Shopping

Crowds, lines, salespeople, spending money; everything about Christmas shopping gives me anxiety. I remember my friend Matt getting me to go to the market with him when we were teens and thinking, “Why do you want to spend our time this way?” Of course, I was glad that I was my friend’s chosen company, and I was glad that if I was going to go Christmas shopping, I didn’t have to go alone.

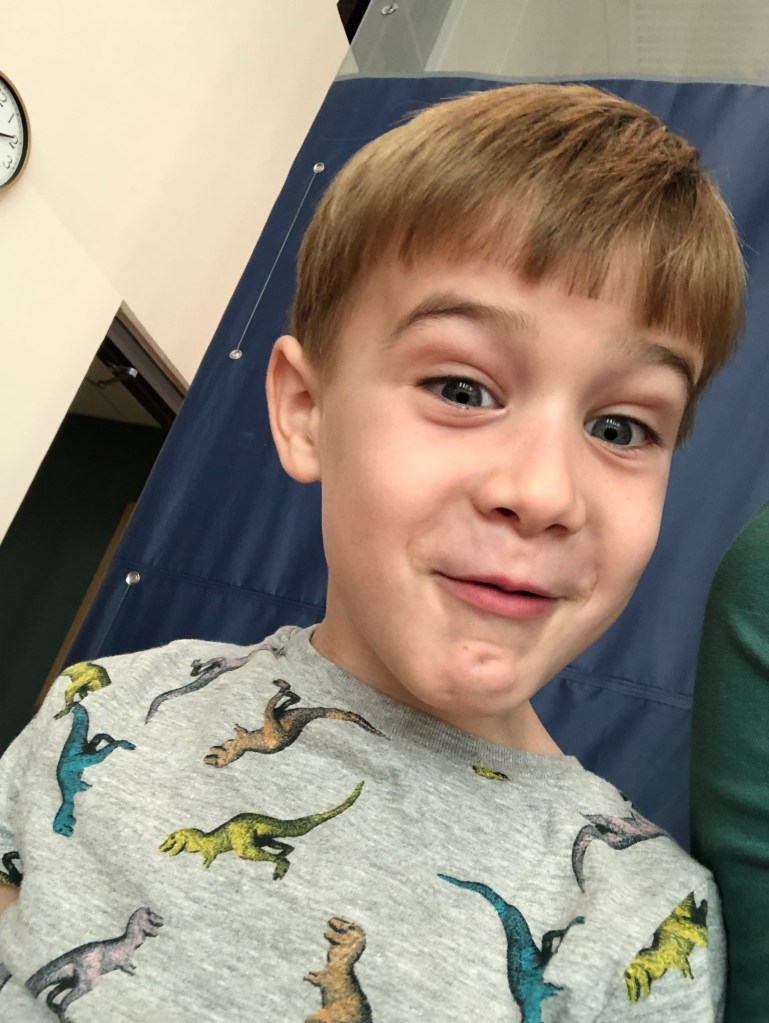

Backing out of a spot in a crowded parking lot at Mount Pleasant Town Center, I want to explain to my seven-year-old how grateful I am that he’s accompanied me on my latest Christmas shopping outing. The spot is tight, and I have to use all my mirrors and the back-up camera. “I have to tell you something,” I say to my boy sitting in his booster seat in the second row of the minivan. “It’s serious. I just need to back out first.”

Cartter had not wanted to come with me that morning. He’d been out walking the dog with his mother when I made chicken salad and packed us a lunch. When I told him we were going Christmas shopping, he whined and tried to get out of it. I quelled his little protest with the explanation that he needed to get something for his little brother, though, and as is usually the case, once I had him in the car with me, he was content. Danyelle says that Cartter complains of boredom when she drives him around. He doesn’t do that with me.

Instead of crying bored, Cartter thinks and asks me questions – “How does the Earth carry everything?” “What would happen if it all got to be too much, and the Earth started cracking up? Would we fall into its molten center? Or would we fall off into space?” He shares facts too – “A man can hold his breath for 30 seconds in space and then after that, you die.” My new Christmas shopping companion – like a humanized Siri, specializing in gravity-induced apocalypse musings and space death factoids.

Together we dropped off cards and oatmeal cookies at my stepmother’s house and at Matt’s parents’. Cartter stared at the paintings in George’s front room and asked why she does so much art, lingering to look at it a moment longer, as I opened the door to leave. At the Grucas’, he bashfully held up under Matt’s dad’s teasing, declining an invitation to their summer house and fumbling with a folded up map he’d drawn, unsure how to respond to Gary’s suggestion that we get a pony for his brother. At our picnic at waterfront park, I watched him look out at the harbor and eat his sandwich.

“What?” he asked when he caught me staring at him.

