours landed me exactly where I didn’t know I wanted to be. It’s the feeling of seeing for the first time something that’s been right in front of you all along and wondering, “Where have I been?”

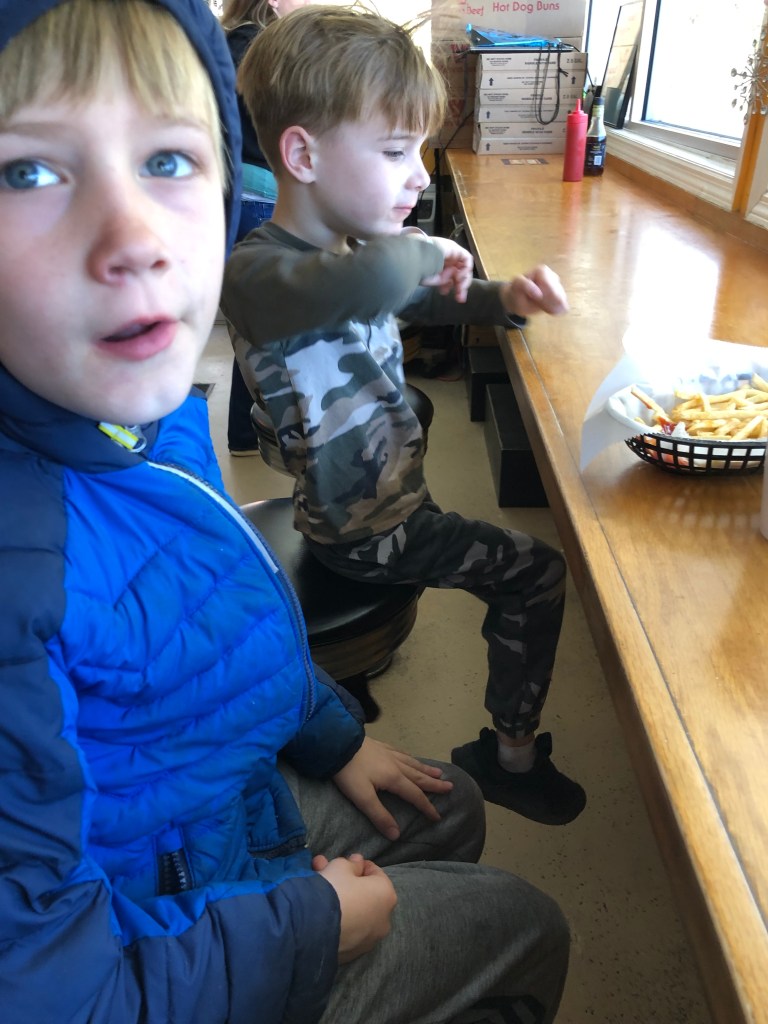

Kids are great at eliciting that feeling. It’s a big reason why I’m so greedy about my time with the boys. On Wednesday afternoon, walking the dog with Cartter, there’s no mental room to be worried while I’m fielding questions about tomorrow’s big fast. “Nothing?” he says. “Breakfast?” No. “Lunch?” No. “Dinner?” No. He pauses for a second and looks up again with hope and mischief in his eyes, “Snacks?”

“Nothing,” I tell him. “Just juice and broth.”

“Do you like that?” he asks. He’s holding Sammy’s leash, and he does a little 180 degree hop to take a few steps facing backwards before hopping back around. We’re walking through the HOA park, and he starts identifying the backs of houses by saying which dogs live in them.

“Remember those dogs we call piggy dogs that always bark at us?” he says. “Remember? Remember?” My mind drifted for a minute. “They live there.” In that moment it hits me just how attached I’ve gotten to our neighborhood and that our oft flooded crawlspace is perhaps a small price to pay for the life we live here.

I think if I could have Cartter with me in the operating room that it’d be a big help. If he were there, I’d have no choice but to man up completely, to focus on the bright side even. Plus, he’d probably ask lots of great questions about the live video footage of my colon. It would definitely take some of the focus off of me. As nice as it sounds, though, bringing my seven-year-old into the OR is about as reasonable as performing a solo colonoscopy while driving in crosstown traffic with the car stereo on full blast.

That reality fully sinks in once the boys are in bed later that night, and I tell Danyelle that part of me wishes I could skip ahead and get this thing over with. Not straight to the other side of the procedure, mind you. That would be like failing. It’s the waiting I want to skip, the growing tension. It’s the kind of thinking that used to make me throw up the night before swim meets as a kid, scared of being scared as much as I was preoccupied with the pain that would come with swimming the mile. It wasn’t just that my future self was going to be in exactly the place I didn’t want to be – standing atop the blocks about to dive in and punish himself for 17 minutes – That was part of it, but there was also the knowledge that by caving to my anxiety, by failing to sleep and vomiting instead, I could make things even worse for that future me, that by being afraid of losing self-control, I’d inevitably lose self-control.

