Dear Elite,

There was a time in my life when I thought I was going to be an interpreter. At 24, led by a clueless belief in my Spanish language proficiency that was buoyed by my adult ESL students’ compliments, I found myself in the language lab at the College of Charleston, trying out for the “bilingual legal interpreter” program. I had to wear headphones and listen to a recording of a woman talking while simultaneously repeating into a microphone what she said. When she was speaking English, it wasn’t so bad. When she was speaking Spanish, I felt like a goddam idiot. The Argentinian lady who administered the test was nice about telling me I failed. She referred me to some kind of independent study and said that after six months, I’d be able to pass. Fuck that, am I right, elite? I didn’t spend 4 years in college studying a foreign language so that I could suck at it, and after talking with this Argentinian lady and trying to shadow the woman on the tape, it was clear to me that I was always going to suck at it no matter how hard I worked. Sure, I could get much better, but people like this lady were always going to be far superior to me in their bilingual skill. Again, fuck that. We elite are meant to be the best at what we do. We’re meant to lead. I knew I was an elite communicator. I just needed to find my medium, a place where my unique ability to interpret the world around me and distill it into easily relatable, absolute truth wouldn’t be wasted, a place where people could understand the amazing impact that my talent was having on their lives. The time for studying and being a beginner at stuff was done, so I ditched the foreign language crap and turned to a world of whose language I already possessed total mastery: kids’ swimming. Naturally, with no language barrier in the way, I rocketed straight to the top – Head Age Group Coach, much beloved by parents and kids alike, Coach of the Year Award recipient. I quickly became the face of age group swimming in Mount Pleasant. Elite humility aside for a moment, I was plain good at it. I coached hundreds and hundreds, maybe thousands of kids. I remember a mother telling me once that I was going to be so well prepared when I became a father. Before she said it, I already believed that very same thing. Once I heard the words come out of her mouth, though, I grew suspicious of that belief, and rightly so as it turns out. Now the father and swim coach of two boys, I sometimes feel like I’m back in the language lab at the College of Charleston, attempting to decipher some foreign jibber jabber, feeling like an idiot as I try, and fail, to follow along.

When it comes to communicating with the kids (and when I say the kids, I mean my kids), the trouble is that opposite day rules apply. Yes, I’ve recently discovered that opposite day is still a thing. Of course it is! My six-year-old has been telling me it’s opposite day a lot lately, which is great. He’s delighted about it. It makes it a little more difficult for me, though, as his dad, because as we all know, the tricky thing about opposite day is that if someone says it’s opposite day, doesn’t that mean it’s actually not opposite day? That’s the crux of opposite day rules, and since it’s opposite day (or not opposite day, whichever you prefer) pretty much all the time, nearly every word that comes out of the kids’ mouths has to pass through a sort of internal parental opposite day decoder. The problem with this mechanism is that just like my skill in shadowing a native Spanish speaker’s speech, it tends to work a good bit slower than real time.

Don’t get me wrong. My elite decoder is fucking tops, and a good portion of the time, the speed with which it operates makes me as close to fluent in opposite day kid bullshit as any adult can be. Like when Danyelle makes chicken and rice in the crock pot, and I hear whimpering complaints of fullness and stomach pain quietly emanating from the dining room as I prepare my own plate in the kitchen. It goes like this: First, I recognize the context – a few minutes ago, the kids were rolling around in the living room fighting, periodically taking breaks to proclaim that they were hungry and to ask when dinner would be ready; this chicken and rice, a dish Danyelle has never made before (she attempted the day prior and failed because she forgot to turn the crock pot on – sub alert), doesn’t look very good; and the weak refrain coming from the dining room is all too familiar: “I’m full,” “My stomach hurts.” Ok, I understand where we are. Second, I set my decoder accordingly. In this case, the setting is one of my all time favorites: hungry kids picking at diligently prepared food and whining during mealtime (notice the specificity). That’s really all I have to do. Once I set the decoder, it handles the rest. The kids’ bullshit passes through the bullshit filter, and the decoder transmits one of two signals, either (1) “this is bullshit,” or (2) “This actually isn’t bullshit.” Pretty great, right? But wait, there’s more. When you use the device properly, i.e. turn it to the proper setting, it transmits the bullshit signal directly to the Great Man, who is then able to infer and relay actual meaning, in this case: “I’m hungry, but this isn’t what I want. I want you to make me something else.” Amazing. The end result? Irritation and peanut butter sandwiches.