The answer escaped me like the last bit of helium sucked from a balloon. It bounced out as matter-of-factly as if I’d been saying, “I don’t know,” only it wasn’t “I don’t know.” It was, “I love you,” and it prompted almost identical stifled laughter from each of us as it hung there in the air between us. I’m so glad he didn’t think he had to say it back, that he just took it, and that we could both laugh. I never knew how silly “I love you” could be.

In the parking lot at Town Center, Cartter is ready for my serious divulgence. “OK, you can tell me know,” he says once I shift the van into drive. People are walking in front of me, and I have to turn onto the little lane that leads toward the exit while watching for other cars backing out. My focus is split between trying to explain to my son how much I’ve always loathed Christmas shopping and making sure I don’t get in a car wreck due to Christmas shopping. I find myself looping back over things I’ve already said, kind of spiraling my way to a point, not satisfied that I’m being clear. I’m telling him about being nervous around crowds and guilty about spending, and when we finally get to the stoplight and are waiting to turn left out of Town Center, I turn around and see him looking out the window. I can tell he’s thinking about something. I think I might have lost him, and I’m kicking myself for being so wordy. I know that if I could just say it the right way, he’d be able to relate. I’ve just finished witnessing his own struggle with Christmas shopping.

Like me, Cartter’s not a big fan of crowds. After we finished our picnic, I drove him to the market, where I went shopping with Matt all those years ago, and as I made an 8-block circle searching for a parking spot, Cartter told me he didn’t like this place.

“Why? Too many people?” I asked him.

“Yeah.” He wanted to go to Wonder Works, or “the kid store” as he calls it, and when I finally pulled into a space past the market’s north end, a light rain threatening to grow heavier, I sat there for a minute debating whether to get out and walk or acquiesce to Cartter’s wishes. Then, Cartter remembered that Wonder Works has a stall in the market, and I let him lead me to it.

“It’s all the way down there,” he said after we crossed the street and walked in among the booths underneath the roof. It was Sunday, and the crowd was not as thick as it often is. We passed by booths with sweetgrass baskets, paintings by local artists, and all sorts of trinkets. My favorite was the frog-shaped guiro that sounds exactly like a frog when you run a stick along its ridged back. “Oh yeah! I have one of those!” Cartter told me. “Mommy got it for me.”

We paused very briefly a couple times. Cartter was interested in a trio of carolers at one of the crossing streets between buildings, and he thought for a moment that a stuffed panda might be a good gift for his brother, but we mostly just slowly made our way down the narrow path between the booths with our destination in mind. I noticed Cartter’s shoulders involuntarily rising up towards his ears and his head jutting out slightly, like a turtle trying to retreat into its shell, and when he peered slightly over his shoulder, I let him know, “I’m right behind you, buddy.” At the tiny Wonder Works stall, Cartter landed on a stuffed Pokémon (Charmander) for his brother, and he held it on our walk back through the market, his eyes going from left to right as if perpetually about to cross traffic while I guided him with a gentle hand on his back.

Sitting at the stoplight, waiting to leave Town Center, I know Cartter understands that the stimulus of Christmas shopping is overwhelming. I also know that I’ve made it more fun than he thought it would be. That stuffed Charmander he got to pick out for his brother really went a long way, so much so that when we were about to drive past the house, and I asked Cartter if we should keep going to hit some stores at Town Center, he said, “Your choice.” I want to return that generosity to Cartter now, so before the light turns green and I have to turn into traffic, before I’m fully satisfied that I’ve made my point about how negatively I generally feel about Christmas shopping, before Cartter turns away from the window to meet my gaze, I tell him, “I really like Christmas shopping with you, though,” and I get to watch as a smile flits across his face for an instant.

When we get home, Danyelle is on a ladder stringing icicle lights across the front of the house. I’ve never been one for decorating, but I love that we do the icicles, that it’s our thing. They look perfect on our wide, ranch house, and nobody else in the neighborhood does them like we do. We have gutters now, and it’s much easier to hang the lights. Two of the strands have a different kind of connection, and we have to take them down and restring them, but it’s still easier than it’s ever been, kind of like Christmas shopping this year.

It’s strange – the tree has been in the house for over a week now, and I hardly notice it. Instead of being sucked into its lights each night in the living room, feeling anxious about the approaching festivities, we forget to even plug it in most nights. Instead of a massive pressure-packed chore, Christmas is starting to feel a little bit more routine. We know what’s coming – a trip to Virginia to see my mom and her family, Matt back in town for a while, a family gathering or two, a friends party – and it all seems somehow more manageable.

Somehow, I feel myself gliding into the season like never before. When I was leaving the Grucas’, I was surprised how easily a return “Merry Christmas” pushed past my lips, and after dinner, I find myself joining in arts and crafts, making a Christmas ornament out of a plastic cup at the kitchen table with the kids. Is this the difference between having a 4 and a 6-year-old and having a 5 and a 7-year-old when Santa is on the way?

