Thanksgiving Play

Walking up the path toward the auditorium, a light mist of rain is falling, and I’m worried that Danyelle is going to make us go inside. It’s 7:30 in the morning. “I don’t wanna socialize,” I tell her. “It’s too early.”

We’d arrived before the teachers opened the gates so that Cartter wouldn’t descend into a panic about being “late.” We also have Scotty with us, because it’s too early to drop him at kindergarten, and we didn’t want to take two cars. I slip around back while Danyelle takes him to the bathroom, hoping that there will be a dry bench somewhere hidden from sight. There isn’t. An egret glides over the marsh beyond the playground, and cars silently zoom across the James Island Connector, the same bridge I watched get built during my first year at this school, 31 years ago.

Behind me the foot traffic heading to the auditorium is picking up. So is the rain. It would be weird to stand here and force myself to reminisce, so I reluctantly go inside. The lobby is unchanged from my school days. I remember the smell of the potpourri fundraiser when I was a third grader. Then, the walls were lined with tables displaying arts and crafts for sale. I bought a gift for my mom that day, trying to be invisible while I did it. Now, the walls are adorned with paintings of trees done by the second-grade class. I’m glad when Cartter’s friend’s parents don’t notice me, as I scan for Cartter’s art.

My eyes land on Cartter’s piece almost immediately. I hope that I’ve intuited correctly and feel validated when I see my son’s name in the bottom right-hand corner. Cartter’s tree is gentle with arched boughs, a happy green foreground, and a darkly beautiful blue and purple background with ominous swirls that denote a sort of fullness. I’m embarrassed, but I stand close and snap a picture with my phone. A nearby mom catches my eye and gives me a little knowing smile.

I want to stand there and look at all the kids’ trees, to see how they’re different, to think about what they might indicate about the artists’ little psyches. I’m drawn to one in particular that has a wide rectangular trunk and angular branches. It’s like a cubist tree. I think it’s fucking great, and I want to stare at it and the others longer, but more parents are coming in, and nobody else is pretending to be in an art museum. I look down at my phone. A text from Danyelle says she and Scotty went ahead and got seats.

Like the lobby, the auditorium is completely unchanged. Danyelle’s picked a spot for us in the middle section on the aisle. I stand there as some dad asks her if she has an extra car seat, a strange request I think. He’s an older guy, too old to have a second grader, and he introduces himself to me by telling me who his kid is. I don’t know his kid. Somehow, he ends up talking to me about his shyness as a child and the speech class he took in college. I’m really glad when he finally excuses himself, and I can sit down next to Danyelle.

“Did you see Knox made the tree?” Danyelle asks me. I have no idea what she’s talking about, and she explains that the little balls on the end of each tree branch have written in them things the kids are thankful for. I consult the picture on my phone, zooming in to see what Cartter included – Mom, Dad, God, earth, pets, Knox, Scoohl, Friends, brother, Brain, heart, Life, Animals, me, and Space. Danyelle and I think it’s funny that our kid is thankful for space.