In the world of parenting, the kids whining at dinner time when presented with an unfamiliar meal is like the woman speaking English on the tape in the language lab – easily interpreted. Setting the decoder is almost automatic. It takes hardly any effort. Unfortunately, the decoder has infinite other settings, of which the majority are hardly, if ever used. Trying to find one of those lesser used settings while apparent bullshit is swirling all around in the outside world will make you feel like an idiot trying to repeat some woman on a tape as she speaks Spanish at 100 miles per hour. Try finding the “crying at the dinner table after my brother launched a vacuum extension at my face” setting for instance. I’ve already detailed in previous elite pages how that one took me a while. Notice how it bears a striking resemblance to the hungry kids whining at mealtime setting detailed above. They seem close. They might even be right next to each other on the dial for all I know, but that doesn’t mean they’re at all related. Swap one for the other, and the decoder will signal bullshit when your kid’s tooth is actually chipped in half. Alas, the old man’s axiom rears its ugly head again. When you think you’ve got something figured out, trouble’s about to find you. Operate the decoder with a false sense of assuredness, and you’ll end up in Opposite Day Hell, frustrated with your kid’s tears, seeking refuge in the next room so as not to fuck up any worse, wondering where the hell the Great Man went (he doesn’t respond to improperly calibrated decoders’ signals). And you thought feeling stupid in the language lab was bad. Obviously, this extreme sensitivity of the decoder to its setting is problematic. It seems obvious that elite parents like us deserve better. We’ve put in the work. We’re paying attention. Our decoders should fucking work. What’s more, they should work even better when we’re feeling particularly self-assured. Like when you’re the coach of the year with decades of experience in the sport, and your kid is on your team, that fucker should be pointing true north all the damn time, not plunging you into opposite day hell. I set the thing right! I know what I’m doing! I’m an expert at this for crying out loud! Why is he crying?

Yes, based on the results I’ve achieved thus far in the kids’ summer league swim season, it would seem that as regards preparation for real world opposite day fluency, my elite experience as a coach was a lot like my years of foreign language study in college: academic. My inability to interpret our older boy’s bullshit has been particularly baffling. I expect the springtime baby to be uncooperative at times, and he certainly has been, but Cartter is a model student – “I wish I could have a room full of Cartters,” his teacher says. “All the other teachers agree.” Moreover, this is actually his second year on the team with me; he crushed it last year as a 5-year-old; now, he’s the fastest 5-6 year-old on the team, hell, maybe in the whole league; so when I get called over by the 20-year-old male assistant to check in on Cartter behind the blocks at our first meet of the season and find him crying and on the verge of hysterics, I can’t help but feel a little disappointed. Ugh, I’m busy, son. Just swim your lap like a good boy. I thought watching you compete was going to be the best part of this damn thing. I don’t want to fiddle with the decoder right now.

“It’s too cold,” he whines at me, face squished into crying position, mirrored goggle lenses hiding his tears, nervous little hands tugging at the drawstring hanging from the top of his jammer suit that’s hiked up Urkel-style near his belly button. Set decoder to scared little kid struggling with zero body fat, cold water, and performance anxiety at crowded summer league swim meet.

“But, Cartter,” I protest. “You were just in the water during warm-ups, and you said it was warm.”