A few more years of believing in Santa. If that. In a way we’re almost to the finish line. Danyelle has started doing Elf on a Shelf. She basically does an art project every night before bed so that the kids will wake up and find the toy elf having gotten into some sort of mischief when they wake up. In the past I think I would have been annoyed. This year, I mostly don’t care and am mildly amused by how much the kids like it. Yes, something has definitely changed. I know for sure that something’s happened to me. I must be losing my mind, because I actually can’t wait to take Scotty Christmas shopping next weekend.

Christmas Program

As Danyelle and I flee the Christmas program after party, the friendly teacher we just met is all that stands between us and freedom. She’s in the hallway basking in the relief of the show’s conclusion, swaying in her flowy dress so that her long, curly dark hair slowly swishes from side to side. Danyelle and I just escaped a kindergarten classroom full of kids and parents, chatter bouncing loudly off the walls, tiny tables and chairs set up throughout like an obstacle course, a tray of little banana bread squares and dixie cups of orange juice stuffed in a corner. It was a shitshow, and we fixed Scotty a plate and were the first to leave. We really want to flee the premises before all the other parents in all the kindergarten classrooms come streaming out, but I can’t help but want to stop and speak to this woman.

We met her an hour earlier that morning when we’d been the last parents to arrive, just in time to watch everyone pour out of the building because the fire alarm went off. After driving the van up onto the sidewalk and down a grassy hill to maneuver into the last available parking area, we walked over to where Scotty’s class was standing. Somehow, it was weird that Danyelle and I had gone over to where our child was waiting post-evacuation. We were the only parents standing next to the three lines of kindergarteners being monitored by a group of teachers, and this lady with a funny accent was the only one who didn’t avoid eye contact.

There was no fire. The fire department showed up, though, and administrators buzzed around with plastic smiles glued on their faces, apparently driven to the brink by the untimely disruption and in desperate need of someone to tell them, “Relax. It’s fucking kindergarten.” Funny accent lady joked that the kids would probably sit still more easily after all the excitement.

I’m looking forward to reconnecting in the hallway now that the play is over, and I offer that “Feliz Navidad” was the best number the kids did. When I detect a hint of confusion, I follow up with, “You’re the Spanish teacher, right?” Nope, that accent is French. She laughs at me. “Oh, that’s what I meant,” I say. “The French song was the best.” She doesn’t care. She worked with the kids on all the songs. She doesn’t know which kid is ours either, a generous confession of ignorance that levels the playing field after my gaffe.

I tell her Scotty is ours, that he has been so excited for the show, and that we so enjoyed seeing his enthusiasm – his approach was very different from watching our shy first-born two years ago. “Oh yes,” she says. “Those second-born children. It’s different. I know all about that.”

I wonder how she knows all about it. Does she have kids? Is she a gregarious second-born child herself? Or does she just mean she’s witnessed the differences between older and younger siblings as a teacher? No time to ask. Parents are starting to finish making their kids’ muffin plates and trickle out into the hall. Time to get to the car and drive it back over the sidewalk before the throng of program-goers blocks our exit route. We don’t want to be here any longer than we have to, so her blanket statement about birth order will have to remain unexplained. One thing’s sure – it definitely applies to our kids. The kindergarten Christmas program was clear evidence of that.

During the show Scotty belted out the songs and fully committed to the choreography. He was like any other worry-free kid up there, enjoying himself. I realized about halfway through, when they sang “Go Tell it on the Mountain,” that he’d been singing the tunes to himself around the house for weeks. When Cartter was part of the same production, he lip-synched and performed the choreography like he was afraid of being struck by lightning. In “Santa Claus is Coming to Town,” other kids reached their hands to the sky and shouted. Cartter ducked his head and barely raised his hands above his shoulders. I remember being surprised how little he looked. Scotty, on the other hand, towered over the other kids on his row when they stood to deliver their line – “We try hard to be good and never shed a tear.” In contrast to Cartter’s timid delivery, Scotty went with a power move and stuck his hand in his pants for his big moment.

Scotty was so invested in the play that when I floated the idea of him missing school, he panicked and said, “But my Christmas program is on Monday!” I was able to parlay his concern into increased hydration and napping, and the cough that would normally have lingered for two weeks cleared up over the weekend. Cartter would never miss an opportunity to skip school, Christmas program be damned.