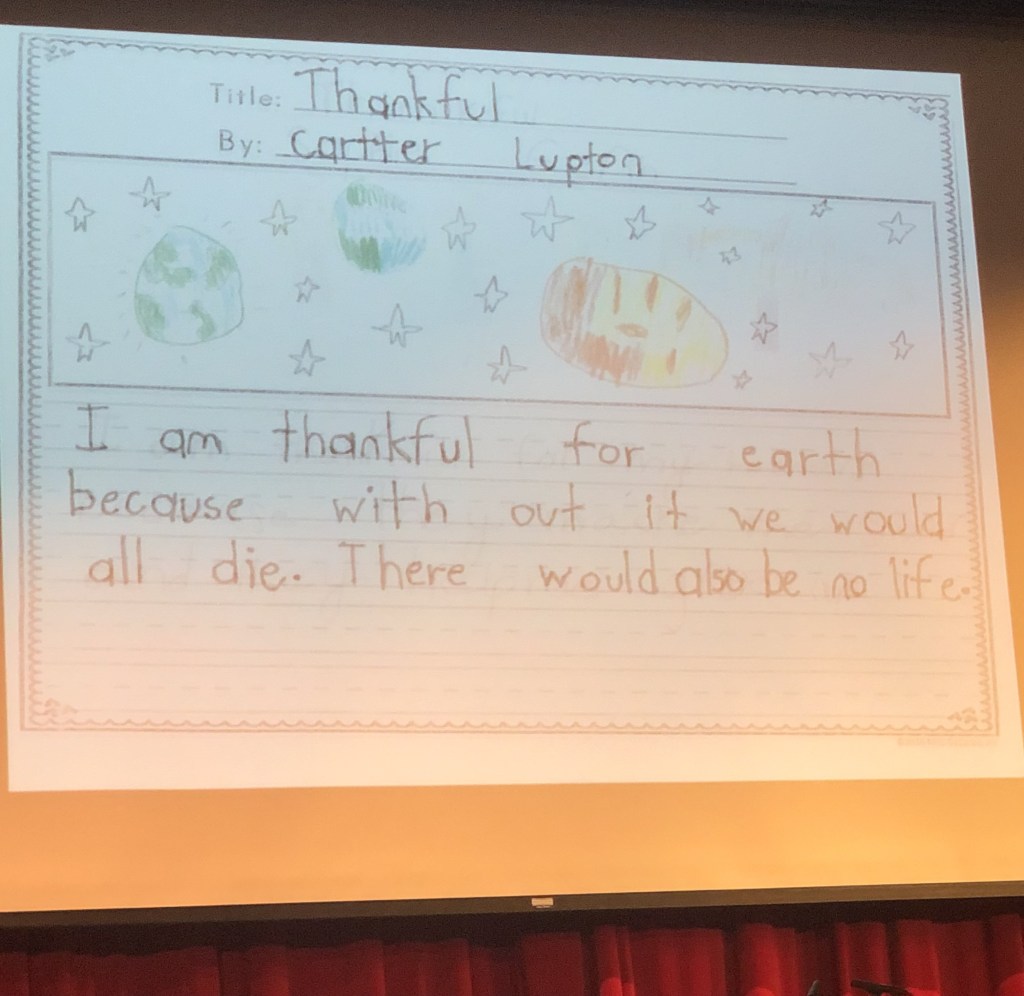

Vince Guaraldi Peanuts music starts playing through the speakers as a projector screen drops down from the ceiling. It’s the preshow show, slides of cards that the kids have made. Last year for the Christmas play it was “my favorite holiday tradition,” and Cartter’s card about us dressing up in matching pajamas got a big laugh. This year it’s “what I’m thankful for.” I open the camera app on my phone and set it in my lap, and watch the slides flip by. Some of these cards are fairly elaborate. The handwriting is a lot neater than last year. I start to wonder if Cartter’s teacher tells all the parents that their kid is the best reading student she has.

The slides are moving quickly. Most of the kids are thankful for their families and their dogs. I fix my gaze to where the kids’ names appear, and when I see Cartter’s, I snatch my phone and aim it at the screen, but my camera doesn’t focus right away. I’m mildly panicked, staring at a beige blur as the entire audience erupts with laughter. My screen comes into focus at the last possible instant, and I snap a picture before the little window into Cartter’s soul is gone forever. “Oh my God,” Danyelle laughs. I look down at the picture in my hands. There are stars and a little globe. It’s Earth, and the sun. It’s a little solar system. Beneath it is written, “I am thankful for earth because with out it we would all die. There would also be no life.” Danyelle and I are happy for our son’s appreciation of not being dead.

After the obligatory speech from the principal and an awkward prayer from the chaplain, the curtain rises, and the show gets underway. Cartter’s scene is second out of eight, so we don’t have to wait long to find out that the costume he was so excited to wear is just a broccoli hat to go with the solid green clothes he was already wearing when we brought him. The kids take turns approaching the microphone to deliver their lines. Cartter’s is “Yes, but mostly vegetarians.” He gets a decent laugh from the crowd.

Each scene ends with a musical number, and Cartter’s is “Mashed Potatoes.” Some of the kids are up in front, and others are in the bleachers in the background. All of them are jumping and twisting, as they shout lyrics about how delicious mashed potatoes are. Cartter is one of the kids in front. His delivery is muted in every sense. He bends and sways like a windblown sapling, makes feeble hand gestures, and silently mouths the words to the tune. My kid is totally in character. He is so broccoli.

The only reason we endure any more of the show is because Cartter will be expecting to see us at the end. The kids yell one last time as the curtain drops, and the parents jam into the lobby and fill it with the roar of pointless chitchat. Scotty cries until his brother comes out and joins us. Cartter wants to go home. We don’t let him. Scotty wants to skip school too. He gets dropped off at kindergarten anyway. The big morning is complete, and Danyelle and I get to go home and enjoy five hours without the kids, not socializing with anyone, thankful for the Earth, because without it, we would all die. Also, there would be no life.

