Recently, we let our kids watch their first PG-13 movie. We were on a rare family trip that necessitated staying in a hotel, and Mrs. Doubtfire was on TV. “What the heck?” I thought, “I saw it when I was a kid.” I was entertained by Robin Williams’ performance back then, and I still am. Watching it as an adult, though, in the aftermath of the actor’s suicide, I’m also disturbed by the cloying neediness of it, the pathetic lengths that the character will go to in order to be near his kids. In one scene he gives a misty-eyed defense during a custody hearing and whines to the judge that, “I’m addicted to my children, sir.” It disgusts me, this comparison of fatherhood to addiction, the idea that being a dad is like being a junkie desperate to score his next hit of smack, and yet I wonder, am I any better?

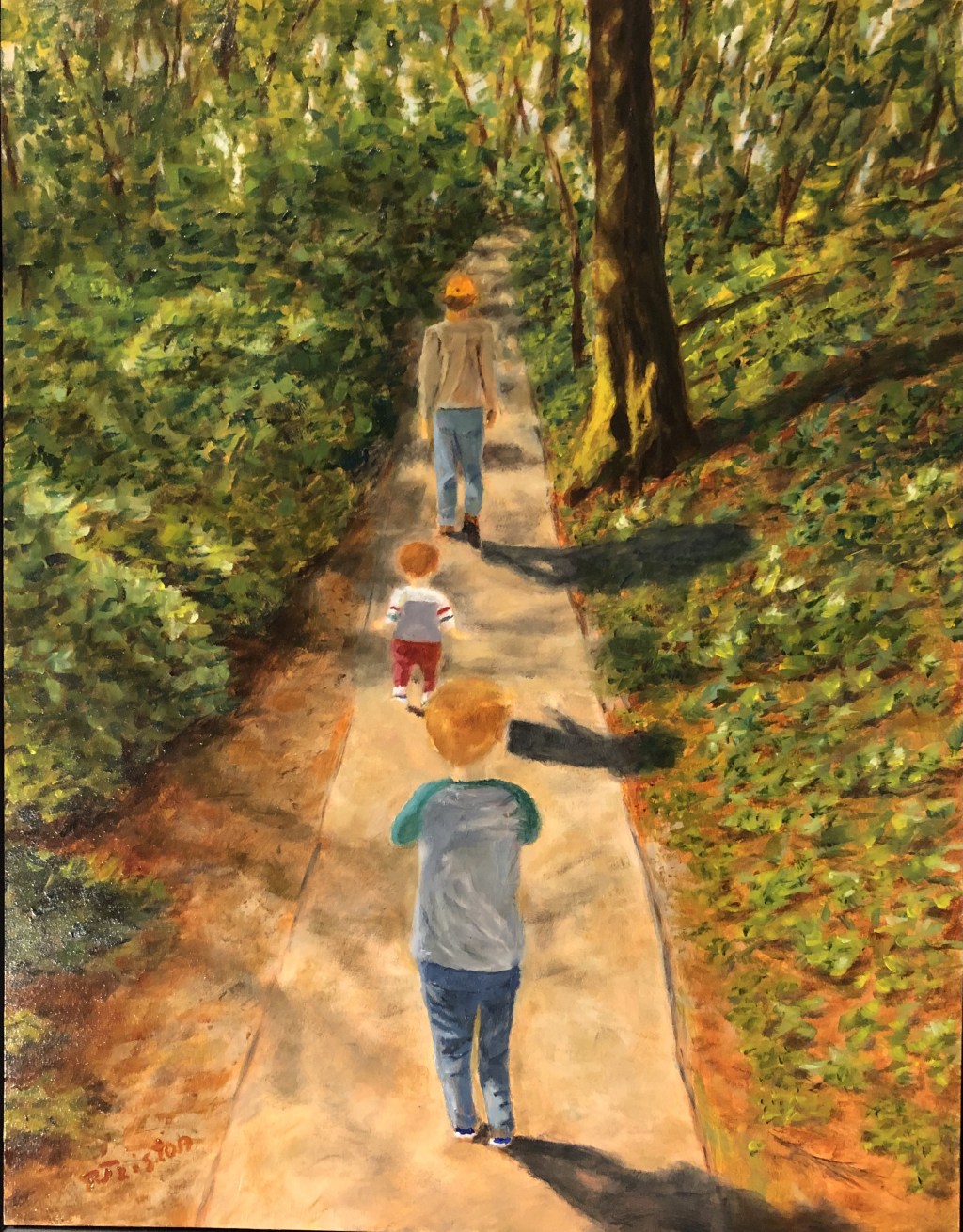

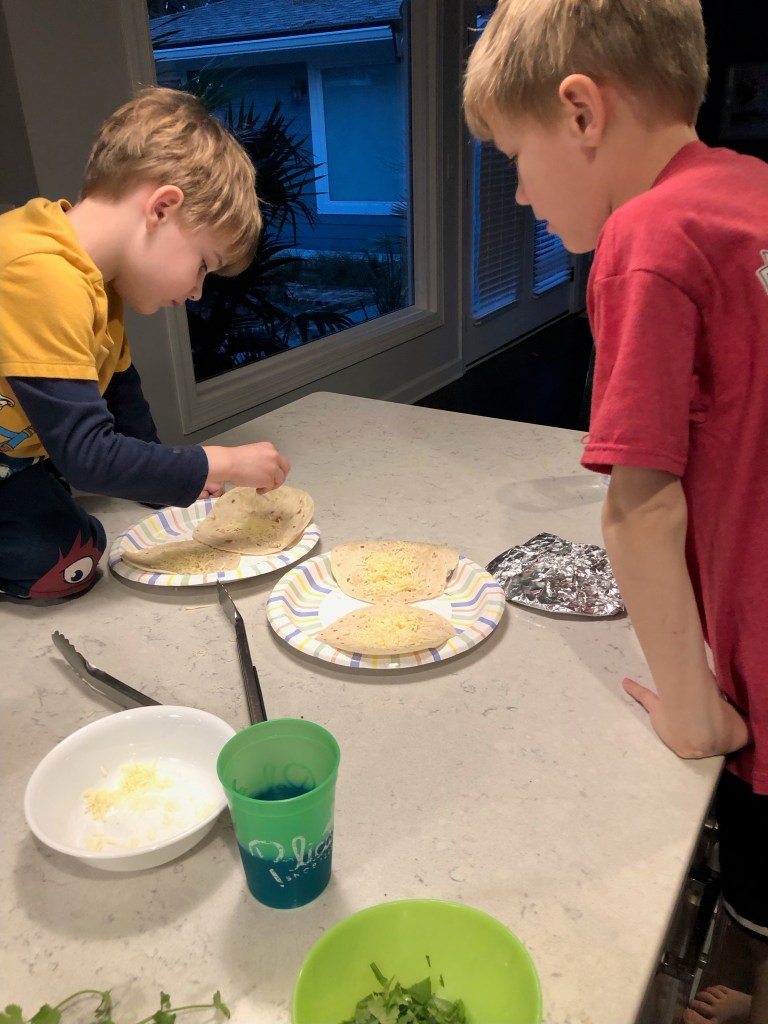

These days the kids are like my ticket to life. Small acts like driving through Wendy’s are imbued with a sense of purpose that calls me to attention and sends me to my keyboard to record what I learn. Walking down the street with one or both boys in tow, I’m a more sympathetic character, to passersby and to myself. The kids necessitate little things like playing cards, going to the grocery, and driving across town to school, and in doing so they make those little things better. Sometimes, my contentment with the ordinary is so powerful that I’m compelled to say something like, “I like doing this with you.” Sure, the brothers’ current level of need is enough to drive me crazy a good portion of the time, particularly when it manifests as screaming fights that distract me from writing about how undistracted they make me, but if they were suddenly ripped away, there’s a high likelihood that I could do worse than become an entertaining crossdressing nanny. Safe to say my sense of humor would suffer.

