My neighbor has a way of looking at you like he’s surprised by everything you say. His normally elusive eye contact lingers a moment too long, his jaw hangs open, and he gives a half smile that hides anger in amusement. I’m not sure what I’ve done to earn a place that is so decidedly beneath him, yet here I am.

“I go full speed on my kids,” he says standing beside me in the yard, beer in hand, as his daughter calls to him from their stoop to come inside and play Monopoly.

“You go full speed in Monopoly?” I ask.

Surprised face, “Yeah, they need to learn about losing.” Beer sip.

It’s the Friday before Christmas, and people in our little subdivision are out chatting, happy to be off work, rolling past in SUV’s on their way out to dinner. I’m content to talk to my neighbor today even if we don’t see eye to eye on the importance of full-blown competitiveness in a game of Monopoly with our kids. For me, Monopoly is a game made to pass the hours on a rainy day. Its list prices and rules are meant to be flexed, and its value is in the way it occupies the children’s attention and satisfies their imagination. For Surprise Face, strictly adhering to the rules makes the game go more quickly, and competing full-bore teaches his kids about losing. That’s what he tells me anyway.

Apparently, he’s something of a poor sport over at the tennis club, declining to shake hands and claiming injury after losing a match. I assume the irony is lost on him. After all, he thinks he needs to teach his kids about losing. I can picture him tromping through a garden that’s just about to bloom, pulverizing new buds, tennis racket in one hand, beer in the other – These flowers need to learn about losing! It’s a harsh world out there! Standing with him in the dwindling daylight on the Friday before Christmas, though, I’m happy for his company, thankful that he’ll let our boys play together, even if mine haven’t been properly thrashed in Monopoly.

Our kids are taking turns tackling each other in the grass nearby while we talk, a little boy foursome in Target clothes wrapping up around the waist and tumbling to the ground with a combination of grace and abandon that would make any football coach proud. As they fatigue, though, they stand more upright, and what had been proper form tackles devolve into helicopter moves that end with someone being flung to the earth and landing with a thud. Surprise Face reminds his boy that he’s the biggest after the boy endures a particularly rude takedown. I’m happy to let him set the limits, even if they are unfair to his kid. In his way he’s ensured that our little social hour, now nearing its close, will end without incident. Zipping up my jacket as the two of us look away from the boys and prepare to put a bow on our chat, I ask him, “Do you play cards with them?” No. Beer sip. Conversation over.

Back in the house my seven-year-old Cartter sits across the coffee table from me, looking me dead in the face and holding his eyes open wide, straining against the water that’s involuntarily filling them. We’re playing cards, and I’m going as close to full speed as I get with him in any contest.

We’ve been playing cards at that table since Cartter was three, when I hurt my back during the Covid lockdowns and discovered a love of 60’s Blue Note jazz while confined to the house. Cartter was an Uno man then. I listened to Wayne Shorter on the Sonos while he won, lost, tried to cheat, delighted in the power of the special cards, and gloried in my attention and our equal footing in the game. It was a joy to behold. Over the years our card playing time has waxed and waned, but lately, we’ve been playing a lot. Cartter’s new game is Rowboat.

