Some of the best conversations I have with my second grader come in the last few minutes before I drop him off at school. We ride all the way across town together in near silence, just the two of us, and then as we roll onto campus, we’re suddenly ready to talk.

He wakes me up twice each morning, the first time around 6:30 when he sprints out of his room to the kitchen, afraid of the dark hallway in between. The second time is around 7:00. He either flips on the lights or gets his little brother to come back with him to make sure that I get up and get him to school on time. He likes to be early.

Squinting into the bright light of the kitchen, all I want is for him and his brother to be quiet, so I don’t waste time getting out the door and into the van. I use the button next to the steering wheel to open the sliding rear door just enough to allow Cartter to climb in before quickly closing it. I start backing up before he even sits down, eager to make it through the crosstown traffic and drop him off so that I can flip on NPR or Fox Sports radio and listen in peace.

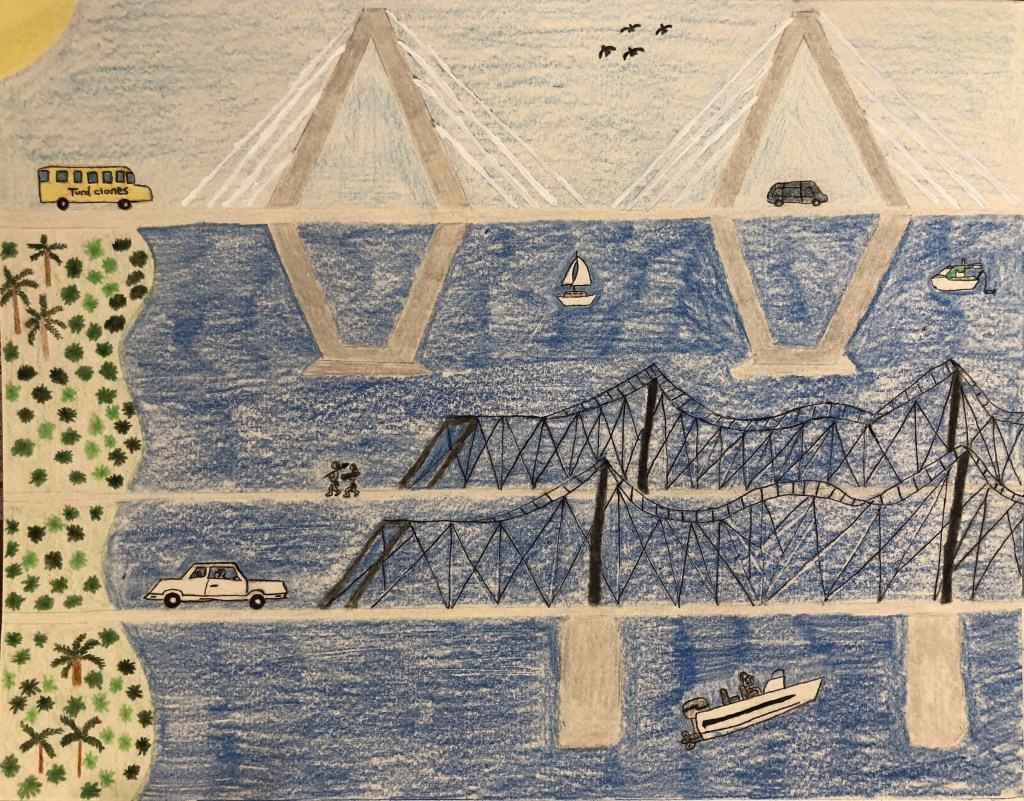

By the time I make it through the stoplights heading south on Hwy 17 and merge onto the Ravenel Bridge that spans the Wando and Cooper rivers, I’ve adjusted to the reality of the situation, that there will be no Star-Trek-style teleportation to Cartter’s school. Sometimes, I’ll make a joke once I get into the appropriate lane. On occasion we’ll see the school bus, and I’ll make a show of angrily passing it. Cartter’s afraid to ride the bus even though some of his friends are on it. It has a little sign on the side that says “Cyclones,” and I call it the turd clone bus as we zoom past it on the way up the steep hill to the top of the bridge.

When I was a teenager, my dad would drive me over the old Cooper River Bridge to 5 a.m. swim practice in his Monte Carlo, no talking, just eerie, dissonant classical music playing on the stereo, no other cars on the road. The bridge into town was two narrow lanes, a behemoth of rusty steel deemed structurally unsound over 30 years prior. I still have nightmares about driving up onto it and finding that it suddenly ends. When I got a little older and got my license, I touched 100 one time coming down the old bridge’s first hill in my Volvo on the way to practice. There was a little pullout at the bottom before the road bent to the left and started back uphill, and I thought I might lose control. I rode the brake on the way down after that.

The new bridge is 8 lanes, a single steep climb followed by a long, gentle descent to where interstate and Mount Pleasant traffic merge onto the crosstown, the worst part of the morning commute. Cars merging across three clogged lanes, brake lights and red lights as far as you can see; the crosstown is the part of the journey I most want to skip, the morning commuter’s equivalent of parenting an infant, frazzled by a need for alertness that supersedes fatigue, jolted by other drivers’ unexpected movements. The first night in the hospital after Cartter was born, I didn’t sleep at all. Every time I got close, I would spring awake at the sound of him moving, terrified that he would suddenly die. For months, hell years, I thought I would never sleep again, constantly waiting for him to start crying in his room down the hall, imagining I heard him when I didn’t. “When will this end?” I wondered. Danyelle and I had many a talk about just making it through.

Past the crosstown, it’s just a small bridge across the Ashley and a single stoplight to campus, and as I turn around the final bend and the drop-off spot comes into sight, I feel Cartter’s butterflies floating back and forth between the middle of my chest and the pit of my stomach. Every time. Suddenly, there are so many interesting things to talk about.

He asks me about cavemen, and he says they couldn’t talk. I make guttural noises and utter single words at a time to imitate how I think early man’s speech might have started out. He wants to know why we know how to talk, and I theorize that after so many thousands of years of our ancestors developing language, we have the words and the mental machinery in place already, so we’re able to acquire language quickly. Cartter is amazed that our ancestors were cavemen, and I realize how right he is to be amazed. “Yeah,” I say, “it’s pretty incredible how many people had to not die for us to be here right now.”

And just like that I’m at the front of the line. Time to push the sliding door button and let Cartter hop out and face the day on his own.