I was always most afraid of the mile. Spanning 66 25-yard laps or three 500’s with a 150-yard kicker at the end, it is by far and away the most grueling event in swimming, and it requires bookoo self-control. When you finally hit the water for the mile, there’s a mixture of relief and dread; relief that the waiting is finally over, and the real test has begun; dread that the pain is going to build from this point on. Colonoscopy prep is like that. The beginning is no problem. Fasting is easy. I can quell my hunger by simply accepting it. By mid-afternoon on Thursday, I don’t even notice being hungry anymore. Still, the cleanse and the scope loom in the foreground like the second and third 500’s of the mile.

I start the Gatorade solution at 7 p.m., remembering how as a kid I’d watched my dad look like a scared animal as he went back and forth to the toilet in between chugs from a gallon jug. By 10 p.m., though, I’ve had eight watery dumps, and I start to think that I might be as good at diarrhea as I am at not eating. Then I drink the second half of the solution, and at BM20 around 12:45 a.m., I’m ready to be done. When BM30 strikes at eight the next morning, I’m a little worried. Is this ever going to stop?

By the time you finish the second 500 in the mile, the pain is getting intense, and you have a choice to make – slow down or break through. By the time I get to the procedure clinic, I’ve lost six percent of my body weight in 24 hours; my mind is dulled to the point that I forgot to bring my wallet; and I have to make it through a mini gauntlet of nurses who have no idea that I’m choosing to forego anesthesia. “Well, maybe just sign anyway in case you change your mind,” the first one says. I oblige although I have no intention of changing my mind. This is what I’ve been training for.

When the doctor finally comes in, I’m half expecting him to put on the full court press like an irritating dental hygienist who wants you to get X-rays. It’s been three years. You’re going to be uncomfortable. Instead, he says he does one or two of these without anesthesia a month and that it’s usually fine. He’s a fit, slightly built man in his fifties. He looks like Pinocchio became a real boy and then grew up. I can tell the nurses like him.

“Just let us know if it hurts too much, and we’ll stop,” he says.

“I’ll try and bear it,” I say.

“Just let us know,” he says again. Then, as he’s about to walk past the curtain, he turns around to add cheerily, “You get to play DJ since you’re staying with us! What do you want to listen to?”

“I don’t care. Whatever you guys want.”

“You sure? I have a pretty wide-reaching playlist . . .”

Danyelle is grinning in the chair beside me. She likes this guy too. “He likes jazz,” she says.

“Jazz?”

“No, I don’t wanna . . . Really . . . You guys play whatever you want.”

His eyes go back to Danyelle, who’s almost laughing and says again, “He likes jazz.”

“Alright!” he says flinging open the curtain. “Let’s jazz it up!”

I thought that anything I listened to would be tainted forever, but I was wrong. I’m not sure quite what the renditions are, but when the nurse wheels me into the procedure room, the Thelonius Monk tunes floating around in the air are exactly the quirky welcome I never thought possible, and they actually help me relax.

Getting a colonoscopy ends up being kind of like a big reverse shit. Definitely nowhere near as awful as the finishing stretch of the mile. The doc talks to me throughout. It’s the first weekend of March Madness, and he says it’s better than Christmas morning; he asks about my kids and where they go to school; and of course, he tells me what he’s looking at – nothing out of the ordinary, except . . . “This is the cleanest Gatorade prep I’ve ever seen! Whad’you do?” At one point I’m afraid that I’m about to shit on him, and as if reading my mind, he says, “If you need to pass gas or anything, feel free. There’s nothing down there.” When it’s all over, and the nurse is about to wheel me away, I say I’m glad to be done, and then he stops putting away his instruments behind me and says, “Oh wait. There’s one more thing I forgot to check.” The guy really seems to enjoy performing colonoscopies.

“Did you know how tough he is?” he says back in the ready room with Danyelle. I know he’s joking around. I’m not that tough. I just had a colonoscopy because of a really bad case of hemorrhoids. Still, I let myself be flattered. “Most people can handle it,” he says turning to face me and lowering his voice a little. “We just have to expect the worst.”

I understand “the worst” to mean a patient having a psychotic episodemid procedure. It would really cut into the practice’s ability to operate if everyone who underwent a colonoscopy turned into the girl from The Exorcist the instant the scope went up their ass. Even one exorcism a week would probably be a significant setback. I could have been that person. Instead, I think I was something of a relief for this guy, and it wasn’t because I expected the worst. I expected the best, not from the procedure, the experience of which was unknowable to me just a short while ago, but from myself. I believe it was Forrest Gump who famously said, “Life is like a colonoscopy. You never know what you’re gonna get.”