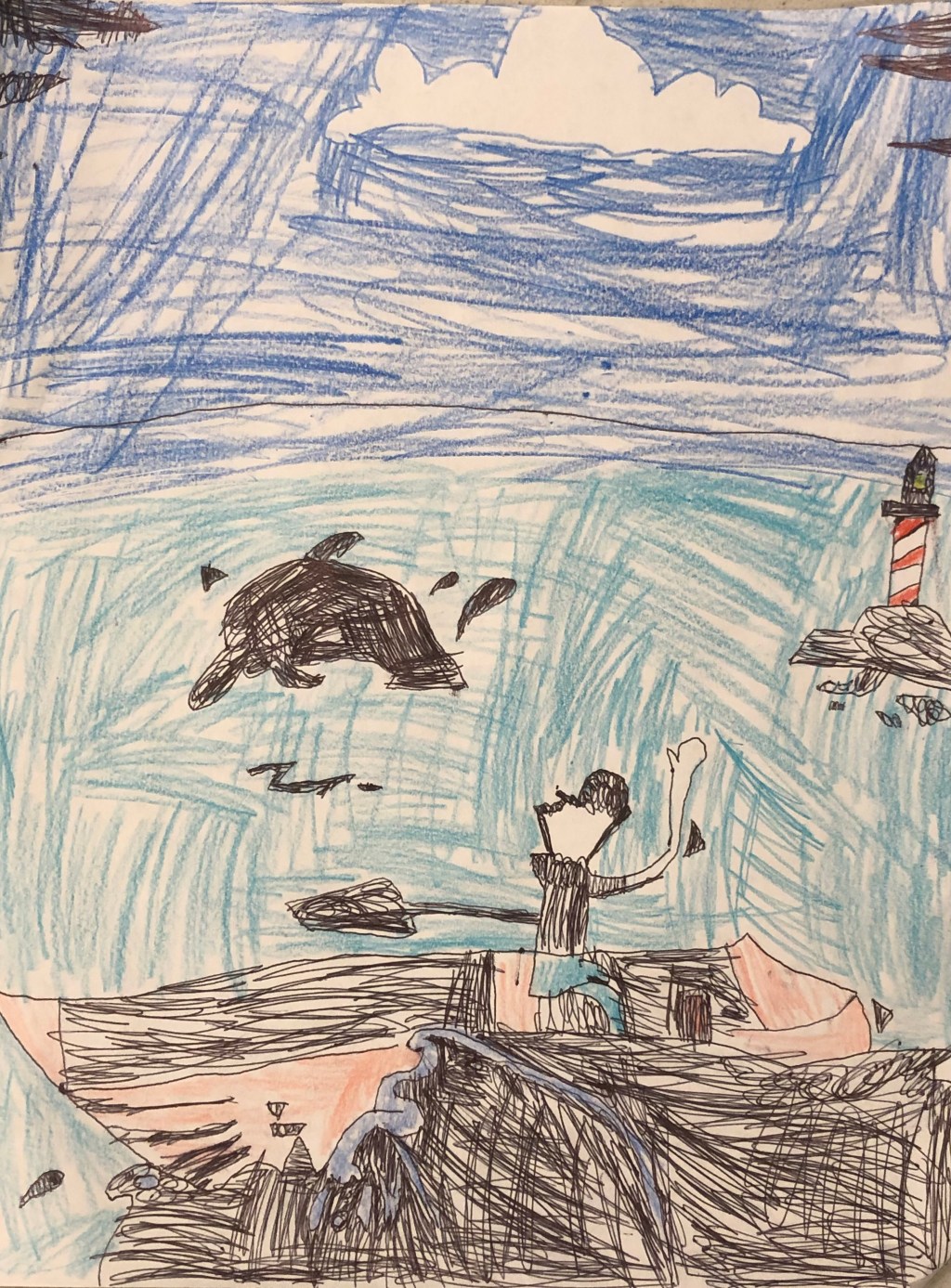

Rowboat is basically spades with the added twist of a nautically themed deck and a “tide” that determines the number of cards for each hand and the trump suit for each turn. It isn’t meant for small children. There’s bidding, and the box says 13 and up. Cartter has been cheating at Uno since he was three, though. He loves Rowboat, and I can go pretty much full speed. Of course, going full speed in Rowboat is different from going full speed in Uno. The water is choppier, and I have to watch where I’m going, like when Cartter is sitting across from me after a foolhardy bid that saw him capsize, visibly summoning all his inner strength to appear unaffected, even as he lamely asks me, “So what does that mean?”

“Well you had 50, and you didn’t make your 8, so what does that give you?” I say.

“Negative 30?”

Nodding, I’m impressed how quickly he does the math. “Mark it down.” He does, and I get to work shuffling the deck.

He’s stopped the tears from falling down his face, but they’re stubbornly lingering in his eyes. He stares, looking at me as if to say, I’m not crying. You can’t see me behind this look. Can you?

“It’s ok,” is all it takes for him to avert his glance, a sneer of disgust flashing across his face, my reassuring comment like a weed choking his budding resilience. “You wanna deal?” I counter, and just like that he’s back, battling, showing discipline, keeping score, enjoying. Then he sinks again and pretends he’s not about to cry.