War

A throng of traffic moves across the Legare Bridge that spans the Ashley River. Drivers jockey for position, as they spill off the overpass and onto the crosstown, and I elect to stay in the right hand lane and take the narrower downtown streets before rejoining the horde on the massive Ravenel Bridge into Mount Pleasant. Danyelle’s friend is at the house, and I’m playing the hero, having first picked up Scotty on one side of town, and then Cartter on the other. Now, I’m hauling them both home.

Normally, I’d turn the radio off, but today, I let it play, and the kids and I settle into the peaceful drone of the news on NPR. Lackshmi Sing is giving an update of the death toll in Gaza. I wonder if maybe I ought to turn her off, and then I hear Cartter’s strong little voice behind me:

“What are they talking about?”

“War,” I say.

“Where is the war?”

“Gaza.”

“Who are the teams?”

I tell Cartter there aren’t really teams so much as there are armies.

“Who’s winning?”

“Israel.”

“Who do we want to win?”

“Israel.”

“Why aren’t there wars here?”

Turning onto Coming Street, radio time is over. I explain that our country is protected by two oceans and a very powerful military.

“Why don’t people try to come here?”

I try to reiterate the deterrent force of our military and the ocean. Cartter says he understands. When we get home, he shows me pictures in a book that he’s borrowed from the library. They’re pictures of sunken boats and planes on the seafloor. “It’s dangerous to cross the ocean,” he says. I think of white-knuckling my way across the Atlantic the few times that I’ve flown to and from Europe, terrified that if we crashed, we would end up on the bottom of the ocean, and nobody would ever find us. I wonder if my son is doomed to have the same irrational fear now. Damn you, Lackshmi Sing!

Toy Story

A camo croc missing its partner, a rain jacket turned inside out and wadded up, loose construction paper and colored pencils – my living room floor looks like the kids spent all day in fast forward. A pair of bongos tipped on its side next to the keyboard, scattered worksheets brought home from school, playing cards strewn about – the only sign of a slowdown is a little kiosk in the corner made from a big leather ottoman and an upside down Amazon box. A binder of Pokémon cards lies open on top next to a book entitled How to Train Your Pokémon. A sign scotch taped to the front reads, “Welcome to Pokémon Center. We will help you when your Pokémon is sick, acting weird, or any other aquerd problems with your pokémon.”

No more dinosaurs. No more dragons. No more toy cars and trucks. Then I notice him lying alone beside the fireplace – Woody. His limbs are all askew like he was thrown from his horse and shattered all his bones. Two years I dressed up as Woody for the boys on Halloween. Cartter was Woody too. A little plastic toy made in China that my kids projected their souls onto. I half expect him to stand up, pull himself together, and tip his hat to me: “Howdy, partner!” I see Scotty’s face in my mind, smiling at me as he pulls the string on Woody’s back over and over: “Somebody’s poisoned the water hole! . . . Whoa! Easy there, partner! . . . There’s a snake in my boot!”

I tell Danyelle that maybe we should throw away all the plastic toys taking up space in the closet and the toy bin. She says she still catches Scotty playing with them sometimes, pretending that they’re alive, moving them around and putting words in their mouths. I think that sounds nice, and I look forward to getting rid of the toys at the same time.

Putting on my shoes the next day, Woody has moved about 12 feet across the room. He’s lying in front of the window now, all twisted up like before. That night I’m in the den, and I hear Danyelle directing clean up with the boys.

“Where are you gonna put Woody?”

“I don’t want him,” comes a child’s voice.

“Ok, you want me to throw him out?”

“Yeah.”

I stop what I’m doing at my desk. I look over my shoulder to the doorway above the piano where Cartter stood when I played him Randy Newman’s You’ve Got a Friend in Me for the first time.

“You know that song?” I asked him.

“Woody,” he smiled at me.

I call into the kitchen where my wife is negotiating the plastic doll’s disposal. “Are you sure?”

Learning to Read

My five-year-old is wearing his all-red outfit, long pants and a long-sleeved shirt, telling me to “Look!” as I lean against my forearms on the kitchen counter. I put my phone down and straighten up, slowly, unfurling my vertebrae and shifting my spine side to side hoping for the sweet release of a pop. Facing me, Scotty stands with perfect posture, like a little three-and-a-half-foot spring-loaded human arrow. He holds a book up over his face, and the cover matches the red of his shirt almost exactly, so it kind of looks like his head has been replaced by a cartoon monkey face. Where Scotty’s wide eyes and smile had been, there’s now a menacing scowl, its apparent hostility somewhat softened by the title above it printed in large capital letters – GRUMPY MONKEY.