Danyelle’s and my excitement about school productions has moved inversely to the kids’. Not that we were in the front row during Cartter’s kindergarten show, but we weren’t the last ones there and the first ones gone either. Cartter was dressed up in a festive button down and little kid chinos for his play. Scotty wore a solid red T-shirt that Danyelle turned around backwards after he dripped toothpaste all over the front. I’m not saying we don’t care. At the start of the show when they filed all the kids in and sat them in the bleachers on stage, I was mildly disgusted by the pathetic display all the parents made of calling to their kids, waving with one hand, recording with their phones in the other, but I couldn’t help craning my neck and waving when Scotty scanned our section, and I couldn’t help feeling disappointed when he didn’t see me. I care, but I have some perspective at this point. I realize it’s fucking kindergarten.

Walking away from the kooky French teacher, about to go off roading in the minivan, I’m proud of my little wee wee toucher, proud that he’s so unburdened by self-consciousness, that he’s so capable of being part of a group and performing his role with full-throated confidence. I wish it were so easy for Cartter. I wish it were so easy for me. We first-borns have a tendency to worry. We focus too much on risks – if I raise my arms in the air like everyone else, I’ll look pathetic and needy; if the world gets too heavy for itself, it will break apart, and I’ll fall into space and die of asphyxiation. It can make life a much scarier ordeal. I’m glad Scotty is less troubled by such things.

Instead, he’s more focused on simpler, but no less important matters. Just last night he stood in front of the shower, dripping wet with his alligator hoodie towel hanging from his head and draped over his shoulders and asked me, “What’s in my balls?”

I told him not much, but one day they’d drop down, and he’d have big ol’ balls. This was interesting enough judging by his eyes doubling in circumference, but it didn’t satisfy his need for an answer to what’s in there. Ultimately, we landed on blood and squiggly stuff, but Scotty still wanted to know more – “What do we have them for?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“So they’re just for decoration?” he asked.

I had to laugh, and I also had to agree. For one thing, I loved his logic. If his daddy doesn’t know what something is for, it must be purely ornamental. For another, Scotty’s balls pretty much are just for decoration, because, you know, he’s in fucking kindergarten.

Brotherhood

I finally have a working theory for why the annoying kid across the street is so stuck on our boys. “He’s obsessed with them,” their mom says. Yeah, that may be true lady, but you’re making this awkward. We really don’t want to have a conversation with you about your kid ringing our doorbell at 8 a.m. on a Saturday and every single afternoon as soon as the van pulls up in the driveway. What is an obsession to you is an annoyance to us.

Before, I thought the explanation for this desperate behavior was that the kid was just plain bored and that his parents didn’t want to deal with him, but there are other kids he could go bother, and it’s not like he gets the warmest welcome from us when we come to the door after he presses the ringer thirty times in rapid succession. In choosing to seek out our kids first every day, he’s willingly subjecting himself to the unpleasantness of Danyelle’s and my scorn. Other kids’ houses are just as close by, so his choice isn’t just about proximity. Maybe those kids are less available. Maybe their parents are even meaner and more annoyed than we are. Those are both possible explanations, but I don’t think either of them are quite it – Danyelle and I have been working hard to make our kids less available, and we can get pretty mean and annoyed. I can’t know for sure, but I’m beginning to suspect that his mother isn’t lying, that he is, in fact, obsessed with Cartter and Scotty, and I think that it’s because he really wants what they have – a brother to play with.

The resulting obsession causes him to act in all sorts of ways that Danyelle and I find unacceptable, and we’ve come up with various means of dealing with it. At first, we were motivated by the apparent need to protect the brotherhood, which neighbor boy seemed intent on driving a wedge into. These days, we’re more concerned with limiting this kid’s influence (he’s kind of a spoiled brat). The brotherhood is far too strong to be fucked with by this little pipsqueak.

Scotty laid it out perfectly in a conversation with a little girl prancing around in her dress on the neighborhood playground the other day. “You aren’t friends,” the girl said to Scotty, the two of them facing each other on the little bouncy bridge, a certain nanny-nanny-boo-boo, you-can’t-catch-me quality to her voice.

“No,” said Scotty matter-of-factly. “We’re the opposite of friends. We’re brothers.”

During the same conversation, Scotty also claimed that “face is the opposite of head,” making him perhaps the first person in human history to identify that friends and faces are the opposites of brothers and heads. There are undoubtedly some interesting linguistic and philosophical ideas to unpack there (I mean, think about it – isn’t head kind of the opposite of face?), but suffice it so say that I think Scotty is onto something. After all, who am I to disagree? His understanding of the word “opposite” might not be perfect, but his understanding of the concept of “brothers” is surely far greater than my own.

