Dear Elite,

As I accelerate into the intersection at Shelmore Blvd. amid a throng of cars on Hwy. 17 carrying solitary drivers to work, I see my five-year-old’s face finally turn away and look toward his destination. He’s in the truck with his mother, on the way to kindergarten. I’m driving the van with his older brother Cartter in the back seat, heading across town to drop him off at his first day of second grade. For the entirety of the five minutes since we all left the house, the two boys have been craning their necks to look at each other through the window and wave. Now, they’re finally out of each other’s sight, riding off in different directions. “I’m gonna miss him,” comes Cartter’s voice from behind me.

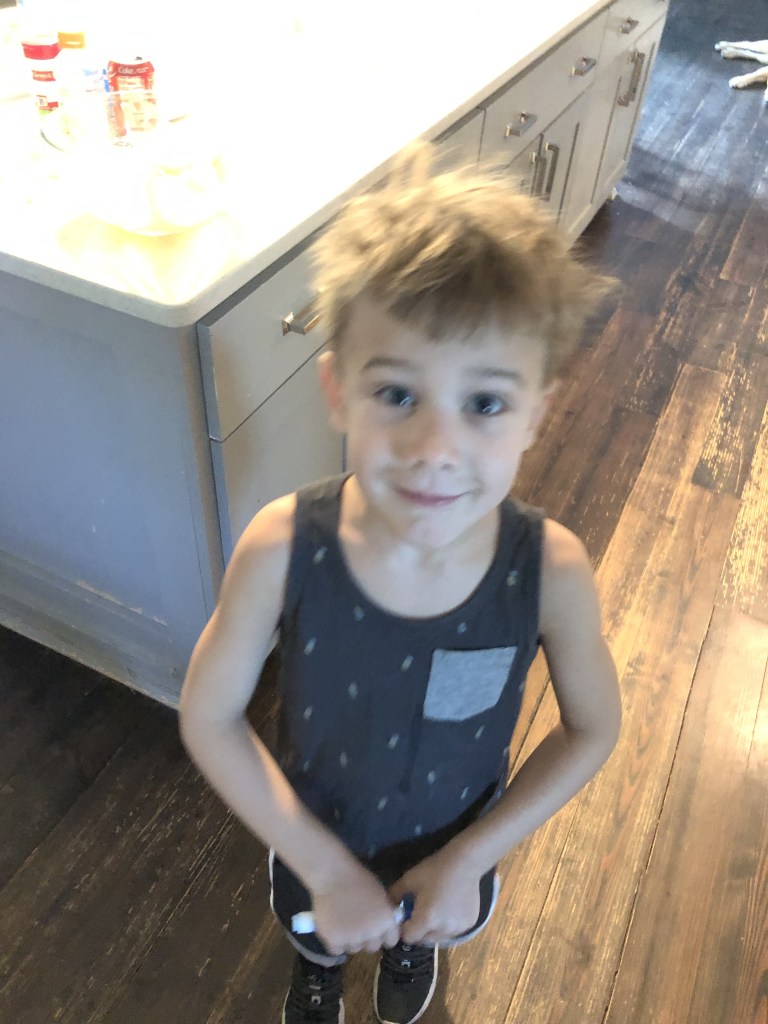

Separation has been scarce during the summer break from school. The boys have spent nearly every waking second together. In the neighborhood they’ve become known by families of a certain age as “the brothers.” On one of the last days of summer, as I approached the community pool, Danyelle and the boys already having spent the better part of the morning there, the 17-year-old lifeguard Jack smiled impishly at me from behind the front desk. He said that the brothers had told him on their way in that Scotty was the king and Cartter was his servant and that they were going to get married. I was already aware of this royal fantasy. Prior to their pool visit, the boys had enacted it by draping a blanket over the dog chair next to the foyer bathroom and using it as Scotty’s throne. I shook my head and asked Jack if they told him they were going to have babies, expressing my concern with how difficult it is to keep them off one another. “They’ll grow out of it,” he said coolly, and then, “Do they fight?”

Oh, they fight. Lately, Cartter’s quickly approaching seventh birthday has been fuel for their inner beasts. Cartter’s been enjoying opening a few presents early over the course of the last week. Scotty has enjoyed it less so. Each new toy (a remote-control spider, a mechanized lizard, some boxing doohickeys) has prompted a test of wills and jockeying for the right to play. After a full day of watching Scotty huff around the house with his brow furrowed and listening to him make dickish comments to his mother, I finally realized what was happening. Following the next fight, I pulled each boy aside for a fatherly lecture. When I told Cartter that I knew his birthday was coming and that he wanted it to be all about him, I was met with a sneering, indignant objection. When I told Scotty that I understood he was jealous, he told me, “I don’t want to talk about this anymore.” There were momentary breakthroughs in each conversation (Cartter’s sneer faded when I told him, “It’s ok,” and Scotty draped himself over my knee, silently acquiescing to a back rub), but both ended with a child eagerly turning his back to me and fleeing the room. Apparently, they’d rather be with each other and fight, than be separated and listen to me.