It’s the time of day when I have to make a decision between selfish activities like emails, texts and phone calls vs. sitting in the kitchen going over sight words with Scotty. Today, Scotty’s making it easy. He’s climbing onto the stool across from me with his copy of Grumpy Monkey, opening it up and commencing to read aloud – “One wonderful day Jim Panzee woke to discover that nothing was right. The sun was too bright, the sky was too blue, and the bananas were too sweet,” his little voice confidently rising and falling in all the right places. Fuck sight words. He’s reading an actual book.

I want to believe Scotty’s really reading the words on the page and not just reciting them from memory. If I’ve read Grumpy Monkey to him before, it was years ago, but I’m guessing that it’s one of the books he selects for his mommy when I peel Cartter away for separate bedtime reading. I walk to the other side of the counter and sit next to him, watching as he mostly breezes through the book, occasionally pausing to sound out a word, occasionally substituting a word he expects for the one that’s actually on the page. I read along and observe Scotty as different jungle animals diagnose the grumpy monkey and prescribe techniques to cure his condition. A hippo wants him to swim; a crocodile wants him to take a nap; a vulture wants him to eat old meat. I conclude that Scotty obviously knows the book well, but he’s definitely reading it.

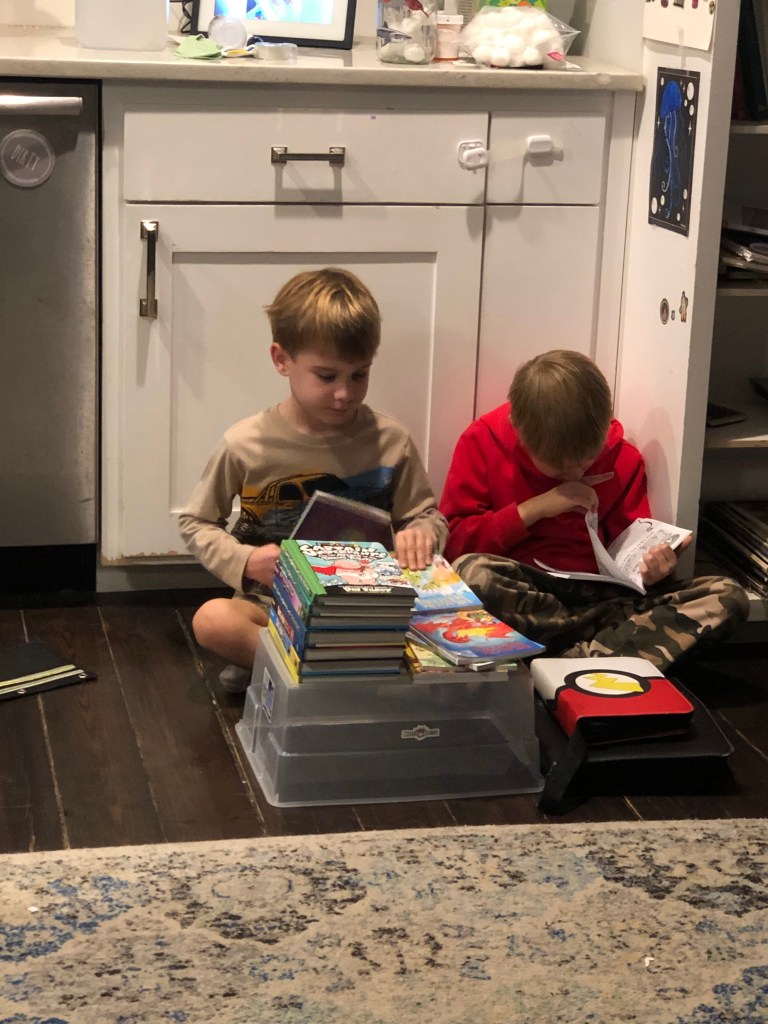

Scotty’s proficiency is a revelation to me. I’ve spent almost no time working with him. Yes, I’ve read to him plenty, but I haven’t had him read to me, and neither has his mother. What we have done is send him to school and practiced sight words with him, and Danyelle has read repetitive books to him ad nauseum and suffered through innumerable pages of Captain Underpants and Cat Kids Comics. Both of us have noticed that for many months Scotty has spent time with his face quietly in a book, but they all have pictures in them, so we thought he was probably just looking at those and kind of pretending to read. Apparently, we were wrong, and now Scotty has decided it’s time to show us just how wrong we were.