Finally, on a big tide he makes a bold but serious bid. If he hits it, he’ll be right back in the game. I’m pulling for him, as I watch his beautiful little card savant mind in action. He can’t help but talk his way through his hand – “I gotta warn ya. I got a really good hand.” “I wasn’t counting on that.” “I’m not gonna win those two, because I won’t be able to follow suit.”

“Sounds like you have a good plan,” is all I say.

On the last card, I’ve left myself with a strong play, and I’m worried. If I beat him, he’ll miss his bid and sink again. It will crush him. We wait and look at each other. We play our cards at almost the same instant, Cartter just a hair later, clenching his fist and yelling silently to himself as he realizes he’s beaten me by one, good enough to collect the last book and score 70 points. I’m relieved. Nobody’s reached 200 yet, but we stop there. I managed to go full speed through the chop and not throw my boy overboard.

Losing needs no introduction. It greets us the instant we enter this world, ripped from our mother’s womb, screaming and crying. Throughout life we lose games; we lose control; we lose loved ones. My seven-year-old holding back tears clearly already knows about losing. I don’t need to thrust it upon him as some sort of sadistic way to teach him to grow up. Growing up is something we do ourselves, not something we do for other people. I see my son doing it himself, without needing or wanting my help, like a delicate young blossom waiting on the perfect moment to open up and reveal itself, anticipating the opportunity to flourish, to be noticed, not to be interfered with.

Occasionally, I manage to give him the proper space, to see him at his best, and let him know about it, like when I’m watching him manage his emotions as he deals out the tide, and I tell him, “You’re fun to play with.”

“What?” he says, briefly snapped out of focus.

“I said I like playing Rowboat with you. You’re fun to play with.”

I’ll never be able to take a compliment as well as he can. “Thanks,” is all he says. He says it plainly, sincerely, with real gratitude. Then he carries on dealing, growing up full speed whether I like it or not.

A Rumor of War

One of the perks of being on the other side of the toddler phase is watching the parents of younger children at the playground nervously follow their kids from station to station, coaching as they go (Wait your turn!), and occasionally breaking down and climbing onto the equipment despite the sign’s clear declaration that it is “for children ages 5-12.” Danyelle and I are now the parents sitting in a sunny bench, chatting, unable to prevent our minds’ instinctive judgement from springing to the fore in a single, unspoken word – Idiots.

We used to be like those parents, looking up self-consciously at our pathetic, tottering children, ready to catch them lest they fall off the equipment and break their necks. Now, our kids have enough balance and sense that the likelihood of death by playground has plummeted to an almost infinitesimal possibility, and we’ve had enough experience with booboos that the value of allowing some independence outweighs the risk of the boys potentially incurring a significant injury. Better for them to have their fun and for us to put off worrying until something actually happens. Of course, whether something’s happened can be a matter for debate.

As I walk into the back to help out with the bedtime preparations, I find Danyelle in Scotty’s room, brow furrowed, folding clothes. “I feel bad,” she says. “Scotty has bruises all over his legs.”

Scotty and his brother have spent the better part of the day outside, running around with a little neighborhood boy gang. We haven’t really had to entertain them at all, and Danyelle is feeling guilty. I glance towards the boys’ bathroom, and I see that Scotty is in the tub. “A bath?” I ask. They haven’t taken baths in years. Danyelle just shrugs at me from her spot in the middle of Scotty’s stye of a room.

Making my way to the tub, I discover that Scotty’s legs are spotted with dark shiny patches resembling bruised up apple skin. He’s draining the tub, enjoying the last seconds of revisiting his babydom, pouring water over his body with a cup. “What happened?” I ask.

“I got into a war.” He says it quietly but assuredly, looking down undistracted from the little bathing ritual he’s performing on himself.

“What?”

“We were playing with Jonah, and I got into a battle.” He looks up at me with his round blue eyes, totally unsuspecting that there would be anything wrong with getting into a battle, his hair wetted and swirled into a cool do on the top of his head.

“Did you cry?”

“No.” He’s standing up now, and I’m putting his alligator hoodie towel over his head. “Well that’s good.” Another post-toddler perk: your five-year-old comes home after a hard day’s play and tells you war stories.