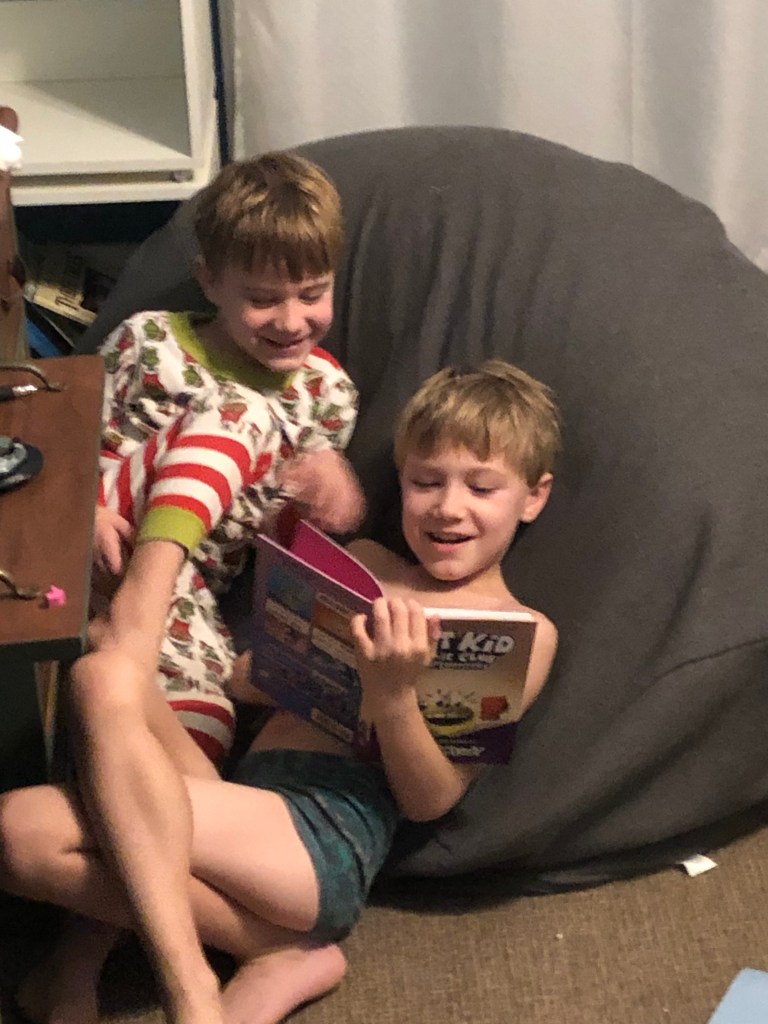

By Scotty’s definition my friend Matt was the furthest thing from a brother. Then again, if friends and brothers really are opposites, Matt’s probably my best shot at understanding what being brothers is actually like. We were still prepubescent children when we met in middle school, and like Cartter and Scotty, we pretty much spent as much time together as possible. Matt was the only friend I was really comfortable around, and the only times social situations were really enjoyable was when Matt was there. Without Matt, I was like Cartter flying solo at a birthday party with no siblings, standing around twiddling my thumbs trying not to look too nervous. Like Cartter and Scotty, the two of us were constantly engaged with one another, our conversations not so much single interactions but rather one long, laughing discussion broken up by the times we were apart, but this was young male friendship, and it was like brotherhood in the sense that black is like white because both are colors. The two of us could talk endlessly, but there were certain boundaries that we both respected, boundaries that, judging from my observations of Cartter and Scotty, do not apply to brothers, boundaries like not being incredible dicks to each other and keeping our hands to ourselves.

“Do they fight?” a neighbor friend asked me the day after Scotty unleashed his theory of opposites on that sassy little girl. I was picking the boys up from his house. Solo play dates are not a thing for my kids. If one goes, so does the other, a packaged deal as they say. Things are different for this dad, who has a boy bookended by a younger and an older daughter, and we were discussing the phenomenon that is the incredible closeness of the brothers, separated by just 20 months in age. I told him that Scotty had already chipped one of Cartter’s permanent teeth in half. He seemed sufficiently impressed, but having grown up with brothers of his own, he added with a knowing look, “Just wait.”

My sister and I fought as kids, but if it had been anything approaching the physical brutality our boys exhibit, the punishment would have been extreme. Pushing Betsey around just wasn’t an option. With Cartter and Scotty, though, it doesn’t seem to matter much what punishment we throw at them or how scary mad I get. They must wrestle and beat each other up.

Supposedly, this brother fighting is a pretty universal phenomenon, particularly when the combatants are close in age. In high school Matt and I had a friend who had a brother one grade above us. They lived nearby to Matt, so he visited their house regularly. He would tell me about them getting in bloody fights with each other, his eyes wide, emphasizing the shocking nature of these battles – “You wouldn’t believe it,” he said. I don’t think those two are particularly close these days. Rivalry won out in that brotherhood.