Scotty is a big fan of all the praise his reading skills elicit. I tell him I can’t wait to tell his mother, that I’m so proud of him, and that now we have two great readers in the house (the other being his brother). He glances at me between page turns to make sure I’m still paying attention, eyes big and ready to soak in every bit of affirmation I have to offer.

After dinner he wants to read Henry and Mudge and the Long Weekend, a 40-page illustrated snooze fest about a kid and his parents building a castle out of cardboard boxes in their basement after the kid whines about the bad weather. The next day, he selects Mootilda’s Bad Mood, which is basically a knockoff of The Grumpy Monkey that features an ornery bovine and a lot of bad cow puns. It makes sense to me that Scotty is drawn to books about moody animal protagonists. He’s like a mood meteorologist, regularly reporting his emotional state on a scale that ranges from “This is the worst day ever,” to “This is the best day ever,” and that includes various intermediate conditions like “I’m having an ok day,” and “This isn’t a very good day.” Of course he relates with Jim Panzee’s and Mootilda’s moody plights.

Like Grumpy Monkey, Scotty obviously knows the Mootilda story well. Watching as he largely breezes through it, stumbling mostly over the bad cow puns – “This day’s been a cow-tastrophe! . . . Oh my, what a cow-incidence!” – it’s like I have a window into the operations of my child’s mind. I’m reminded of a guy I took some piano lessons from in my twenties, an old guy named Marty, who encouraged me to work on my sight-reading as a way to take my playing to the next level. “Keep reading off the page even after you’ve learned the tune,” he said. Marty got something about the way our brains work that I didn’t. He wouldn’t have been as surprised as I am by Scotty’s ability.

I guess I was always too focused on recall, the idea that I could pound knowledge into my brain and then no longer need the source. I was exceedingly good at memorizing poems for recitation at school, memorizing names and dates for history tests, and memorizing the tunes in my Suzuki piano books for performances. These were valuable skills, because I disliked poetry books and history texts, and I was terrified of sight-reading music.

For at least the first couple of years I took piano lessons, my mom sat next to me on the bench so that I could learn the pieces. At first there were nursery rhymes, “Twinkle Twinkle” and “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” Then it was Mozart and Beethoven. I would learn one measure at a time, playing it over and over until it was all the way in my fingers. Then, I would play the entire line; then two lines; then I’d play from the top down to the last measure I’d been practicing. Playing the piece over and over again once it was committed to memory, pounding it permanently into place, was a pleasurable experience. Tackling a new piece and fumbling with each measure for days on end was a painstaking process. I still remember songs I learned 30 years ago. That’s how much I didn’t want to have to look at the book.

My memory strengthened as the pieces grew more and more difficult, but my sight-reading did not, which was frustrating for Mom. “Why do you keep playing that note?” she erupted in disgust one day. “It’s this one! It’s right there on the page!” I just couldn’t keep it all together, the notes on the page and my fingers on the keys. Translating all those little markings in time and producing the desired sound seemed impossible. I would be amazed when Mom would open her songbook and stare at the page while she played. Her playing was stilted and awkward, and she only played three tunes – “Brian’s Song,” “Moon River,” and “Close to You,” but she was reading them! And pedaling! I was sure I could never do that, and faced with Mom’s frustration that day (and many other days on that bench), I sobbed.

I should have been reading along while I played the simpler pieces that I already knew, like Marty would tell me to do twenty years later, like Mom playing “Brian’s Song,” like Scotty reading Grumpy Monkey. Instead, the only things I read from the page were new pieces, each one the most difficult that I had ever attempted to that point. It wasn’t as good a recipe for increasing sight-reading aptitude as it was for inducing crying episodes. My suffering taught me that I didn’t want to teach my own kid music that way, but sadly, I wasn’t able to extend the lesson to reading English, and I subjected Cartter to a similar experience when he was a first grader.