Thinking about such a sudden loss gives me a taste of the panicked denial that would surely accompany it. It’s not that I understand the lifelong grief the parent of a deceased child goes through. I don’t, but I can imagine its onset, and it’s like a cleaver to the sternum. I have a harder time getting a sense of something much more likely: the kids’ gradually increasing independence and the corresponding decrease in my own usefulness. Maybe I just don’t want to, because the predictability of the boys growing up implies some responsibility on my part to prepare. Responsibility. Prepare. Sounds like something you’d want to put off, like responding to email requests for a meeting. At first glance procrastination seems more innocent than addiction, but if you’re staring helplessly into the void in your sweatpants after 20 years of parenthood, “I didn’t have time,” doesn’t quite resonate. After all, isn’t procrastination really secondary to indulgence? When Robin Williams’ character decided to dress up as a Scottish nanny, putting off getting a real job wasn’t his primary motivation. He wanted that good stuff, that sense of meaning that his kids gave him. I get that, hence my distaste.

The sound of my kids’ voices addressing me in all their sweet earnestness snaps me into reality like nothing else. The world around me slows down. The thoughts in my head are obedient, like vessels in a calm but crowded waterway, all under my command. When my kids reveal their curiosity and reach out to me for answers, everything feels so manageable, like I know what to do.