I like to think that for Cartter and Scotty, the fighting will ebb and they’ll enjoy a close relationship throughout their adulthood. “Do you think they’ll go off to college together?” the neighbor friend asked. I said I thought there was a good chance and told him the story of a pair of brothers I knew when I was coaching the year-round swim team. I was coaching the younger kids and watched the two of them from afar as they swam through high school. Both were very talented. The older set the state record in the 200 butterfly and got a scholarship to swim at Pitt. He was a big-time talent, one of the better swimmers I’d been around, and I’d been around some elite kids. His younger brother, though, was one of the greatest swimmers in South Carolina history. Coming out of high school, one year after his brother, he was easily one of the top five recruits in the country, a state record holder in multiple events. Everybody wanted him. They offered him a scholarship at Stanford, home to arguably the greatest swimming program ever. Contrary to the wishes of some who hoped to see his stardom rise, Zach went to Pitt, because he wanted to be with his brother.

I was one of the people who hoped he would go to Stanford. Now, I think I’d hope for Scotty to want to follow Cartter. It would mean that their bond had lasted through the teen years, through all the friendships, girlfriends, and fighting. It would mean that the real-life fantasy that the neighbor kid wants so badly and that I can see but not fully comprehend had survived. It would mean that they were still brothers in every sense of the word.

For now, the matter is not in question. After bringing the boys back home from the friend’s house and putting them to bed, I drove Cartter to school the next day. He was asking me about what he had to do to become a rocket scientist and was surprised to learn that being a rocket scientist meant getting a job. Apparently, he envisioned working with microscopes and scientific potions in his room. He told me it was no big deal, though. He and Scotty were going to live together when they grew up. I was familiar with the notion. They’ve been telling me for a while that they’re going to have their own house and have babies, but Cartter added a new layer to the story this time – “And we’re gonna get the same job and work at the same place.” He was almost daring me to contradict him, to tell him it wasn’t allowed or that it was impossible so that he could fight me. In that moment he was just like Scotty on the playground talking to that sassy little girl – That’s right. We’re the opposite of friends. We’re brothers. Nothing you can say can split us up. Of course, I was happy not to disagree. Of all the things about my boys that make me proud, none of them is greater than their brotherhood. I don’t fully understand it, its physicality, the coexistence of fierce competition and devotion; their relationship is like its own tiny universe, and I exist on its fringes, an observer. Watching its stars in constant motion, at once harmonious and volatile, is something like watching the latter part of a movie that you don’t want to end. It makes me laugh; it makes me cry; and it makes the kid across the street possessed by the need to endlessly ring our doorbell.

MEMORIES

Sitting in a chair in the guest room, I glimpse a storage bin full of photo albums lying next to a checkered red bag of wrapping paper. The sight of it under the bed sets off a flood of Christmas emotion that spills over the dam of my outward adulthood. Memories of Mom’s boxes of old papers and home movies, her drawers full of photos and Poppin’s basement full of video cassettes and picture framing equipment all flash across my mind. I look up misty-eyed at Danyelle sitting in the bed with the dog curled up next to her before returning my gaze to the thick album pages visible in the corner of the bin, their contents no doubt remnants from the time when everything was perfect, including Mom’s drive to record it all.

The bike I got for Christmas when I was six, the basketball goal that went in the driveway at seven, the trampoline that went in the back yard at eight; all of them come rushing past. Then come all the non-Christmas memories – trips to Sapphire, swim meets, summer vacations; the roaring Christmas floodwaters whisk them all from their resting places and mix them all together. Once upon a time, they were crammed into boxes in the storage space at the top of the stairs and floating in drawers throughout the Sullivan’s Island house; assurances of permanence, collected and cared for by Mom, treasures guaranteed to last a lifetime. And then everything blew up, and the pieces went flying everywhere.

Some of it went to Mom’s house in Mount Pleasant and then to Virginia. Some of it found its way to my house or my sister’s when we were too young and transient to be responsible for it. Some of it ended up in the trash. Seeing a little piece of the remains under the bed in our default storage room where we hide the Christmas presents from the kids, I realize I’m still within the blast radius. I tell Danyelle that “Christmas is hitting,” and I leave the room without opening the bin, without even touching it, telling myself that I’m glad the promises of my youth were broken, because now I’m better prepared to appreciate the impermanence of life and its happiness. Right.

Two days later, I pull the bin out from under the bed and remove the lid, ready to sort through the memories Danyelle and I packed away to make room for our new lives. The top layer is albums compiled by Mom, pictures of the boys over the last few years, pictures of the little faces I see every day flashing across the digital frame in the kitchen, smiling from their spots atop the mantle, running around the house changing in front of me all the time. These albums represent Mom’s inability to stop herself from believing she is the only competent person in the world. If she didn’t catalog our lives for us, nobody would, not correctly at least. Emails would go unsaved, old papers unfiled, special occasions unrecorded, and photos unprinted. Without Mom’s diligence and determination, memories wouldn’t be properly cherished, and life wouldn’t be properly lived. These days, there’s not much value for me in Mom’s ability to be right about everything all the time, but as her favorite villain in Star Trek the Next Generation used to say, “Resistance is futile.” Just take the albums, and stuff them in a box under the guest bed.