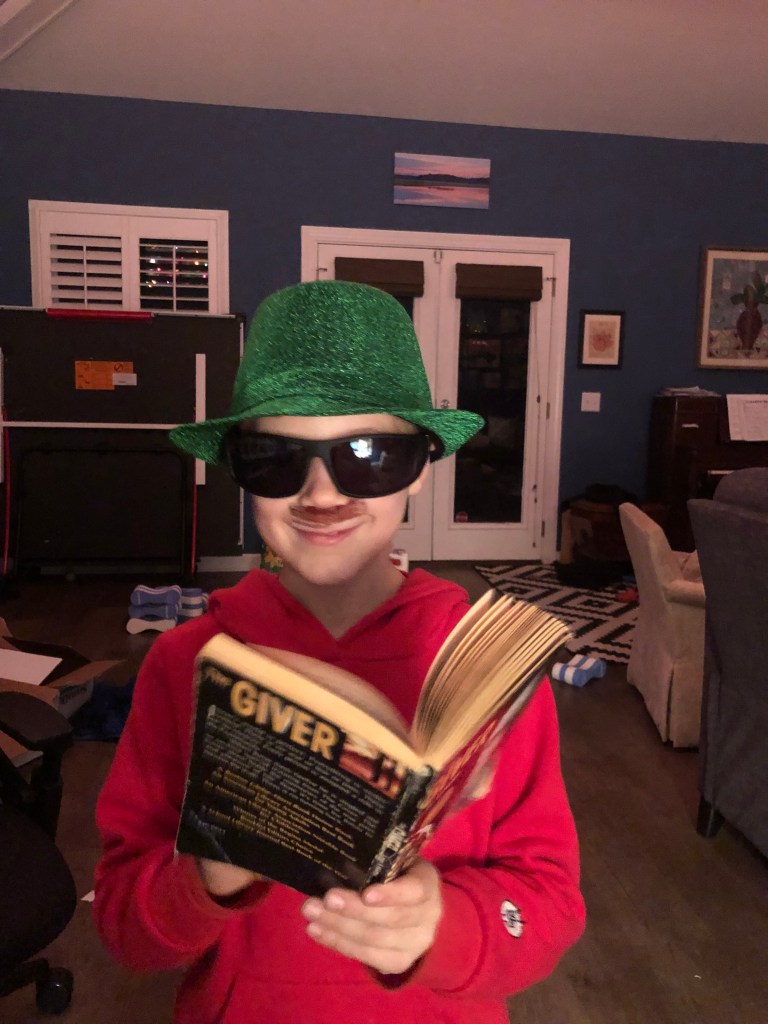

The main thing I remember about watching Cartter’s mind as it learned to read on its own was how it fatigued. His first-grade teacher assigned “read ten” every day for homework, which meant he was supposed to read for ten minutes. I made Cartter read extra. I also picked the books for him. If he brought me The Cat in the Hat, I’d set it aside and make him read one of the chapter books in the Magic Treehouse series. I insisted we read an entire chapter in one sitting. We would take turns reading pages. Cartter watched me do the impossible like my mom playing “Moon River,” and when it was his turn, he would struggle to sound out a third of the words while I held the book, pointing to keep him on track, feeding him words to push the pace. Each page grew more difficult as his ability to focus waned, and when he struggled so mightily through a sentence that it lost all meaning, I would make him go back and read it again, trying to condition his mind’s powers of concentration. It was like learning a new piece measure by measure, line by line, a painstaking process that both of us wanted to end, only when Cartter begged to quit, I wouldn’t let him, and he would cry. I don’t know how much my pushing Cartter helped him vs. how much it hurt him, but, eventually, I let up, and lo and behold, Cartter’s reading skills continued to ramp up really quickly anyway.

Now, with Scotty, I don’t push. He brings me his books and is eager to read them to me. He doesn’t want to stop after ten minutes. He wants to read one after another. After we finish Mootilda, he brings Henry and Mudge and the Big Sleepover. I sit next to him on the couch and hold the book so that I don’t have to twist my neck and spine to see the page. By page 20, my eyelids are heavy, and I’m letting them shut for a split second at a time. I afford Scotty plenty of time to sound out words he gets stuck on before slowly, sleepily feeding them to him. Scotty presses up against me and rests his head on my chest. After he gets stuck on a word, he goes back and reads the whole sentence with proper intonation without prompting from me. “He’s particular about his work,” his kindergarten teacher told us. I wish Scotty could have shown me how easy this was before I put his older brother through the wringer.

After dinner, neither Danyelle or I feel like reading to the kids. Instead, we send them in the back together, and they snuggle up on a beanbag chair. The two of them pick out books, and Cartter reads to his brother – Where the Wild Things Are, and Captain Underpants. We told them ten minutes. They go for thirty before I go into the back and break it up. They smile and whine at me at the same time, “Awwww.” I say goodnight to Scotty last.

“What book are you gonna read me tomorrow?” I ask him.

“I don’t know,” he says. “You’ll just have to find out.”