I’m sure that Jack is right. They won’t always be rolling around on the floor on top of each other, either saying that they’re going to get married or in a screaming argument. They will grow out of it. The problem is that they’ll grow out of other things too, and they’ll do it too quickly. I don’t want to say goodbye to their sweetness, their adorableness, their innocence. I’m exhausted by this second go round with early childhood, but that doesn’t mean I want it to disappear completely. The boys, on the other hand, falsely claim that they want to take an eraser to it. When I catch Scotty humming a tune and put on the Winnie the Pooh soundtrack, Cartter bursts into tears, because it’s for babies. Scotty’s eyes gleam with pleasure at the sing-songy melodies from his earlier years, but if big brother is done with baby stuff, well then so is he. When I put on a James Brown song and tell Scotty that I used to listen to it while I held him in my arms as an infant, he furrows his brow and says, “I hate this song.” I suppose it’s necessary for their little egos that they reject some of the joys of their preschool years in order to smooth the transition into the next phase of their lives. Still, as I see my little Winnie the Pooh lover turn away on the drive to his kindergarten, I wish they wouldn’t. I’m not ready to say goodbye to Winnie again.

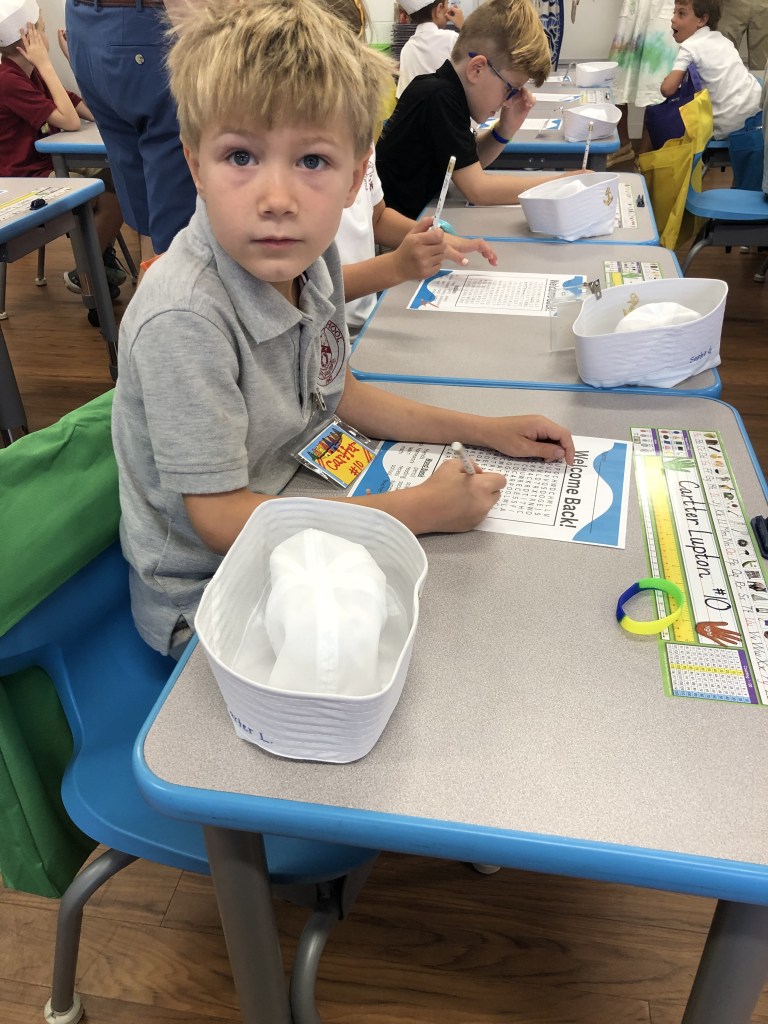

Back in the van heading towards the Ravenel Bridge, I reassure Cartter that he’ll see his brother again in a few hours, expecting him to be nervous about his first day. When we get to his school, though, I’m surprised that he doesn’t really seem very nervous at all. He’s excited, chatty, eager to show me where the second-grade hall is, because he already knows, and I don’t. There’s a mob of parents and kids pouring through the gate and into the breezeway. The buzz of overly friendly smiles and greetings surrounds us. Cartter has moments of pause, but for the most part he seems largely self-assured. We locate his room, and he is glad about being number 10 on the alphabetical list of classmates again this year. He scans the list for names of friends, we squeeze through the doorway and meet his teacher, and Cartter immediately sets about putting his things in his cubby and getting to work on the assignment posted on the board. It feels so unlike the sentimental first grade drop off of a year ago. When I sit on a table next to him and say his name to get him to look up so that I can commemorate the occasion with a photo, the bluntness of his reply, “What?” surprises me and lets me know that I’ve lingered too long.

There’s silence in the house again for part of the day. It hangs in the air so thickly that you could swim in it, a welcome reprieve from the brothers’ nonstopness. Still, the start of the schoolyear is another mile marker in the rearview mirror, a reminder that one day not too long from now we’ll be saying much harder goodbyes and that the perfect closeness of early childhood will feel farther and farther away. During Cartter’s latest push to distance himself from everything baby, he’s been asking a lot of questions: “Daddy, does infinity include all the numbers? . . . Why are dog years so short? . . . What if a baseball game lasted forever? How many endings would that be? . . . What does stitious mean?” The other day as the four of us were in the van rounding the bend into the neighborhood, he asked me, “Why is it called Neverland where Peter Pan lives?” It’s funny; I’d never really thought about it very much before, but the answer came easily – It’s because Peter Pan is a boy forever; he can never grow up; that’s why he has to stay in Neverland. It’s like how Pooh Bear stays in the Hundred Acre Wood and promises to always remember Christopher Robin, even when the little boy turns 100. Neverland is that place way down inside that can’t be changed. It’s the part of you that’s a child forever, the part that always loves Winnie the Pooh. Don’t you forget it, son.