Setting aside the Shutterfly albums of pictures from a week ago that only Mom could have thought to print, much less adequately curate, I dig deeper. A framed 8×6 takes me back 30 years to when Charleston beaches didn’t get crowded, and my sister and I could put our arms around each other. A collage of pictures from Sapphire shows Matt and I as awkward 13-year-olds swallowed up by goofy t-shirts, giggling with each other at the beginning of our friendship. A thick, blue album rockets me back and forth decades at a time between my toddler years in Chattanooga, frolicking on the beach at Sullivan’s Island, and moving all around the east coast with Danyelle.

Nearing the bottom of the bin, I’ve given up on any thought of being productive before my noon appointment, my mind instead contentedly absorbed in the task of unpacking this treasure chest, each new discovery like opening a secret door and blowing the cobwebs off part of my soul. That’s when I see a red binder that states plainly in neon yellow block letters stuck to its cover “MEMORIES.” It’s unimportant vibes are so strong that I almost dismiss it and consider this impromptu unpacking complete. I open it anyway with the intent of thumbing through its pages and quickly scanning the photos. There aren’t any photos, though, just page after page of printer paper crammed with single-spaced lines of 12-point font, starting with,

“Date: Sept 15, 1995 8:31 AM EDT

From: LisaLupton

Subj: Re: hurtlin’ thru space”

It’s Mom, documenting our lives in two years’ worth of emails from the time I was 11 until just before my 13th birthday. On page one she tells the story of me reaching 5 feet tall. On page two, Mom details how she and Dad calling me weiner boy led to me discovering my first pubic hairs. On page eight, I’m asking what to do if I like a girl, and eight-year-old Betsey is confessing to forging Mom’s signature on her spelling test. It’s the apex of my childhood, printed, hole-punched, and secured in a three-ring binder. Swim meets, school trials, a Christmas visit to Chattanooga, the buildup to the Masters; it’s all in there, our happy story wrapped up in Mom’s bitingly humorous prose. Dad bears the brunt of most of her jokes. His preoccupation with moving his bowels and his hypochondria are favorite subjects. Mom’s distaste for his mother comes through loud and clear too. A lot of space is dedicated to Betsey’s and my achievements and the funny things that we said. As I get further and further, there’s more and more about swimming and swim team, and towards the end, Mom tells the story of my first morning practice and mentions TJ’s name for the first time – the beginning of the end.

Mom presents herself matter-of-factly. She’s almost flippantly fatalistic about her understanding of the world happening around her, punctuating her thoughts with phrases like “DOOM,” and “The horror,” and “Who can believe it?” before she merrily signs off with a “TTFN.” I hear her voice as clearly as if she were speaking. I see her face wearing a knowing yet incredulous smile. She’s so unmistakably Mom, wittily bulldozing ahead in the name of everyone’s good time, knowing better than anyone how people ought to be enjoying their lives.

The tone is unsurprising. I’ve heard it all my life. The boy in the stories believed all that confidence that Mom projected, depended on it, was comforted by it. The teenager he’d become resented it, but reading Mom’s catalog of our lives as an adult, it isn’t hard to see through all that harsh bravado to the fear beneath.

She’s worried that Dad’s neurosis is going to spoil our trip to see her family. She’s frazzled by Betsey’s impetuousness and resorts to threats when Betsey keeps bringing home failing grades in social studies. She’s frustrated by my habit of throwing up at swim meets. Her world is moving fast, and despite all of her pretending, she doesn’t know what to do.

Her response to my question about liking a girl is “Go to your room, bolt the door, and read Jack London novels to block her out of your mind.” Her thoughts on my sister’s forgery are “Wonder what she’ll be doing at 16.” All that self-assuredness, all that sharp-tongued superiority; reading it on the page it’s so clearly the ironic coping mechanism of a scared young mother who isn’t ready for her kids to grow up.

By the time I read through the last email, I’ve been in the guest room for two hours, and it’s past time to get on with the day. I walk out and leave the treasure chest open and its contents strewn about the bed. It will take two days before I put the bin back together and cram it back whence it came, crawling on hands and knees and fighting it past obstacles that it seems to almost willfully run into, as if it didn’t want to go back into its hiding spot. I crawl from one side of the bed to the other and shimmy it back into place, though – one emotional Christmas threshold successfully crossed.