“But that was bullshit,” he cries back at me. No, not really. I wish. At least that would have been funny. Instead, he stuck with some variation of “It’s too cold” for the duration of our 20-second conversation, except for when he threw in a “my stomach hurts,” which started the needle on my decoder spinning out of control. At a loss, I got out of there as quick as I could, leaving my panicked son in the care of another 20-year-old assistant, this one a female, who was very close to his face and loudly encouraging him as I walked away. Less than a minute after I fled the scene, the race started, and I watched from the side, as my star 6-year-old fucked it all up. He gave up 3-4 seconds on the start, terrified to jump in at first, then stunned and slow to get moving when he hit the water. Then he gave up another 2-3 seconds on the finish just kind of floating a few feet from the wall before putting his hand on it. It was good enough to win the heat. He got third out of 20 or so in the event. He should’ve easily finished first, though. It sucked watching him not do his best. I rolled my eyes at the start and the slow motion first 12.5 yards. Then, my excitement grew as he overtook the rest of the heat in the middle of the pool. Oh, Science, let him win! Then maybe he’ll feel good and not act like this again! As he floated near the wall at the finish, I was gripped by a frustrated parental need for validation, and I cried out, “Touch the wall!” like a sports fan yelling at the TV. One of the friendlier dads was standing next to me.

“Is that your kid?” he joked. “I couldn’t tell.”

It’s been over a week, and I’ve been fiddling with the decoder ever since. I’d like to believe that Cartter’s complaints about the cold water are actually not bullshit. The water is, in fact, cold, and he no doubt doesn’t like that. I can see him shiver. He clearly prefers to sit down and ease himself into the water vs. plunging into it at the sound of the starter horn. If his troubles really are about temperature, I’d be largely free of responsibility. After all, I don’t control the weather. I do, however, control my child’s presence at the pool and my role as the coach of his swim team, so if complaints about cold water are actually just a front pitifully designed to mask fear of failure and a deep-seated insecurity about the certainty of his parents’ love for him, well then I’d be no better than my own parents, which is wholly unacceptable. The body language I’m seeing at practice leads me to want to call “not bullshit. He’s actually just cold,” but when I hear from his mother that some nervous behavior was starting to show up before this week’s home meet, an eventual rain out that robbed me of a chance at superstar coach dad redemption, I start to worry. I don’t want my kid dealing with the anxiety that caused me to throw up for years at year round swim meets, and I really don’t want to be the reason for it. For the moment all I can do is guess that probably the cold, my son’s nature, and his perception of my expectations are all mixing together to form a kind of bullshit creole that the decoder is useless to interpret. See, the opposite day decoder works best when the perpetrator of bullshit knows what they’re doing, when they’re willfully trying to manipulate you in order to avoid getting in trouble or to get what they want, when the bullshit equals something simple like I want you to make me something else to eat. When your little opposite day creature doesn’t know what they’re doing on the other hand, i.e. when they’re unaware of whether or not they’re spewing bullshit, when their emotions are being steered by that shadowy inner voice imperceptibly whispering they’re going to stop loving you, I’m sorry to say that the decoder is fucking worthless. The good news is that in these instances, what’s bullshit and what isn’t doesn’t really matter. The bigger issue is that your dumbass kid has scared himself by acting like it’s opposite day all the time. It’s time to set aside the decoder, and remind the little fibber that you’re not lying to him when you say “I love you.”