Between the two of them, my oldest is the more voluble with me for sure. He came into this world wanting to talk, and I’m the lucky soul who gets to be his sounding board. For now. He wasn’t even close to a year old the day he looked at me from his highchair and strained until his face turned red staring at the piece of food I held in my hand. I don’t remember what I was feeding him. I just remember how I felt seeing him make that face. I couldn’t believe it. He wanted so badly to say the word. He knew what it was. He just couldn’t will his mouth to make the sound. I was scared he was going to have a fit. I felt terrible that I was teaching him all these words and that he understood and was trapped inside himself.

His tongue loosened up soon enough, though. By 18 months he was talking nonstop. He referred to himself as “you,” because that’s what his mother and I called him. One time when we’d been at the house in Sapphire for a week, and Cartter’d had enough, he told us, “You don’t like Sapphire! You wanna go home! Charge those batteries!” We came home that day so that he could plug in under the covers in his own bed.

I’ve enjoyed all the idiosyncrasies of Cartter’s speech over the years – the poor grammar, the mispronunciations, the made-up words – but he dispenses with them nearly as soon as he picks them up, so eager is he to communicate on a higher level, which is fine by me. I’ll take our deepening bond over his waning adorableness any day. There is one childish habit, though, that I fear I’ll miss if and when it disappears.

I’m walking around the neighborhood with Cartter by my side when he lets go that magic word. It drifts between us as light as a feather. It’s one of those moments when the outer world stills, and I feel in complete control of the thoughts sailing around in my mind. Cartter has a question, and he wants my attention. “Daddy?” he says.

I love being Cartter’s and Scotty’s Daddy. It makes me feel like a warrior whose caress is as gentle as his blade is strong, or a philosopher whose teachings are as careful as his wisdom is vast. As “Daddy,” I can be a great man, but how long will it last?

It seems like I’ve been “Daddy” all my life at this point, even though it’s only been five or six years. Cartter started calling me by that name when he was still in the “you” phase – “You love Daddy.” I have a video of him when he was a little older. His brother is still in diapers, and the two of them are in the dining room bobbing up and down to the tune of “I Love You, Always Forever.” Cartter has a toothbrush in his mouth, and he says in his little three-year-old voice, “What’s this song about, Daddy?” It makes my eyes water every time.

“Dad” just doesn’t have the same magic. Dad is normal. Dad is fallible, mistake prone even. Dad can be a jerk. Try saying, “Fuck you, Dad.” Then try, “Fuck you, Daddy,” and you’ll get the difference between the two. At five, Scotty’s already tried out plain old Dad on me. He wore a wry grin when he did it, watching me closely to see how I’d react. I was surprised but careful not to give too much away. It didn’t stick.

My mom’s father has remained “Daddy” even with adult children. Mom refers to her parents as “Mother’n Daddy.” Her brothers and her sister do too. “Daddy” suits my grandfather even as an old man. He’s an old-fashioned Southern boy from Kentucky, though, and his kids inherited just enough of that nature and manner of speaking for the word not to sound too sissified rolling off their tongues. Whatever little bit of 1940’s Kentucky my kids and I got probably isn’t enough. I fear I’m destined to become just “Dad.”

Cartter will be eight in six months. A reasonable person would probably expect that my days as his Daddy are rapidly nearing an end, but walking alongside him in our neighborhood, waiting for his question, that assessment seems impossible. The thought of becoming something besides Daddy is as far away as the idea of my boy being suddenly taken from me. The waters in my mind are still, the vessels of my thought completely under control. I’d gladly don a fat suit and a wig and declare myself an addict in order to keep walking this road. All that matters is the question that Cartter is about to ask me, but when it comes, I’m suddenly a fool.

“Remember when you said that thing . . .” he says. I do. He wasn’t supposed to hear that thing. It was about the incompetence of an adult he knows and interacts with, and he’s confused about it. There’s a tiny moment of silence. A gust of wind interrupts the inner calm, and the vessels are pushed around and run into one another as I work to maintain outward composure. For a moment I think about defending myself. Then I remember who I’m talking to and what it feels like to be Daddy, and I go with just, “I was angry.” This, Cartter understands, and he tells me a story about when he was angry.

Maybe all this business about being called Daddy and my usefulness to the kids running out is purely sentimental. I like to fancy myself a philosopher parent, but if I were a character in a Platonic dialogue, most likely I’d be the ass overestimating what I know. Cartter and Scotty would be Socrates, in which case paying close attention could only make me more useful, if not to them, then at least to myself, so I go on building my world around my boys – guarding my time with them, relishing being their Daddy, writing about them as if my life depended on it. Maybe my attachment to them outwardly resembles the weepy indulgence of a silly man or the desperation of an addict. Inwardly, it seems prudent. God knows what I’d do without it.