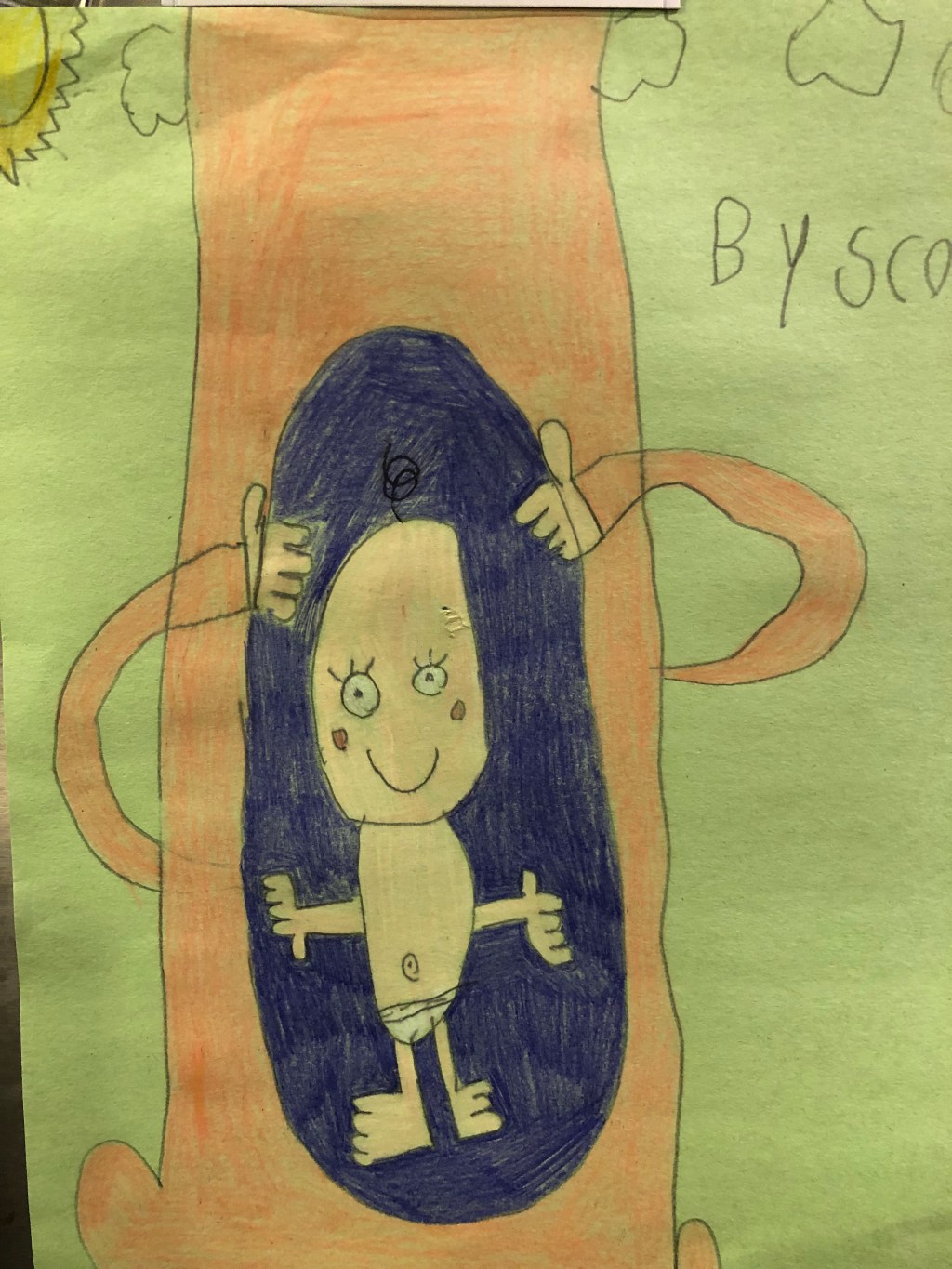

The flood gates are closed again, the million little mental doors shut, memories all resorted and stuffed back in their container store tomb under the bed . . . almost all of them. A precious few are staying out here in the open so that the little rooms whose doors they open can be tended to more regularly. There’s a big wall in the den where I work that I’ve been wanting to redecorate. It’s covered with Clemson sports memorabilia – Sports Illustrated covers and newspaper pages. I’ve been waiting to figure out what to put there before taking it down. Now I know. I’m going to hang Cartter’s Wiki Tiki, the self-portrait monster painting he made in first grade that I use as the banner on my blog site and the avatar on my social media accounts. The Mom DNA that’s flowing through my veins compelled me to get it framed. Beneath it, I’ll hang these treasures that Mom left me – a picture of Betsey and me on the beach, a Sapphire collage with Matt and me in the middle. The red binder full of emails is going up to Virginia with Danyelle and the boys and me. Betsey and her son Maddux are supposed to ride with us. And of course Sammy is making the trip too. A vanload of Mom’s treasure, hurtlin’ through space on a Christmas road trip.