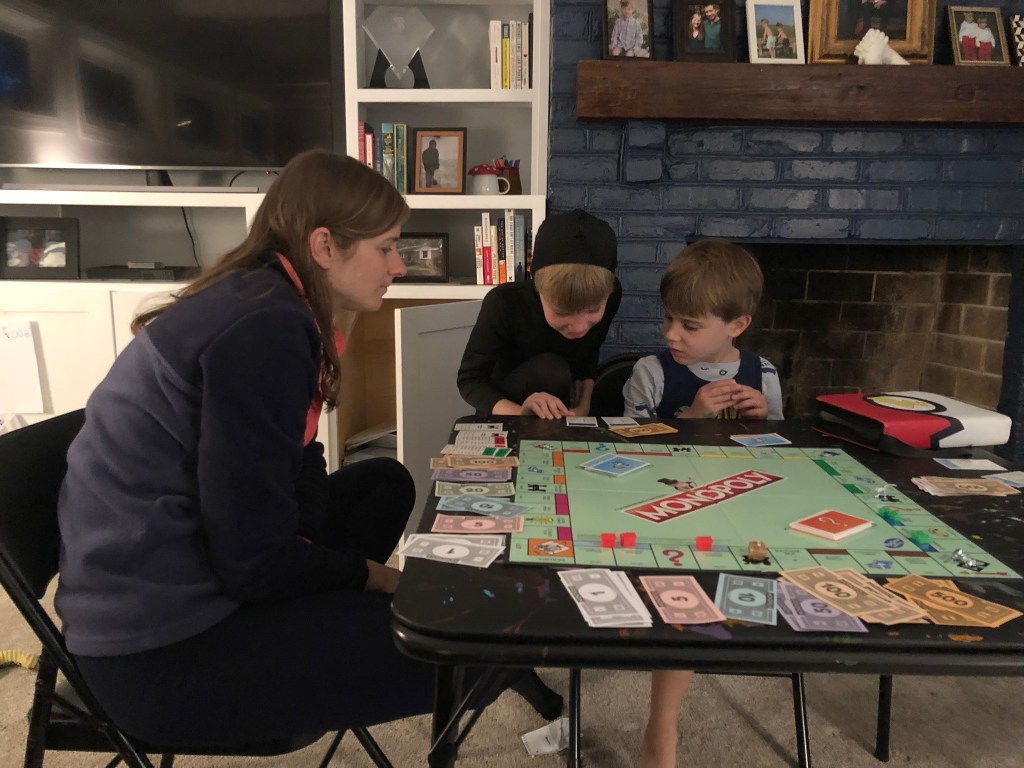

I finally put my decoder down last night. The week following Cartter’s shitty swim included an extra large serving of dumbassery from a particularly moronic pool acquaintance. I’ll just say it’s been distracting. Then there was the stormed out meet, which was basically a total fiasco. After presiding over a 45-minute delay, a visiting team with stomach bug puking on deck twice, and exactly zero heats, I lost my voice, cancelled our plans to visit friends at their beach house over the weekend, and developed a sinus infection. As all this transpired, I pondered decoder settings and possible meanings of my child’s (and my own) behavior in the back of my mind. Am I fucking up his chances at enjoying swimming? Why am I doing this shit anyway? Relief finally came in the form of an evening walk with the family, Cartter donning a Venom onesie that fully masks his face. The boy appears to have some athletic gifts: he’s picking up basketball, and I already detailed his superiority in the pool; but at his core, he may be something of a nerd. The other day he built this robotic arm gizmo with his mother. It was very involved. He’s getting really into Pokémon cards. He likes legos and playing chess with his daddy. He wants to play monopoly for hours on end. You can make of this what you will, but I don’t think I could love my little nerdy boy any more than I do, and after watching him walk the neighborhood in his nerdy little Venom costume, I was ready to stop trying to be the smartest opposite day decoder operator, and cut straight through the bullshit. After successfully ushering him to the shower in preparation for bedtime, I stuck my head around the curtain to check on him. He was standing there with his hands up in front of his chest, catching the water and letting it pour down the front of his skinny little body, his eyes downcast watching the little rivulets pour off of him and slip down the drain, unworried, at home, the exact opposite of the Cartter who cried behind the blocks 8 days prior.

“I love you,” I said.

He sighed the tiniest bit when he answered. It was like the last bit of something gnawing his insides just left him; like he knew the decoder was put away in storage, and he didn’t care to test it; like he could finally relax. “Me too,” he said. That’s right, my boy. Don’t be scared. There’s no such thing as opposite day.